A fit of the blues and recurring dizziness…

by Tom Miller

In 1919, two decades after the fact, The Northeastern Reporter explained the rise of a string of lavish mansions at the foot of Riverside Drive, all designed separately by a single architect.

“In 1896 one John S. Sutphen was the owner of the entire block between Seventy-Second and Seventy-Third streets fronting on Riverside Drive. He formed a general plan to improve and develop the land, and filed in the office of the register a map dividing it into lots.” The first sale, according to the Reporter was in June, 1896, including a plot “to one Kleeberg.”

Philip Kleeberg’s deed included restrictions similar to the others. Kleeberg, “his heirs and assigns, shall, within two years from the date hereof, cause to be erected and fully completed upon said lot, a first-class building, adapted for and which shall be used only as a private residence for one family, and which shall conform to the plans being made by C. P. H. Gilbert, architect.”

At the time developers intended that Riverside Drive would rival or surpass Fifth Avenue with palatial dwellings. Its superb views from above the Hudson River and the manicured Riverside Park were its answer to Fifth Avenue’s Central Park. Sutphen may have been friendly with the mansion architect Gilbert; or perhaps he chose him to do the work simply because he knew and trusted his well-earned reputation.

Philip Kleeberg and his wife, Maria, wasted little time in setting the gears in motion. Within four months, on October 3, 1896, The American Architect and Building News announced Kleeberg’s plans to build a “four-story brick dwelling to cost $55,000, on Riverside Drive, near 73d St.” Including the price of the land, $145,000 according to The New York Times, the outlay would be more in the neighborhood of $5 million today.

The Kleebergs were relatively young and the aggressive businessman’s fortune came from a variety of enterprises. Originally involved in the wholesale lace business, he was by now also President of the Frog Mountain Ore Company, Vice-President of the Colonial Oil Company, and held directorships in the New York Petroleum Company, the William Radam Microbe Killer Company, the Alabama and Georgia Iron Company, and the Empire Steel and Iron Company. Years later, he would invent a calculator and in 1916 become President of the National Calculator Company.

Construction of 3 Riverside Drive took two years and as it neared completion, The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide gave a hint at the high-end details when it reported that the Hernsheim Architectural Iron Works was at work on a “bronze vestibule gate for the handsome dwelling No. 3 Riverside Drive, Chas. P. H. Gilbert, architect.” Construction was completed in 1898 and the Kleebergs, who had lived at 56 East 73rd Street, now defected in a nearly straight line across the park.

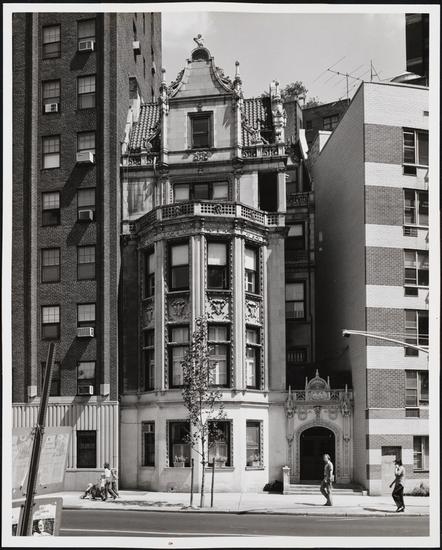

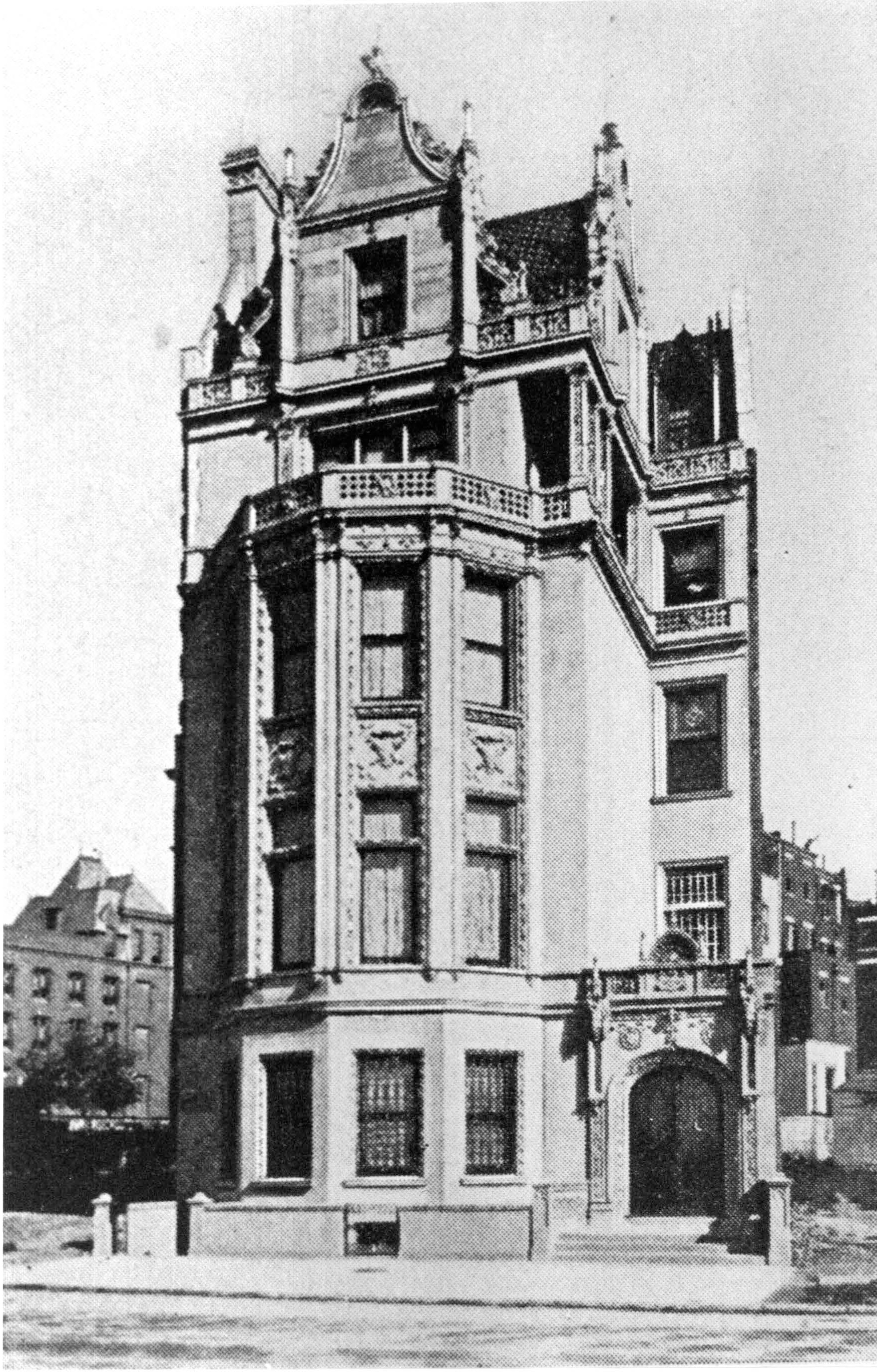

Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert had produced a sumptuous confection in a frothy style so nebulous as to put architectural historians at odds. The AIA Guide to New York City calls it “freely interpreted Dutch Renaissance;” while the Landmarks Preservation Commission argues it is “French Renaissance Revival.” Late 19th century American architects were not wont to concern themselves with historical purity; and elements of both styles can be detected in Gilbert’s design.

Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert had produced a sumptuous confection in a frothy style so nebulous as to put architectural historians at odds. The AIA Guide to New York City calls it “freely interpreted Dutch Renaissance;” while the Landmarks Preservation Commission argues it is “French Renaissance Revival.”

The architect set the entrance to the side, allowing for a spacious parlor looking onto the park. The mansion’s bow-fronted façade stopped at three floors, allowing Gilbert to provide a “terrace” at the fourth floor accessed by a long square-columned gallery to the side. The elaborate stone gables, ornamented with spiky finials and florid s-shaped brackets, culminated in deeply-carved shells. In a somewhat tongue-in-cheek gesture, Gilbert perched a stone cherub holding a bowl of fruit at the pinnacle.

Whereas the mansion was solid, the Kleebergs’s marriage may have been a bit shaky. The title to the new mansion was put in Maria’s name, as was expected. And the family, including three sons, moved in and outside appearances were maintained. However, Philip reportedly acquired a second home on the Upper West Side for his own use.

Gradually the row of houses around 3 was constructed. By September 7, 1901 the Record & Guide reported “three lots of the plot have been sold, one to Philip Kleeberg, one to Colonel W.L. Trenholm, and one to Mrs. Prentiss, all of which have been improved.”

For years, nothing other than the expected entertainments and social functions at 3 Riverside Drive was the norm. Then, six years later after moving in, a heart wrenching tragedy would occur. The Kleebergs participated in the routines of wealthy New Yorkers. Philip and Maria spent the first two months of the summer of 1903 in Europe and upon their return she left for “the country.” Society women at the time would summer in resorts or estates like Newport and Bar Harbor, while their working husbands would join them on the weekends.

On August 18, the 48-year old socialite returned to New York, a bit early in the season. Six days later she hosted a dinner party “and a number of Mr. and Mrs. Kleeberg’s relatives and friends were present,” said The Sun on August 24. Following dinner the party took a drive along Riverside Park, then returned to the terrace of the mansion where they sat and chatted.

At one point Maria Kleeberg excused herself, saying she was going to the bathroom. When she did not return, her sister became concerned and followed. The Sun reported “She opened the door just as Mrs. Kleeberg put a bottle to her lips. Mrs. Sands knocked the bottle, which was filled with carbolic acid, to the floor.”

In doing so, Maria’s sister was badly burned on the hands. She rushed downstairs and instructed the servants to find a doctor. Three doctors were sent for, but none of them was at home.

Notoriety was one thing the wealthy desperately attempted to avoid; so it was only through desperation that an ambulance was called for from Roosevelt Hospital. It caused precisely the attention the family was attempting to avoid.

“The arrival of the ambulance caused great excitement in the neighborhood. One of the rumors which were circulated had it that someone had been murdered in the Kleeberg house. At one time there were at least 300 persons in front of the house,” said The Sun.

By the time the ambulance had arrived, Maria Kleeberg was dead. The police, attracted by the ambulance call and the crowd, attempted to investigate. In an attempt to avoid even worse publicity and scandal, the doors were barred against the police. No information was given out until Detective Culhane refused to allow the body to be removed until he was let in.

Forced to face reporters, Philip Kleeberg insisted there was no reason why his wife should have committed suicide. His only explanation was that she may have had “a fit of the blues.”

Kleeberg soon transferred the title to his son, 21-year old Gordon S. P. Kleeberg. The young homeowner was possibly a difficult man to work for. On February 23, 1906, he placed an ad in the New-York Tribune seeking a coachman. “Good, careful driver; competent; painstaking.” He asked for the “best written and personal references.” Later that year another advertisement was placed, for the same position. Then on September 21, 1906, yet another advertisement appeared. “Coachman—Thorough horseman; care of horses, carriages, and harness; strictly sober, honest, willing and obliging.” It would seem that young Kleeberg had unusually bad luck in finding a coachman; or he was simply too difficult to work for.

In the meantime, the home life of William Guggenheim, known as “The Smelting King,” had become rocky. Born into the fabulously wealthy mining family, his domestic differences with his wife, Aimee, became such that the couple separated. In 1908, he purchased 3 Riverside Drive. But he barely had time to unpack his bags.

On May 3, 1910, the New-York Tribune reported that Guggenheim had sold the house to “a Mr. Hopkins, who will occupy it.” The development of the block was reflected in the asking price–$200,000, or about $4.75 million today. The Tribune said that a negotiated price of $165,000 was said to be the actual sale price. In commenting on the sale, the newspaper said “The house is one of the finest in the lower part of the drive.”

It was not uncommon in the first decades of the 20th century for wealthy purchasers of real estate to play a cat-and-mouse game with the press regarding their identities. A little over a month later, on June 14, the New-York Tribune said “The new owner is said to be a woman, who by the purchase obtains control of half the block.”

Finally, on July 16, 1910, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide ended the speculation, naming Mrs. Angie M. Booth as the buyer. “Mrs. Booth is the owner of the adjoining property on the north, including the southeast corner of 73d st.”

Angie Booth was the wife of Henry P. Booth, and in a surprising turn of events, she resold the property prior to 1915—to William Guggenheim. Angie Booth would live to regret it. Rather than move back into the mansion, Guggenheim initially ran it as a boarding house; then rented it to Dr. William H. Wellington Knipe at $4,000 a year for the first year, and $5,000 a year for the next four years. It was a hefty rental price; but Knipe had income-producing plans for the property.

Dr. Knipe was “one of the first physicians in New York to become interested in twilight sleep,” said The Sun on January 22, 1916. “Twilight sleep” was a procedure used on women going into labor that was intended to reduce the pain of childbirth. The Guggenheim mansion became Dr. Knipe’s “twilight sleep sanitarium.”

Angie Booth, who lived next door to the house, and Mary T. Sutphen whose own mansion was at the corner of Riverside Drive and 72nd Street, were outraged. They filed suit to close down the sanitarium.

Recalling the restrictions in the original Kleeberg deed, their lawyer explained “The plaintiffs contend that the block is restricted to residential purposes and barred from trade and business.” His female clients were a bit more pointed, calling the sanitarium “a menace to the peace and quiet of the neighboring landowners,” and “obnoxious and offensive.”

The Sun said that Knipe felt his neighbors were “needlessly alarmed” and “said he had talked with many of his neighbors and they told him they preferred the proposed sanitarium to the ‘exclusive’ boarding house formerly conducted here.” One of these was Lydia Prentiss.

Dr. Knipe was “one of the first physicians in New York to become interested in twilight sleep,” said The Sun on January 22, 1916. “Twilight sleep” was a procedure used on women going into labor that was intended to reduce the pain of childbirth. The Guggenheim mansion became Dr. Knipe’s “twilight sleep sanitarium.”

The wealthy woman, who lived at 1 Riverside Drive, was placed in an uncomfortable position when her neighbors knocked on her door, asking her to join them as a plaintiff. The stalwart socialite held her ground, however, telling the press she “didn’t think women should lend themselves to opposing the development of any treatment that would alleviate or diminish the pains of childbirth.” It most likely put an end to Lydia Prentiss’s invitations to tea at either the Sutphen or Booth residences.

Although the courts ruled in Dr. Knipe’s favor; things returned to normal on lower Riverside Drive. Eventually William Guggenheim moved back in and used the mansion as his private dwelling, restoring peace among the neighbors. Highly educated and erudite, he was the author of several publications, many of them patriotic. Among them were Our Republic Triumphant; Peace by Victory at Last, but with a Warning; A Greater America; and What Price Government. His ardent patriotism was evidenced in 1940 when Italy declared war against Great Britain and France. In 1920 he had been decorated with the Commendatore dell’ Ordine della Corona d’Italia by the Italian Government. Now he renounced and returned the title, saying that the declaration of war came as “a profound shock.”

He remained in the Riverside Drive mansion until his death at the age of 72 on June 27, 1941. The house became the property of the Seamen’s Bank for Savings, which leased it to General Boleslaw Wieniawa-Dlugoszeowski and his wife and daughter. The Polish Ambassador to Italy at the outbreak of war in 1939, he had also been the aide to Marshal Pilsudski, dictator of Poland.

The 60-year old diplomat was subject to what the Polish Consul General referred to as “dizzy spells.” On the evening of July 1, 1942, the general received word that he had been appointed as Envoy to Cuba. Shortly afterward, wearing his pajamas and bedroom slippers, he went to the roof “to get a little fresh air,” according to Sylvyn Strakacz, the Police Consul General. Moments later, he fell to his death.

Despite the Consul’s assertions that the fall was the result of recurrent dizziness; The New York Times said “Police of the West Sixty-eighth Street Station, who helped remove the general to the hospital were uncertain whether the death was an accident or suicide.”

Like William Guggenheim, Gordon Kleeberg could not stay away from 3 Riverside Drive. On New Year’s Day, 1944 The New York Times reported “One of the finest town houses on the West Side figured in the news yesterday when Lieut. Col. Gordon S. P. Kleeberg purchased the building at 3 Riverside Drive which was erected by his father in 1896.”

Although the newspaper got the architect’s name wrong, citing Cass Gilbert rather than C. P. H. Gilbert; it correctly described the interiors. “Among its features still in a good state of preservation are a marble stairway, solid cherrywood floors and bronze grill entrance doors.” The article said “Colonel Kleeberg intends to remodel the building into small apartments after the war and occupy the terrace suite.”

As promised, in 1951 the 37-foot wide mansion was divided into two apartments per floor. Happily, much of C. P. H. Gilbert’s interior detailing was preserved. In 1995 it was purchased by real estate developer Regina Kislin for $10 million. She and her husband, photographer Anatoly Siyagine, embarked on a long restoration project to bring the house back to a private home.

Included in the renovation were modern touches that Maria Kleeberg would have found shocking—an indoor pool, sauna and gym, for instance. Seventeen years later, she put the 18-room house on the market for $40 million. Real estate listings noted “six bedrooms, eight and a half bathrooms, a two-room staff suite, four terraces, and an elevator.” When no buyers appeared, Kislin reduced the price to $30 million in September 2014.

The magnificent Gilbert-designed mansion survives as a stunning reminder of the first days of the development of Riverside Drive when developers lured millionaires from the east side of Central Park.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT