Strategic for Guided Missiles

by Tom Miller

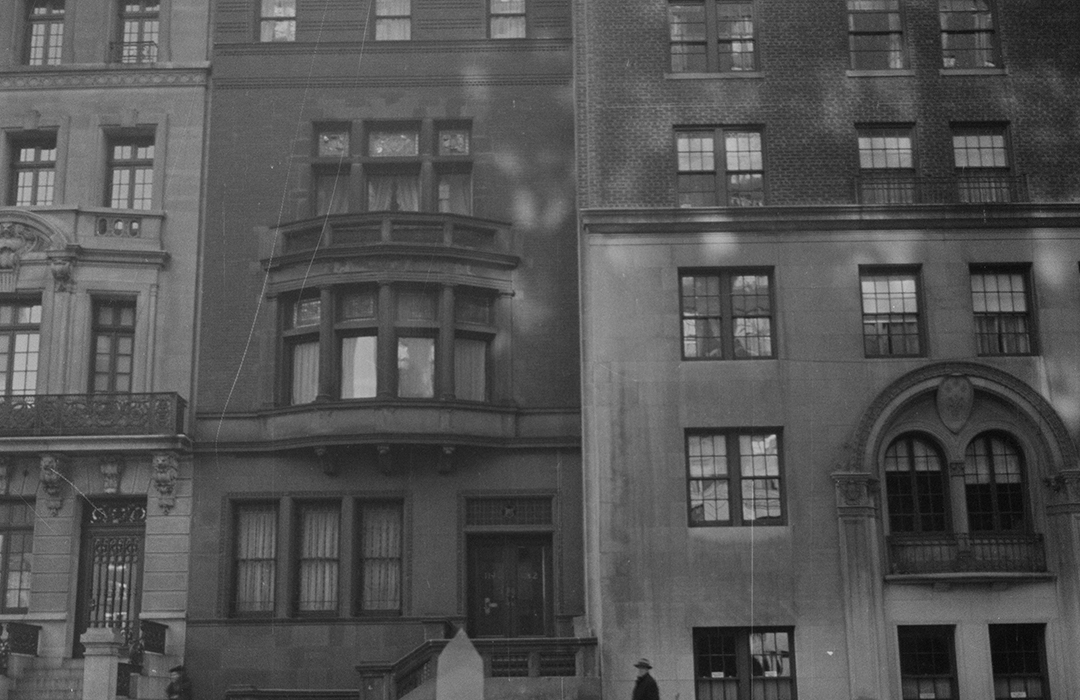

In 1887, John H. Duncan designed an elegant, 25-foot-wide residence at 32 West 72nd Street, just west of Central Park. It became home to Ignatz Boskowitz, president of the Mechanics’ and Traders’ Bank, and his family. He and his wife Carrie had five children, Jesse J., Florence, Irma B., Irene M. and Bella A.

The first of the children to marry was Irene, whose marriage to Louis Demuth took place in the 72nd Street home on the evening of May 9, 1895. Her sister, Bella, would soon marry Joseph H. Sulzbacher—a union that would eventually result in drama, intrigue, and irreparable rifts among the family.

But in the meantime, Boskowitz had another battle to fight. When his house was erected in 1887, it overstepped the property lines to the west by six inches. Now, in the summer of 1896, the prolific real estate development firm of Terence Farley’s Sons was erecting a residence on the plot next door at 34 West 72nd Street. The six inches became a problem.

On July 25, the New York Herald entitled an article “This Stoop to Conquer” and reported “a few inches of the rail of the red stone stoop in front of the house of Ignatz Boskowitz, at No. 32 West Seventy-second street, has been hewn away, and the owner feels the loss keenly.” Boskowitz was so enraged at coming home to find a workman chopping away at his stoop that he had him arrested. The New York Herald went on to say, “he vows that he will send any man to prison who dares to make an onslaught on any more of his property.”

In a letter to Jesse he said, “If we do not return this winter, I expect you to come out next summer if all is well.” Carrie would return, but Ignatz died in Europe shortly after arriving.

The standoff ended up in court with Boskowitz and the sliver of his stoop losing. On July 31, The Sun reported “Justice Andrews says that he believes the plaintiff knew of the encroachment of the stoop when he bought the property; [and] that he is trying to maintain a small portion of his stoop on the property of the defendant.”

Upon Bella’s marriage to Joseph H. Sulzbacher, Boskowitz formed the brokerage firm of Sulzbacher & Co. with the two as partners. The firm failed in 1905 but the extremely close personal relationship of Joseph and Bella Sulzbacher with Ignatz and Carrie Boskowitz continued.

Ignatz sold the 72nd Street house to his brother, Adolph, on June 8, 1906 for $100,000—just under $3 million in today’s money. The following month he and Carrie sailed to Germany. In a letter to Jesse he said, “If we do not return this winter, I expect you to come out next summer if all is well.” Carrie would return, but Ignatz died in Europe shortly after arriving. Carrie moved in with Joseph and Bella who, it seems, soon initiated a smear campaign against the other Boskowitz siblings.

On April 3, 1907 Carrie formally disparaged Jesse’s handling of her husband’s estate and asked that Joseph Sulzbacher replace him as administrator. In response, Jesse and his three siblings sent their mother a letter which said in part, “Although it is plainly visible that your attack is inspired by your daughter Bella who has wielded such a singular influence over you for years, still it is incredible that you could lend yourself for such a purpose. With much sorrow we must realize that you have thus chosen to bring the relationship between us to an end.”

Adolph Boskowitz added his own two cents, saying in a letter “Your attempt to cast aspersions upon him is dictated by the malignity of your daughter Bella toward Jesse and your other children.”

Jesse initiated some private detective work into the affairs of his brother-in-law. On December 11, 1907 The New York Times reported that Sulzbacher had been arrested for “erasures and changes” to the books of Suzbacher & Co. which had “affected [Ignatz Boskowitz’s] interest in the business.” He was also indicted for forgery and for offering a $3,000 bribe to Harry L. Wyatt not appear as a witness before the grand jury.

In the meantime, Adolph Boskowitz moved into his brother’s former home. By 1910 the once exclusively residential street was seeing the advance of commerce and apartment buildings. That year, in March, he hired the architectural firm of Rouse & Goldstone to alter the mansion into bachelor apartments—one per floor.

An advertisement for the new apartments touted “four large rooms with bath each. May be occupied by two friends. In exceptionally handsome residence.” Only well-heeled gentlemen could afford to live here. The rent for the parlor floor would be equal to more than $4,300 per month today; the third floor going for about half that amount.

Boskowitz retained one of the apartments for himself. Within only a few years the changing face of West 72nd Street began to test his nerves. He complained to the Public Service Commission on January 17, 1915 about the heavy motor buses. The New York Times said he “has found that the stages run at such speed past his house that they are causing it to vibrate, and that if there is no reduction in their speed or weight his property will be damaged seriously.” He insisted he was not against motor buses, which were “a great convenience to the neighborhood,” but demanded that their weight or speed be regulated.

The New York Times said he “has found that the stages run at such speed past his house that they are causing it to vibrate, and that if there is no reduction in their speed or weight his property will be damaged seriously.”

The house received another make-over in in 1937 by architect Philip Freshman. His renovations resulted in a total of 11 apartments. It was most likely at this time that Ignatz Boskowitz’s stoop, which had caused so many problems in 1896, was removed. A more all-encompassing renovation was completed in 1955 by the architectural firm of Daub & Daub. Any trace of the 19th century façade was stripped off and a blank veneer of beige brick was applied. Interestingly, the front was not pulled forward to the property line, as might have been expected, and the entrance remained below sidewalk level where the former English basement door had been. The architects’ severe mid-century design featured only thin masonry band courses below each floor and modified Chicago style windows.

Among the tenants in 1968 was 35-year-old Belgian electronics technician Pierre M. Stevens. He was arrested on March 14 that year as he attempted to board a flight to Brussels with what authorities said was “false identification.” Stevens had good reason to want to leave the country. He had just dropped off a crate addressed to Belgium at Pier 36 on the East River, declaring the contents as “house hold goods and personal effects.” Stevens placed a Customs value of $750 on the shipment. When Customs officials opened the crate, instead of household goods they found electronic equipment deemed “strategic for guided missiles.” Stevens pleaded guilty to the charges.

No one passing by the yellow brick apartment building today can imagine that somewhere inside are the bones of a magnificent 1887 mansion.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT