The Incident of the Revolving Door

by Tom Miller

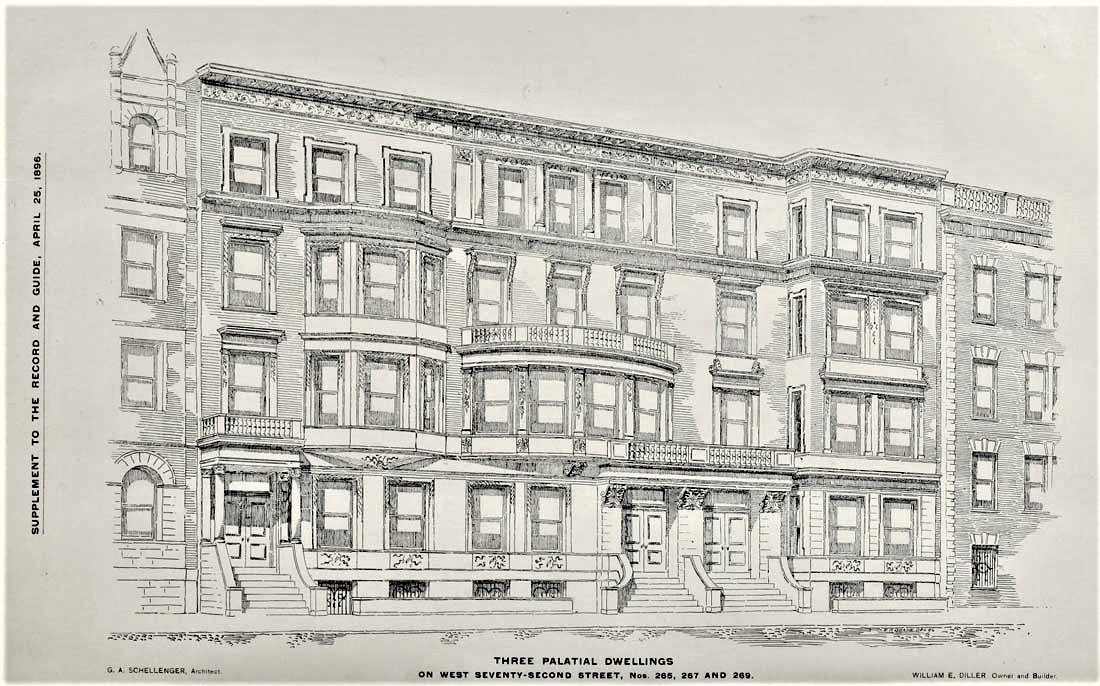

On April 25, 1896 the Record & Guide reported on the newly completed houses at 265 through 269 West 72nd Street, just east of West End Avenue. Erected by developer and physician William E. Diller, the journal said, “In this operation Dr. Diller has evidently has in mind the wants of people of quite large means.” Designed by architect Gilbert A. Shellenger in the Renaissance Revival style, each was an ample 25-feet wide and rose four stories above an English basement. Faced in brown Roman brick, they were liberally trimmed in brownstone and had cost Diller $35,000 each to construct–just over $1 million apiece today.

The critic of the Record & Guide was taken by the upscale homes, saying they the interior spaces “are as stately in their proportions as they are excellent in fittings and finish.” Costly trims were executed in “mahogany, curly birch, sycamore, birdseye maple and quartered oak–finished in the highest style of the polisher’s art.” The parlors, dining rooms and “dressing salons” boasted parquet floors and the exposed plumbing was silver plated. Each of the homes had three bathrooms–two for the family and one for the servants. The family baths included “a Turkish needle and shower bath, and everything requisite to luxurious bathing.”

Perhaps surprisingly, 265 West 72nd Street, the easternmost of the trio, was being operated as a high-end boarding house by the first years of the 20th century. The well-heeled residents in 1905 included W. R. Bascomb, a civil engineer employed by the city’s Department of Bridges. Society pages too notice of a house guest the following year, the New York Herald mentioning on April 16, 1906 “Miss Hastings, of Dallas, Texas, is at No. 265 West Seventy-second street.”

Another boarder was Maxwell Smith a zoologist who specialized in the study of the shells of mollusks. In 1907 he published an article in the Bulletin of the Brooklyn Conchological Club entitled “A New Varietal Form of Turbo Petholatus, Linn.”

Another boarder was Maxwell Smith a zoologist who specialized in the study of the shells of mollusks. In 1907 he published an article in the Bulletin of the Brooklyn Conchological Club entitled “A New Varietal Form of Turbo Petholatus, Linn.” And at the International Zoological Congress held in Boston in August 1908, he was among a group interested in forming an American Conchological Society.

Living here by 1907 were Effie Brown and her daughters Isabel and Marjorie. The former Effie Alida Brower, her husband Alexander Ferguson Brown had died in 1884. Effie’s impressive pedigree earned her membership into the Colonial Dames of America.

Marjorie Ferguson Brown was married on January 15, 1908. The social importance of the groom’s family outshone that of the bride’s and the society columns somewhat brutally pushed Marjorie to background in reporting the event. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote “Robert Harley Sherwood, jr.’s wedding at the St. Nicholas Collegiate Church, Manhattan, yesterday–Mr. Sherwood’s bride being Miss Marjorie Ferguson Brown of 265 West Seventy-second street–was not at all a big function. Several hundred people only, relatives and close friends alone, were present at the church and at the reception later at the Hotel Buckingham there were relatives alone.” Effie Brown moved to New Jersey not very long afterward.

In 1909 Moses Greenwood, Jr. and his wife, the former Margaret Woods, moved to New York City from St. Louis, Missouri where he had made a comfortable fortune in real estate. On the night of April 3, 1911, the Greenwoods and their niece attended the theater and then went to the fashionable Louis Martin’s restaurant on Broadway. On entering, the young man operating the revolving door (according to Greenwood later), “moved it so that the two women were squeezed into one compartment.” Martin scolded the young man who “replied insolently.”

After being shown to their table, Greenwood sent for Mr. Martin and reported what had happened. Thirty minutes later Martin came back to inform Greenwood that Henry P. Hopkins had been fired. It was apparently too much for Hopkins to handle. He had only taken the demeaning job because he was unable to find work as a druggist clerk, the position for which he had been schooled. And so, he lurked in the shadows outside awaiting Greenwood’s appearance.

The Greenwoods left Martin’s at about midnight. They walked to the subway station at 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue and just as Greenwood started down the steps he was hit from behind. The New York Herald reported “At the moment he was struck with a brick an automobile tire exploded, and thousands thought the man had been shot.” Greenwood lay, stunned and motionless, at the bottom of the steps.

Henry P. Hopkins fled, but the assault had been witnessed by several policemen. They chased him, “followed by several hundred men,” said the article, who finally overtook him two blocks away. If Moses Greenwood had been irritated by Hopkins’s handling of the revolving door and insolence, he was furious now. He filed charges of felonious assault.

By the World War I years West 72nd Street was changing from a fashionable address to a shopping thoroughfare. The owner of 265 West 72nd Street, Mrs. Marion K. Clark, hired architect C. B. Brun to design renovations in December 1917. The cost of the project would be just under a third of a million in today’s dollars.

The article noted “Neighborhood mothers are encouraged to bring the children when they shop or browse” and noted “slightly older children may be parked in a ‘kiddie-den’ at the entrance. Shaped like a small circus tent, the den is equipped with coloring books and crayons to entertain the young.”

Completed in 1919, the renovation resulted in the stoop being removed and a flat-faced, two-story storefront installed. The interiors which the Record & Guide had so highly praised in 1896 were now broken up into apartments. An advertisement in The Sun on July 18, 1920 offered “2 Rooms and Kitchenette” for between $1,600 to $1,900 per year. The agent was Earle & Calhoun, whose offices were in the building. The firm would remain at least until 1946.

Another early commercial tenant was the Ansonia Radio Corp., here by 1927. It was an authorized retail dealer of Zenith “Long Distance Radios.”

On November 23, 1964 The New York Times wrote “Adding to the renaissance of the West Side–along with Lincoln Square and urban-renewal projects, is a new branch of Creations ‘n’ Things.” The broad array of merchandise ranged from gourmet foods to greeting cards, kitchen gadgets and apparel. The article noted “Neighborhood mothers are encouraged to bring the children when they shop or browse” and noted “slightly older children may be parked in a ‘kiddie-den’ at the entrance. Shaped like a small circus tent, the den is equipped with coloring books and crayons to entertain the young.” Creations ‘n’ Things remained for about two decades in the space.

The fraternal siblings of the brick-and-brownstone residence were demolished decades ago, leaving 265 West 72nd Street appearing rather vised in between two more modern structures. By peering above the 1919 storefronts the passerby can see the beautifully intact upper floors of the house that was once deemed “palatial.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

265 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 265 West 72nd Street:

Meet Imbert Jimenez!