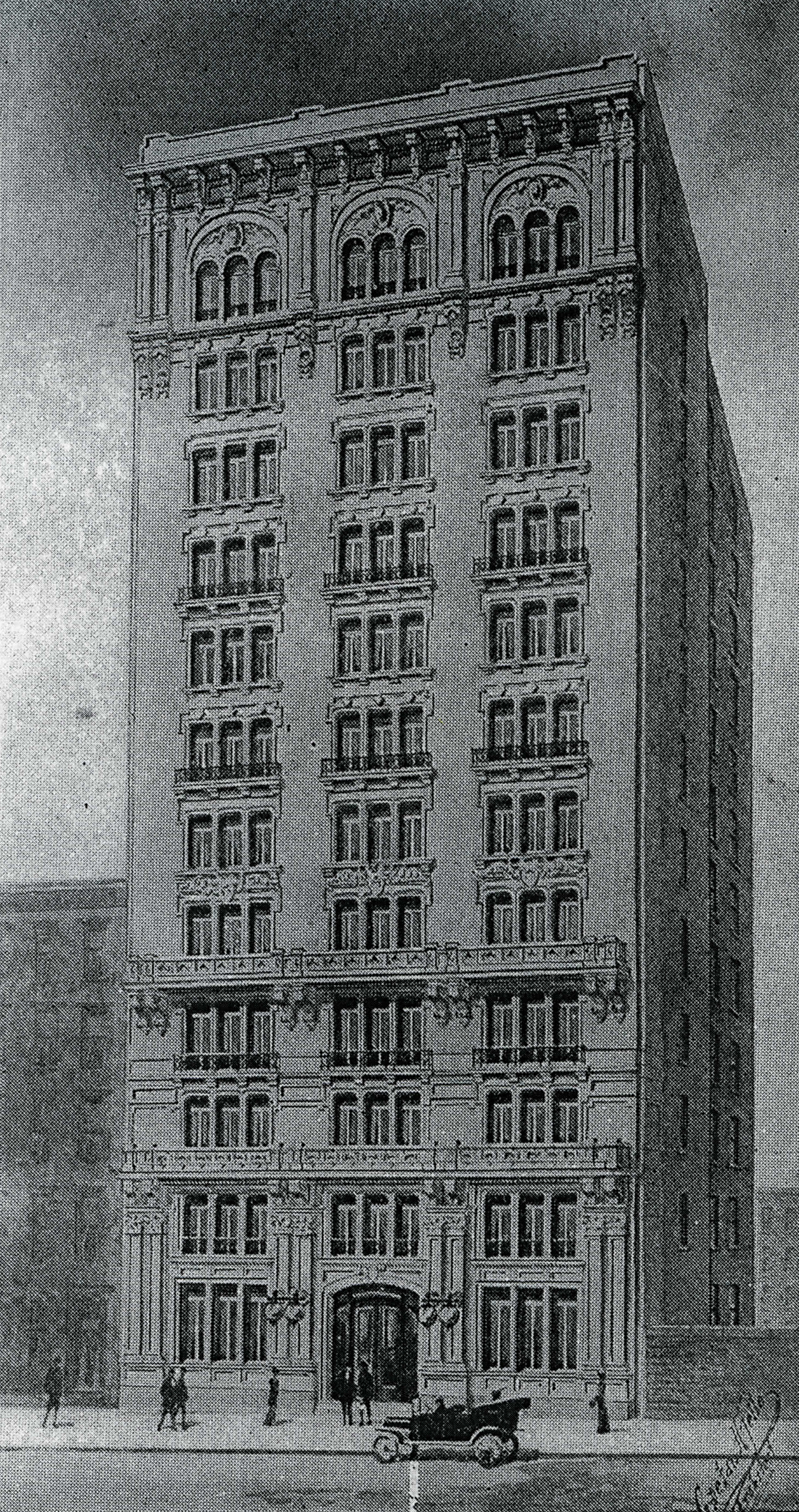

View of 305 West 72nd Street from southwest. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Luxonia

by Tom Miller

One of the earliest signs that change was coming to the mansion-lined West 72nd Street arrived in December 1912, when architect Gaetan Ajello filed plans “for the 12-story apartment house to be erected in the north side of 72d st,” as reported by the Real Estate Record & Guide. Replacing the three residences at 303 through 307 West 72nd Street, the Luxonia would cost its owners, the A. Campagna Construction Co., the equivalent of $8.25 million in today’s money to construct.

Born in Sicily, Ajello was well-known for his apartment building designs. It was he, according to his sister, who gave famed architect Rosario Candela his first job. His design for the Luxonia was a courtly take on Renaissance Revival. Completed the following year, its two-story base was distinguished by full height, paneled pilasters and grouped windows. Full-width stone balconies fronted the third and fifth floors, while three bronze railed balconies adorned the openings of the fourth. Three large heraldic shields clung to the façade between the fifth and sixth floors, the central example adorned with the initials of A. Campagna. The three groupings of windows at the top floor, above a bracketed cornice, sat within ornate Venetian style frames.

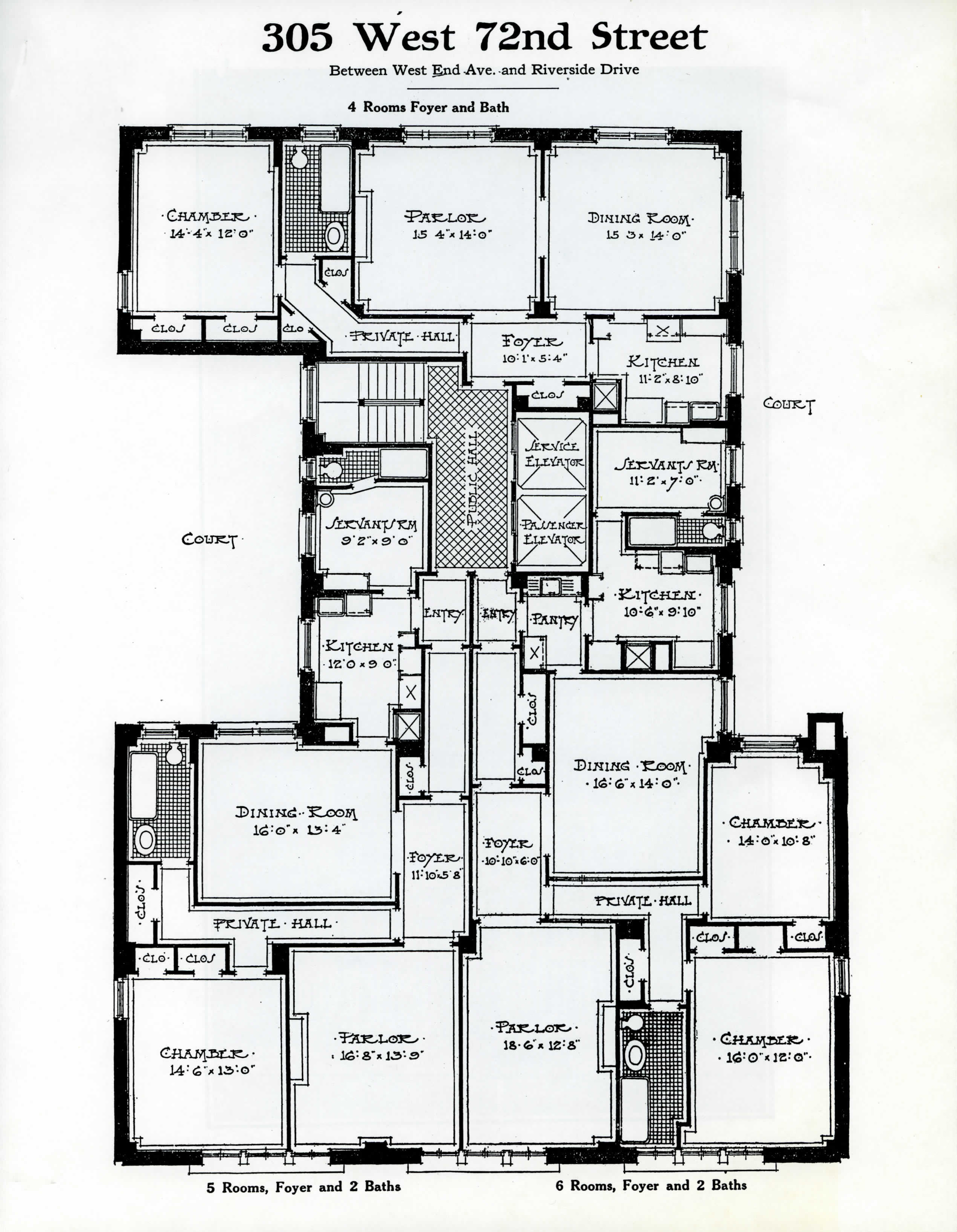

An advertisement in October 1913 touted “Exclusiveness, Elegance, and Character are the predominating features of the apartments in the Luxonia.” The apartments, of four, five or six rooms and one or two baths, boasted “extra large rooms,” and “large and numerous clothes and linen closets.” The least expensive rent was the equivalent of $2,250 per month today.

Among the first residents were artist George H. Barrett, Jr. and his wife. Barrett, known for his landscape paintings, had a studio at 27 West 65th Street. Around the time they moved in, Mrs. Barrett advertised her automobile for sale. A “white-haired man, who called himself George Lambert,” as described by The New York Times, agreed to buy it. “His manner was straightforward,” said the newspaper, and his offer to give a deposit of $100 and pay the $1,250 remainder off in monthly installments was agreeable to Mrs. Barrett.

But when the expected payment did not come, Mrs. Barrett went to the police. She looked through the photographs in the Rogues’ Gallery, until she saw the face of a “white-haired, soldierly looking man.” She identified him as the culprit.

On November 10 The Evening World reported, “George Lambert Lewis, a fine looking man with gray hair and beard, tall, heavily set and looking like a prosperous lawyer or doctor, though the police say he is known to them as Dr. Camp, Eggleston, and Lambert, as well as his latest name, was arrested at Fifth avenue and Twenty-fifth street this afternoon.” The 62-year-old conman declared “It’s an outrage!” although police noted he had served 11 years and six months in Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York. Only two months previously he had been released from Blackwell’s Island.

Before being locked up, Lambert took a swipe at his victim. “If she gave [the automobile] to me outright it wouldn’t pay me for the time I spent listening to her read her poems, to her discussions on religion and reading the Christian Science books she kept forcing on me.”

“If she gave [the automobile] to me outright it wouldn’t pay me for the time I spent listening to her read her poems, to her discussions on religion and reading the Christian Science books she kept forcing on me.”

Ruth Austin was another early resident. Her name appeared in the newspapers for shocking reasons in April 1914. Stockbroker James Murray Mitchell and his family lived in the luxurious Hotel Gotham on Fifth Avenue and 55th Street. He and his wife, Anna, had three daughters. But in 1913 Mitchell left them and moved into the Luxonia with Ruth Austin. At one point, according to The New York Times on April 2, 1914, “his eldest daughter went there to ask her father to come home.” The little girl was just ten years old.

Anna A. Mitchell sued Ruth Austin for alienation of her husband’s affections. Her suit claimed that by “offers of money and otherwise,” she induced Mitchell “to forsake his family and reside with her.” She further charged that Ruth “still harbored and detained,” James Mitchell. It may have been the scandal, or perhaps pressure from the building’s management, that resulted in Ruth’s quickly gave up her apartment.

William Jesse Worden and his wife, the former Estella Alberta Wolcott, lived here at the time. Worden was president of the Worden Efficiency Sales Co. The couple had two sons, Gerald Wolcott, who was 24 years old in 1914, and William Theodore, who was 13.

Gerald lived in Massachusetts where, according to the Newark Evening Star, he was “a wealthy Springfield real estate dealer.” The Worden’s Luxonia apartment was the scene of happy anticipation on August 4, 1915, as preparations were made for Gerald’s wedding to Eunice Louise Hoag that afternoon. It was a special date—William and Estella’s wedding anniversary. Gerald picked up his 21-year-old fiancée in his roadster at 4:00 a.m. and headed to Manhattan. He rounded a turn about eight miles north of New Haven, Connecticut when “a charcoal wagon suddenly appeared in front of the automobile,” as reported by The Sun. “Mr. Worden in an effort to prevent a collision turned suddenly to the right. The car skidded a short distance and then overturned, pinning Miss Hoag underneath.” The couple would not make it to the Worden apartment. Gerald was taken to the New Haven Hospital with broken ribs and other injuries. Eunice died on what was to be her wedding day.

Henry Stemper was a grain broker who, according to The Evening World on June 16, 1916, maintained “an expensive apartment in the Luxonia, No. 305 West Seventy-second Street.” Born in Germany in 1864, he had been a paymaster in the Navy. He married Anna Dachfell in 1894 when he was just starting out in business. But in 1906, the couple separated. Anna later explained, “Henry was a poor young man when we married…But he prospered in the grain business from the start and finally reached the point where he wanted livelier companions. I had an invalid mother to care for and had no desire for the pleasures he liked.” There were no apparent ill feelings between the two. Henry called on Anna occasionally and supported her.

Anna Stemper’s mother died on June 14, 1916. Upon hearing the news, Henry went to her home at around 6:00. After being estranged for ten years, Henry seems to have had a change of heart. Anna said, “in tears [he] told me he was tired of his method of living and was anxious to come back. We agreed to resume life on the old basis.”

Henry had planned an automobile trip to Long Island that evening. In the car with him was his chauffeur, John V. Holmes, three friends from Cincinnati, and Helen Cameron, who lived on Riverside Drive and identified herself as Henry’s niece. As had happened with Gerald Worden, the trip would end tragically.

The touring car was involved in a collision near Springfield, Long Island and Henry was killed. Anna Stemper had not only lost her mother that morning, but now her husband that night. The situation was about to go from very tragic to slightly bizarre.

Helen Cameron went to Jamaica Hospital to claim Henry’s body. As she waited for the necessary papers to be made out, an undertaker from New York appeared and claimed the body on behalf of Anna Stemper. The Evening World reported, “Miss Cameron protested that there was no such person and that she was the only relative authorized to receive the body.” The undertaker produced the wedding certificate Anna had provided to support her claim of the remains. The body was turned over to Anna and on June 16 The Evening World wrote (somewhat dramatically), “In the darkened front room of a modest flat at No. 1332 Lexington Avenue, a plain little woman sat grieving to-day beside the bier of a husband who left her ten years ago.” Towards the end of the article, the writer noted, “Mrs. Stemper said that she was sure the young woman known as Miss Cameron was not a niece of the dead man. She added that Stemper had no relatives in this country.”

Residents of upscale apartment buildings like the Luxonia often traveled to Europe, and in June 1921 Mrs. Jeannette Hannah Thompson made her first trans-Atlantic crossing. She returned on the French liner Paris on September 10. The New York Times said she “attracted the attention of Customs officials by carrying a golden-haired, blue-eyed, life-sized doll in her arms, stylishly dressed.” Were it not for the doll, Jeannette may have passed through the checkpoint without trouble. But an official now noticed that she declared that the expensive gowns in her trunks had “been bought in this country and taken abroad by her.” She declared a little over $100 worth of dutiable property.

The Customs agent asked casually, “Did you take much baggage abroad with you?”

“No, not very much,” she answered.

“How long have you been away?”

“About three months.”

The agent did not have to hear any more. “Well, don’t you think it would be better not to swear off the $800 worth of gowns and admit they were purchased in France?”

Jeanette admitted her ruse—one that went so far as to remove the French labels and sew on American replacements. But, she insisted, “it was her first voyage abroad [and] she was not aware what a serious thing it was to attempt to smuggle goods.”

At the time, the Luxonia was attracting residents from the entertainment industry. Living here was actress Eva Tanguay, known nationwide as “The Queen of Vaudeville.” She was among the highest paid performers of her day, earning as much at $3,500 a week in 1910 (close to $100,000 today). On October 21, 1923 The Morning Telegraph reported that Eva “is about to wind up a successful vaudeville engagement and hie herself to Hollywood for the Winter and furnish a new home. For this reason, she is about to place her artistic home effects and art objects, gathered during many years of travel on the auction block.”

Jeanette admitted her ruse—one that went so far as to remove the French labels and sew on American replacements. But, she insisted, “it was her first voyage abroad [and] she was not aware what a serious thing it was to attempt to smuggle goods.”

Listed among the items being auctioned from her Luxonia apartment were “rare carved teakwood furniture purchased at the San Francisco Panama Fair, Chinese and Persian rugs, tapestries and Sheraton furniture.”

Living here at the same time were actor Hugh Dillman McGaughey and his wife, actress Marjorie Rambeau. Marjorie first appeared on stage in 1901 as a child at San Francisco’s Alcazar Theatre. She appeared in several silent films and would have her first talking role in Her Man in 1930. She would go on to be twice nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. The couple was divorced in 1923 and Hugh married Anna Thompson Dodge in 1926. The heiress of the Dodge Automobile fortune was 19 years older than her husband.

Other residents connected to the entertainment industry were theater producer John W. Allcoate, here in 1925; and producer and impresario Milton Aborn, and his wife Marjorie. Aborn was perhaps best known for his revivals of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.

The widely talented Guiseppe Maria Bombaschek was born in Trieste, Italy, in 1890. At the age of 13 he was a professional organist, and at 18 was conducting concerts. He came to New York as a young man, and in 1913 became a conductor for the Metropolitan Opera, a position he held until 1929. He was, as well, a pianist, film director, and voice coach. Among his students were Beverly Sills, Jeanette MacDonald, and Franco Alfano.

On February 3, 1938, Bomboschek was to appear in a concert in Hanover, Massachusetts, but just before the curtain rose, he was stricken with an attack of appendicitis. The New York Sun reported that he “was rushed to Boston. There he was placed on a train for New York.” The conductor was operated on at the Jewish Hospital in Brooklyn. Despite what seems to be a convoluted process, the surgery was a success.

Among the Luxonia’s most colorful residents was Lew Burston, here in the 1940’s. Born in New York around 1896, he had originally been a theatrical agent. But in the post-World War I years he turned to boxing management. He was Madison Square Garden’s scout for European boxers and managed some of the most famous boxers of the era.

While Gaetan Ajello’s handsome apartment building has lost its name and now goes only by its street address, it has retained its patrician appearance. Sadly, the stone balustrades of the third and fifth floor balconies had been removed, but otherwise the building is happily intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT