The Birth of the Selfie

by Tom Miller

As 19th century mansions along West 72nd Street made way for 20th century apartment buildings in the post-World War I years, Milton P. Silverman formed the 316 West 72nd Street Corporation around 1923 specifically to replace the four high-stooped private homes at 322 through 328 with a modern apartment building. Brothers George and Edward Blum, partners in the architectural firm of Blum & Blum, were given the commission to design the structure.

Completed in 1924, its prim Colonial Revival façade was highlighted with jazzy Art Deco touches—like the two-story wave crest frame around the entrance. Above the two-story limestone base were 13 floors of dark red brick, the diapering of which formed a tapestry of diamond shapes when viewed from a distance. Potential residents could choose from suites of four to six rooms, with as many as three bathrooms.

One of the initial tenants was in the newspapers—and jail—shortly after moving in. On May 29, 1926, the Daily News reported, “When night broods over New York, romance steals into the very soulful soul of Steven Samuel Henle, 26, of 322 West 72d st.” The article said he “flings care aside, dons evening clothes, swings a silver-tipped stick and sallies out to find what diversion, if any, the metropolis can provide.”

The previous evening Henle had gone out in search of love. The article said, “Now, romance means different things to different persons…For instance, some of us get a big kick out of moonlight, blonde hair and [the] scent of lilacs…But not Mr. Henle. He likes policemen.” At the 50th Street subway station, Henle attempted to kiss Special Officer Downey. As the policeman attempted to dissuade his admirer, a “curious crowd collected.” According to the newspaper, Henle refused to be rebuffed. “Ah, but I know we’re soulmates. Please kiss me.”

Officer Downey had had enough. “Not in public,” he said, “The station house is a nicer place.” And so, the pair went to the stationhouse, and then to the West Side Court where the overly amorous Henle was given a five-day jail sentence.

Officer Downey had had enough. “Not in public,” he said, “The station house is a nicer place.”

And so, the pair went to the stationhouse…

Living in the building at the time were Nathan Scharlin and his wife. Nathan’s brother, Abraham, and his wife came for a visit in the spring of 1927. Abraham was a well-to-do real estate operator in Chicago. It seems that, in fact, Abraham Scharlin was trying to hide from the Chicago mob. But, if so, it did not work.

On April 28 Scharlin received a telephone call from another real estate man, James H. Taylor, who asked him to meet him at 72nd Street and Broadway. What Scharlin could not have known was that four men had guns pointed at Taylor. When Abraham Scharlin arrived at the corner spot, “other members of the gang pounded on him and bundled him into an automobile,” reported The New York Sun.

Scharlin and Taylor were blindfolded and taken to a house in Brooklyn where six or seven Chicago mobsters held them for over a week. They were headed by David Berman, “known as Dave the Jew, said to be a notorious Chicago bad man,” according to The New York Sun. According to the prisoners, “Berman had been rough once or twice, slapping them in the face and cursing at them, but for the most part their captors behaved well.”

It ended on May 5 with a shoot-out that left one kidnapper Joseph Marcus dead, two gangsters arrested, and “a dozen detectives on the trail of the remaining four,” according to police. Officials said they believed they had “cleaned up the Scharlin-Taylor kidnapping case and smashed one of the most dangerous gangs that has operated in New York since the Whittemore gang was captured.”

A reporter who went to Nathan Scharlin’s apartment for a statement was told simply that Abraham and his wife “had left at 6 a.m. with a suitcase.” Four days later, with four of the murderous mobsters still on the loose, The New York Times explained, “On the advice of the detectives, Scharlin and Taylor left their homes and took up temporary hotel quarters, known only to the police.”

Anatol M. Josepho’s story was no less intriguing—albeit less life-threatening. Born in Siberia, he had studied in Prague, and, following World War I had gone to Shanghai. It was there that the engineer-inventor developed an idea for a coin-operated photography machine. Now living in New York City, he developed his idea into the Photomaton, described by the New York Evening Post as “the quarter-in-the-slot picture machine.”

It was the forerunner of the popular photo booth found in carnivals and dime stores across the country for decades. He opened his Photomaton Studio on Broadway near Times Square in September 1925. The New York Times wrote, “Almost since the studio was opened last September crowds have stood in line to put the quarter in the machine and take a strip of eight sepia photos of themselves.” It was the birth of the selfie.

The New York Evening Post said on June 14, 1928, “while still a struggling inventor, [Josepho] married Miss Hannah Kelhmann, a New York girl. They live at 322 West Seventy-second Street.” Hannah was, in fact, silent film actress Hannah-Belle Kelhmann.

Josepho had come a long way at the time of the article. A year earlier Henry Morgenthau, the former Ambassador to Turkey, had purchased the rights for the Photomaton for $1 million—about 15 times that much in today’s money. Now, the 33-year-old waxed philosophic about his windfall. “A man can be just as happy with a few dollars as with a million. The size of your bank account doesn’t mean anything.” What it did mean, he admitted, was that he was able “to work unhampered on several new inventions.” He and Hannah-Belle moved to California later in 1928.

Now living in New York City, he developed his idea into the Photomaton, described by the New York Evening Post as “the quarter-in-the-slot picture machine.”

At mid-century Joseph Siegel, president of the Trade Binding Co., a bookbinding firm, lived in the building. His employees walked off the job around October 4. Labor disputes at the time often involved violence, but normally it was confined to picket lines and protests. But on the night of October 10, it came much closer to home for Siegel, literally. In the years before visitors were stopped at the desk of apartment buildings, strangers were free to enter at will. That evening the doorbell to the Siegels’ 14th floor apartment rang. When Siegel opened it, three men rushed in and brutally beat him. He was unable to identify any of his assailants.

A fascinating resident was Dr. Anna Keegman Daniels. An obstetrician and gynecologist, and author, she was born on June 10, 1893 in Kiev, the Ukraine. She was a founding fellow of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and served as adjunct attending gynecologist at the City House of Detention for Women. She served as medical director of the Planned Parenthood Associate for the South Shore of Long Island and was president of Voluntary Sterilization.

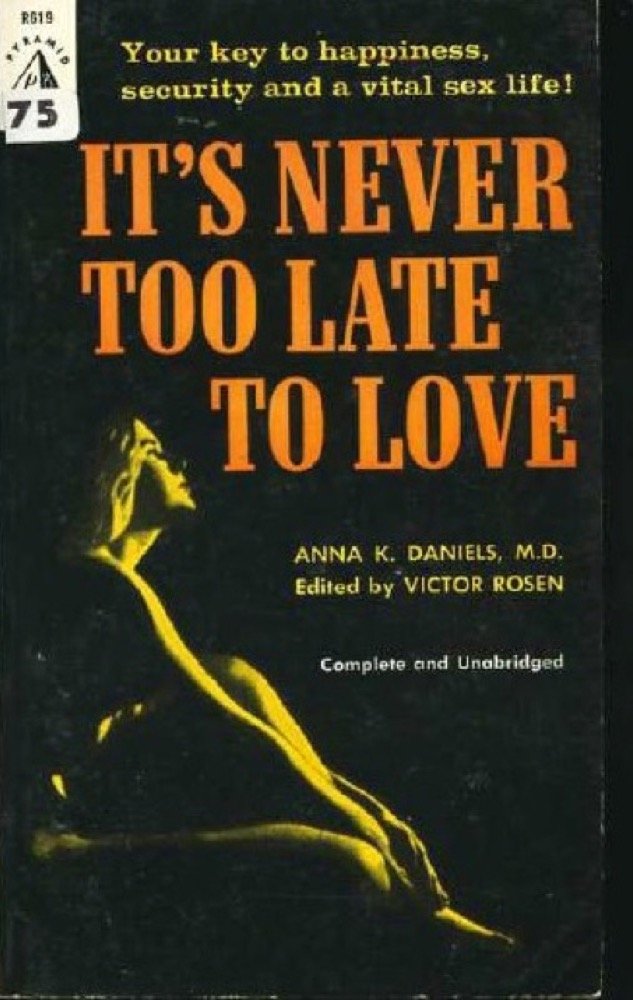

Her books included The Mature Woman and It’s Never Too Late to Love. Among Dr. Daniels’s many memberships were the American Association of Marriage Counselors, the Society for the Scientific Study of Sex, and the Human Betterment Association. She was still living here on March 22, 1970 when she died at the age of 76 at Beth Israel Hospital.

The building got its 60 seconds of fame in 1996 when Fox Sports filmed a promotional spot announcing its National Hockey League telecasts. It replicated the opening sequence of the television series “The Odd Couple,” using hockey greats Wayne Gretzky (in the Felix Unger role) and Mark Messier (as Oscar Madison). The promo caught the two walking out of 322 West 72nd Street and reenacting the famous scene of Madison’s dropping a cigar to the sidewalk and Unger plucking it up on the tip of his umbrella.

Blum & Blum’s staid 1924 building is little changed–its Jazz Age Art Deco details still quietly co-existing with the staider Colonial Revival façade after nearly a century

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT