Town Topics Tragedy

by Tom Miller

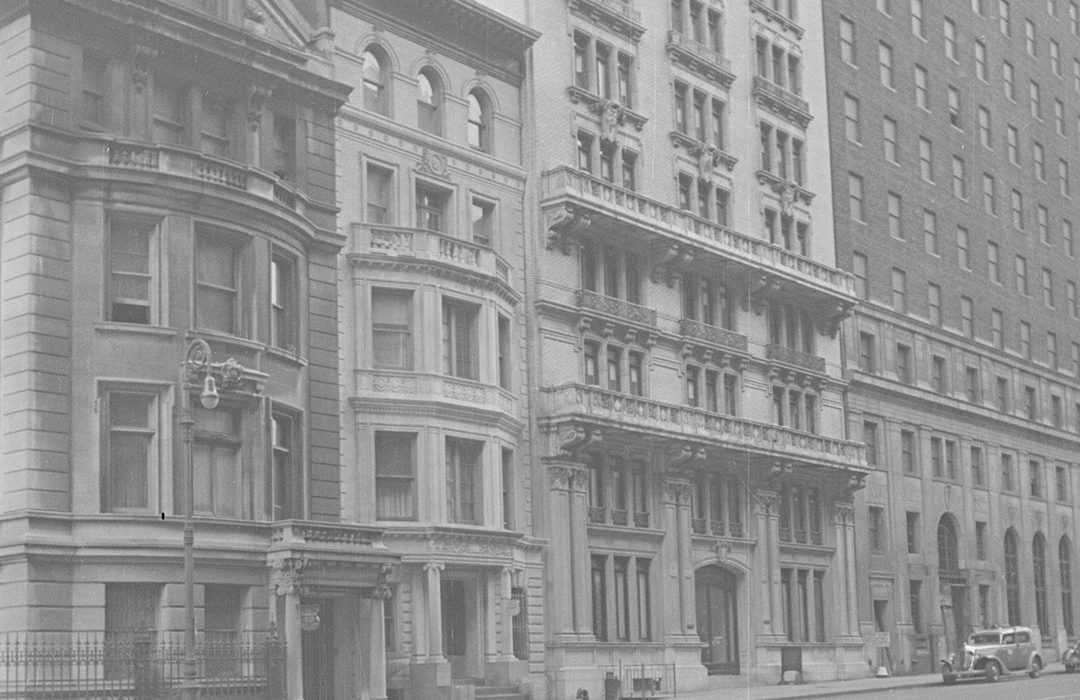

At the turn of the last century, the Upper West Side near Riverside Drive rivaled Fifth and Madison Avenues with its lavish mansions. At 309 West 72nd Street, just around the corner from Riverside Drive, William E. Diller was constructing one more.

Begun in 1899 the house was designed by Gilbert A. Schellenger and was meant to hold its own among the speculative residences aimed at the very rich. As construction continued in 1900, William D’Alton Mann added to his fortune and questionable business practices by founding The Smart Set magazine.

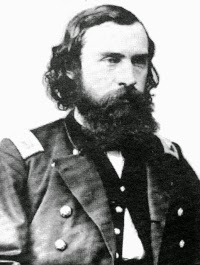

The widely-talented Mann was born in Sandusky, Ohio on September 27, 1839. Educated as a civil engineer, he distinguished himself in the Civil War not only for organizing the First Michigan Cavalry and the Seventh Michigan Cavalry; but for inventing “valuable accoutrements for troops” as described later by Who’s Who in New York City and State.

Following the war, he settled in Mobile, Alabama where he manufactured cottonseed oil and ran a direly needed railroad construction operation. It was here that he first dabbled in journalism as the proprietor of the Mobile Register.

William D’Alton Mann’s business sense and inventiveness would have continued to garner him a significant fortune had he not continued in publishing. In January 1872 he patented the “boudoir car” and spent a decade in Europe marketing it there. Upon his return in 1883, he settled in New York City, sold his Mann Boudoir Car Co. to the Pullman Car Company, and in 1891 became editor and owner of Town Topics.

In the Gilded Age of the 1890s when the wives of New York’s millionaires scratched their way to social significance, every scandalous word—true or not—printed in Town Topics was read with delicious zeal.

It was the beginning of the end of Mann’s respectability and reputation among society’s highest echelons. The high-end appearing newspaper offered news, literature, sports and business advice as a clever disguise. Its subscribers were, in fact, interested only in the social columns, which were in fact a gossip sheet.

In the Gilded Age of the 1890s when the wives of New York’s millionaires scratched their way to social significance, every scandalous word—true or not—printed in Town Topics was read with delicious zeal. Those at the highest levels trembled in fear of being mentioned in Mann’s scathing columns. He rarely printed names; but gave tantalizing and obvious clues like “though unfortunately a woman, is not an American, but a specimen of British aristocracy.”

Millionaires with names like Vanderbilt, Gould, Morgan and Whitney met with Mann in the days just before Town Topics went to press—normally at Delmonico’s—and made deals to ensure discretion. The amounts paid to bribe Mann were incredible; William K. Vanderbilt paying $25,000 (in the neighborhood of $715,000 today) and Thomas Fortune Ryan, for instance, paying $10,000.

Pleased with his successful newspaper, Mann founded The Smart Set in 1900. By now, he had organized a network of informants including household servants, hotel employees, telegraph operators, tailors and seamstresses who eagerly exchanged juicy overheard information for cash. Even socialites, realizing Town Topics and The Smart Set were efficient means to achieve vengeance, sold secrets.

Late in 1901, William E. Diller’s speculative mansion at No. 309 West 72nd Street was completed. Schellenger’s five-story Renaissance Revival design featured a two-story, three-sided bay at the second and third floors, supported by a columned entrance portico. Clad in Indiana limestone and buff-colored brick, it was intended for a family of wealth, refinement and decorum. Instead, it would get William and his bride.

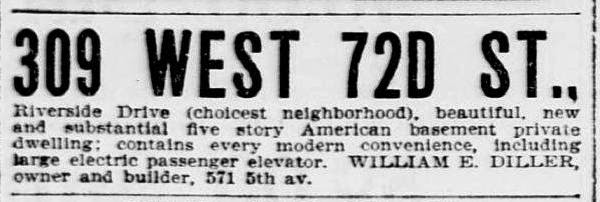

William D’Alton Mann had remarried not long before the completion of the house to Sophia (called Sophie) Hartog. It was possibly William Diller’s advertisement in the New-York Tribune on April 28, 1902 that caught Mann’s eye. Diller marketed the house as in the choicest neighborhood with “every modern convenience, including large electric passenger elevator.”

Moving in with the couple was Mann’s daughter, Emma Mann Wray. Not long afterward, cracks began to appear in the foundation of Mann’s scandal and extortion-based empire. In 1903, he was engaged in a lengthy libel suit. But things deteriorated further after he scandalized Alice Roosevelt the following year. Mann’s newspaper said she wore “costly lingerie” for the “edification of men” and was guilty of “indulging freely in stimulants.” The article said rumors around Newport suggested that she and a “certain multi-millionaire” engaged in “certain doings that gentle people are not supposed to discuss.”

Collier’s Weekly vehemently attacked Mann’s sleazy operations. And when Mann announced in 1904 that he intended to publish Fads and Fancies, a book-form compilation of Town Topics, he went too far. Mann offered the book at pre-publication subscription to high society folks. On July 15, 1905 The New York Times reported “From Louis H. Orr of the firm which has printed the work to be published by the Town Topics Publishing Company under the title of ‘Fads and Fancies,’ it was learned yesterday that $1,500 was merely the minimum price set for that work, and that a large number of copies had been subscribed for at sums several times larger.”

The first person to purchase a subscription had been John Jacob Astor, on July 30, 1904, quickly followed by Mrs. Howard Gould and Clarence Mackay. By the time of The Times article, well-known names as far-flung as Frank Tilford, Stanford White, Florenz Ziegfield, Isaac Guggenheim and Ogden Amour, the Chicago meat packing tycoon, had paid up.But broker Edwin M. Post would not be intimidated. He had Mann’s solicitor, Charles H. Ahle, arrested on charges of attempted extortion.

Mann attempted to deflect the controversy. When a reporter from The Evening Telegram visited him at his West 72nd Street mansion on Monday, July 24, 1905, the publisher insisted “Fads and Fancies is to be a specimen of the highest art in printing, bookbinding, engraving and everything that pertains to the printers’ art, as a biography of the lives of one hundred of the greatest men who by their achievements are destined to mark the beginning of the twentieth century.”

He vociferously said “It is nobody’s business who subscribes to ‘Fads and Fancies.’ This thing is absolutely legitimate. There is absolutely no blackmailing, or anything of the kind connected with it, and I defy anyone to prove it.”

The courts decided to do just that. On December 29, 1905 The Times reported “The methods used in obtaining subscriptions to ‘Fads and Fancies’ were gone into at length yesterday at the hearing before Magistrate Whitman, in the West Side Court.” Among those who appeared as witnesses were Mark Twain, and Peter Cooper Hewitt.

Things only got worse about three weeks later when William d’Alton Mann was arrested for perjury. His daughter, Emma Mann Wray, bailed him out by offering as collateral the property at 810-828 West 38th Street, where Mann was building his new publishing building. The charges against him said, in part, “That the testimony so given by Mann was false and untrue, and that Mann willfully, knowingly, corruptly, and feloniously testified falsely.”

On July 15, 1905 The New York Times reported “From Louis H. Orr of the firm which has printed the work to be published by the Town Topics Publishing Company under the title of ‘Fads and Fancies,’ it was learned yesterday that $1,500 was merely the minimum price set for that work, and that a large number of copies had been subscribed for at sums several times larger.”

Years of litigation resulted in murmurs that Mann would walk away from his publishing firm. On February 24, 1912 The New York Times reported “It was rumored yesterday that Col. William D. Mann was about to sell Town Topics and retire from newspaper work. When he was seen last night at his house, 309 West Seventy-second Street, Col. Mann said:

‘I have been twenty-one years at the post of duty, and I hope I shall continue there for as many more. I do not know where the rumor originated, but you can say positively that I have no intention of retiring or selling Town Topics.’”

Before 1920, William Mann left 72nd Street. On April 20 that year The New York Times mentioned “Mr. Mann is now living on Madison Avenue.” He had just purchased a ten-acre estate in Morristown, New Jersey and intended to make “extensive repairs” before moving in. Four weeks later, on May 17, he was dead.

309 West 72nd Street was for a time home to Miss Lucile Peterson. Then in 1929 it was converted to a doctor’s office and “housekeeping apartment” on the ground floor and non-housekeeping apartments above. The following year Beatrice Taylor leased the house for 21 years, with the intentions of operating it as “a furnished apartment house.”

The tenant list in those Depression years included some not-so-respectable characters. On April 29, 1931, Lt. Walter Culhane of the New York City Police Department arrested Joseph Dinan, a Bronx gangster. The New York Times reported on June 26 that a month afterward Culhane arrested “a confederate at 309 West Seventy-second Street.”

The humiliation of the once-grand home continued when in 1937 architect Roy Clinton Morris converted the interiors to 19 furnished rooms.

The building was owned by Samuel H. Hofstadter, Jr. in 1958 when in reaction to recent deaths the city instituted new fire laws. They required owners of multi-family buildings to install sprinkler systems. Hofstadter waged a legal battle, suing the city and calling the law unconstitutional. The courts did not agree and on March 28 that year he lost what newspapers deemed the “sprinkler fight.”

With only minor changes, the exterior of the Mann house is largely intact. The interiors have not fared so well. There are still 19 apartments in the building that housed one of the early 20th century’s most colorful publishers—a man able to instill terror in the hearts of New York’s wealthiest citizens.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT