The Non-Hudson Towers

by Tom Miller

In 1923 Physi-Surge-Rhue, Inc. announced groundbreaking news—the planned construction of a 22-story combination hotel and hospital to be known as Hudson Towers at the northwest corner of 72nd Street and West End Avenue. In its July issue that year American Medicine reported “The building is to provide a combination of a modern hotel with features for the needs of physicians and their patients. In addition to a large dining room there will be 358 chambers, 81 special rooms, 211 baths and 12 public baths.”

It was an unheard-of concept aimed at filling a need both for patients and their families. The Dental Outlook asked, “Where can the young woman, who is not a charity patient, go when her baby is born? There are some hospitals which have private rooms available for this purpose, but all too few for the demand.” The journal interviewed Dr. Leo Buerger who explained, “In Hudson Towers the mother will be able to stay under the same roof with her sick child, and the father can occupy a suite with his wife and newborn child. There are to be suites for the accommodation of relatives and for patients who feel they can afford them for themselves…There will be no heart-breaking hospital rules to banish the worried relative, to leave the sick child crying for its mother or sent the troubled wife to her desolate home while her husband lies suffering miles away.”

Excavation for the foundation was completed in December 1923, at which point the Record & Guide noted its depth had “reached greater than that of the Woolworth Building.” Four months later, on April 27, 1924, the cornerstone of the $3.5 million structure was laid. In it were placed “a complete record of modern medicine,’ according to The Modern Hospital, “in the form of a reel of motion picture film showing doctors performing important operations, together with glass stained specimens of all known disease-producing bacteria, and a collection of drugs regarded as specific cures for diseases, and a record of those diseases now regarded as incurable.”

And then the investors ran out of money. With the shell of the building completed, construction ground to a halt. The idealistic dream would never be fulfilled.

Hudson Towers received a reprieve, somewhat ironically, from the American Contractors War Advisory Committee, which sent a letter to Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia calling demolition “a mistake.” It proposed instead, according to The New York Sun, to finish the building “as a first-class military hospital having a capacity of 1,000 patients in four or five months at a cost of $900,000 or less.”

In 1928, the New York Skin and Cancer Hospital mounted a fund-raising effort to purchase the unfinished building. But that plan, too, was scrapped when only $100,000 of the required $5 million necessary was raised. Hopes for the site were raised in 1932 when Sumner Gerard purchased it at auction for $200,000. But it continued to sit abandoned like a bombed-out shell for years.

On December 10, 1938, The New York Sun reported, “Hudson Towers, twenty-three [sic] stories high, has stood for fourteen years in decaying magnificence on the corner of West End avenue and Seventy-second street. Only the shell of the building ever reached completion. This shell remains, representative of the stuff that dreams are made of; for the skyscraper was planned as the greatest hospital-apartment hotel in the world.”

Now, said the article, “Hudson Towers is about to be completed, turned into a smart apartment house…Work of making the building accommodate two, three, four and five-room apartment units, with twenty-larger terrace apartments and a four-room studio duplex penthouse, will start immediately. Sylvan Bien is the architect.”

But once again, dreams and plans were not to be fulfilled. Four years later, with the United States drawn into World War II, a national scrap metal drive was initiated by the Government. On September 15, 1942, the Utica Observer-Dispatch reported, “No. 1 white elephant and symbol of the all-out character of the drive is Hudson Towers, a 22-story, boarded-up, forlorn building whose empty shell has been haunted for 18 years by the ghosts of high hope and boom-time ambition.” The article noted, “It is expected that the building would yield some 1,500 tons of steel scrap from its girders, besides other metals.”

Hudson Towers received a reprieve, somewhat ironically, from the American Contractors War Advisory Committee, which sent a letter to Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia calling demolition “a mistake.” It proposed instead, according to The New York Sun, to finish the building “as a first-class military hospital having a capacity of 1,000 patients in four or five months at a cost of $900,000 or less.” Because the shell was already completed, it would constitute a significant savings in time and money over building a hospital from scratch.

But that did not happen either.

And then, in June 1945—22 years after ground was broken—the Brooklyn-based building firm of Kenin & Posner purchased the uncompleted structure. The Hudson Towers Corporation was formed, and architect Arthur Weiser was hired to design an upscale apartment building from the carcass of Hudson Towers. His plans, filed on August 1, projected construction costs at around $635,000 in today’s money. But that scheme never came to pass, either.

Finally, on May 27, 1946 The New York Sun reported that a syndicate headed by Joseph Nemervos called the Riverside Towers Corporation, had purchased the outstanding stock of the Hudson Towers Corporation. Once again plans were announced to transform the “hollow shell,” as described by the newspaper, into apartments. The new owners went ahead with Arthur Weiser’s plans and a year later what was now called the Riverside Towers, a cooperative apartment building, was completed. There were two to seven apartments per floor.

Among the well-to-do occupants was Natalie Baird, described by the Long Island Star-Journal as “a wealthy widow of a steel corporation executive.” She maintained a summer home in Bayport, Long Island. In January 1957 she put her apartment on the market through a newspaper advertisement. Two men, James Mitchell and Lawrence Baker, telephoned her, saying they were publishers who needed a place to work “and her apartment seemed to fill the bill.”

The men came by to see the apartment on February 2. Natalie Baird later told investigators, “drinks were served.” The Star-Journal recounted, “Subtly, she said, the conversation was steered into a discussion of art. Mrs. Baird, who speaks French discovered that her visitors could converse fluently in that language.”

And then she passed out. “She believes one of the con artists put a mickey in her drink when she wasn’t looking,” said the article. When Baird regained consciousness the men were gone, as were $30,000 in jewels and travelers checks from her wall safe.

American Ballet Theater prima ballerina Lupe Serrano and her husband, Kenneth Schermerhorn, lived here in the 1960’s. Schermerhorn was the musical director of the American Ballet Theater and of the New Jersey Symphony.

Living in the Riverside Towers at the same time was economist, author, and educator Dr. Louise Sommer. Born in Vienna, she had received her Ph.D. from the University of Basel in Switzerland in 1915. Fluent in German, French, Italian and English, she translated foreign works into English. While living here in 1960 she translated and edited Essays in European Economics Thought. She died at the age of 80 in 1964.

“She believes one of the con artists put a mickey in her drink when she wasn’t looking,” said the article. When Baird regained consciousness the men were gone, as were $30,000 in jewels and travelers checks from her wall safe.

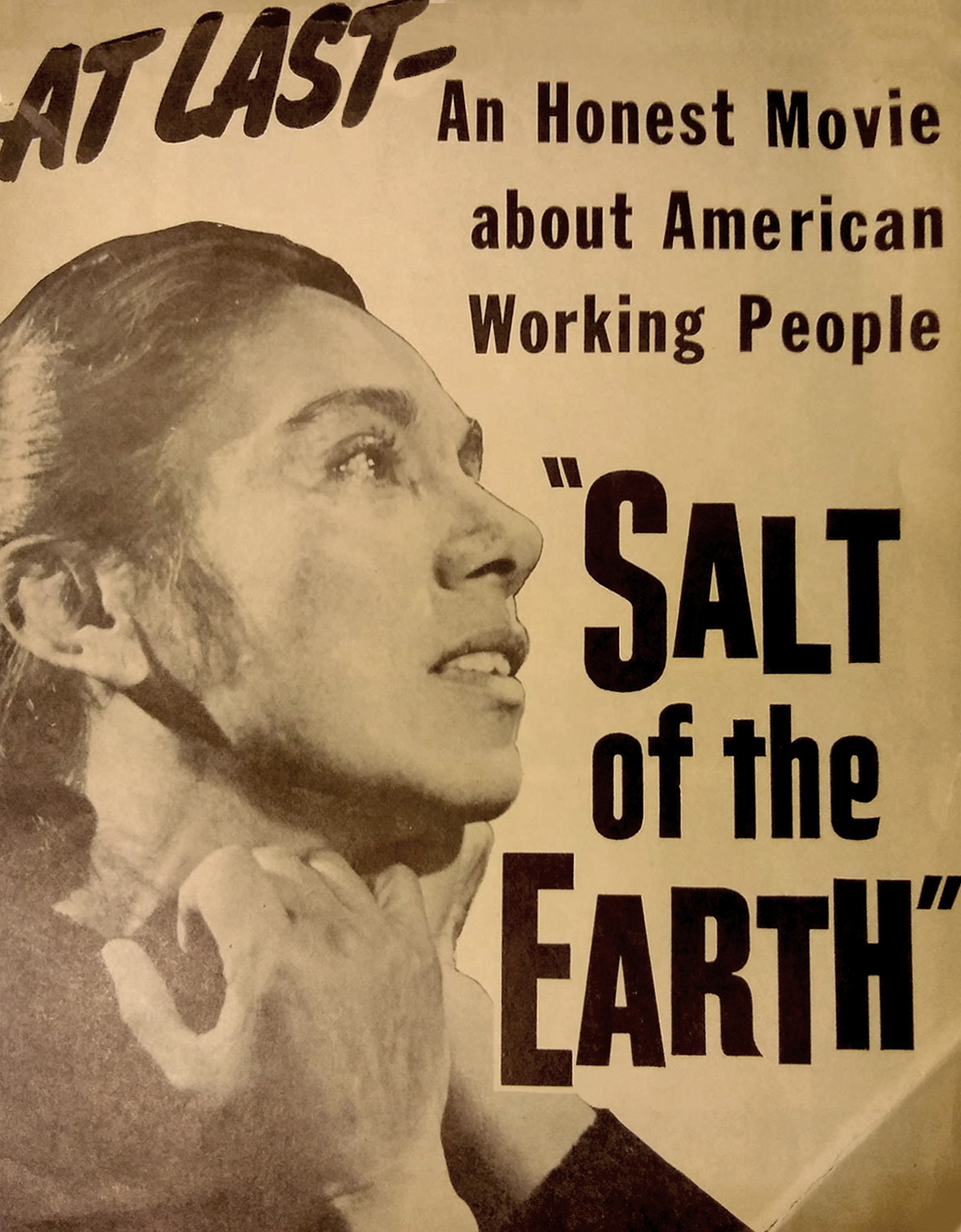

Another resident, Herbert J. Biberman, was the leading director for the Theater Guild and the director of the 1954 award-winning film Salt of the Earth. He had been among the motion picture producers, directors and screenwriters called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in October 1947—the group who became known as the Hollywood Ten.

During that session he refused to answer the question “Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist party?” He based his refusal on the First Amendment, contending that his political affiliations were protected by the guarantees of free speech and assembly. He was convicted of contempt of Congress and in 1950 served a six-month prison sentence in a Federal penitentiary in Texas.

Blacklisted in Hollywood, Biberman’s Salt of the Earth was rejected by theater owners. The New York Times later noted, “In Europe, however, it was voted the best picture of the year by the Motion Picture Academy of France and carried off a top prize of the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in Czechoslovakia.

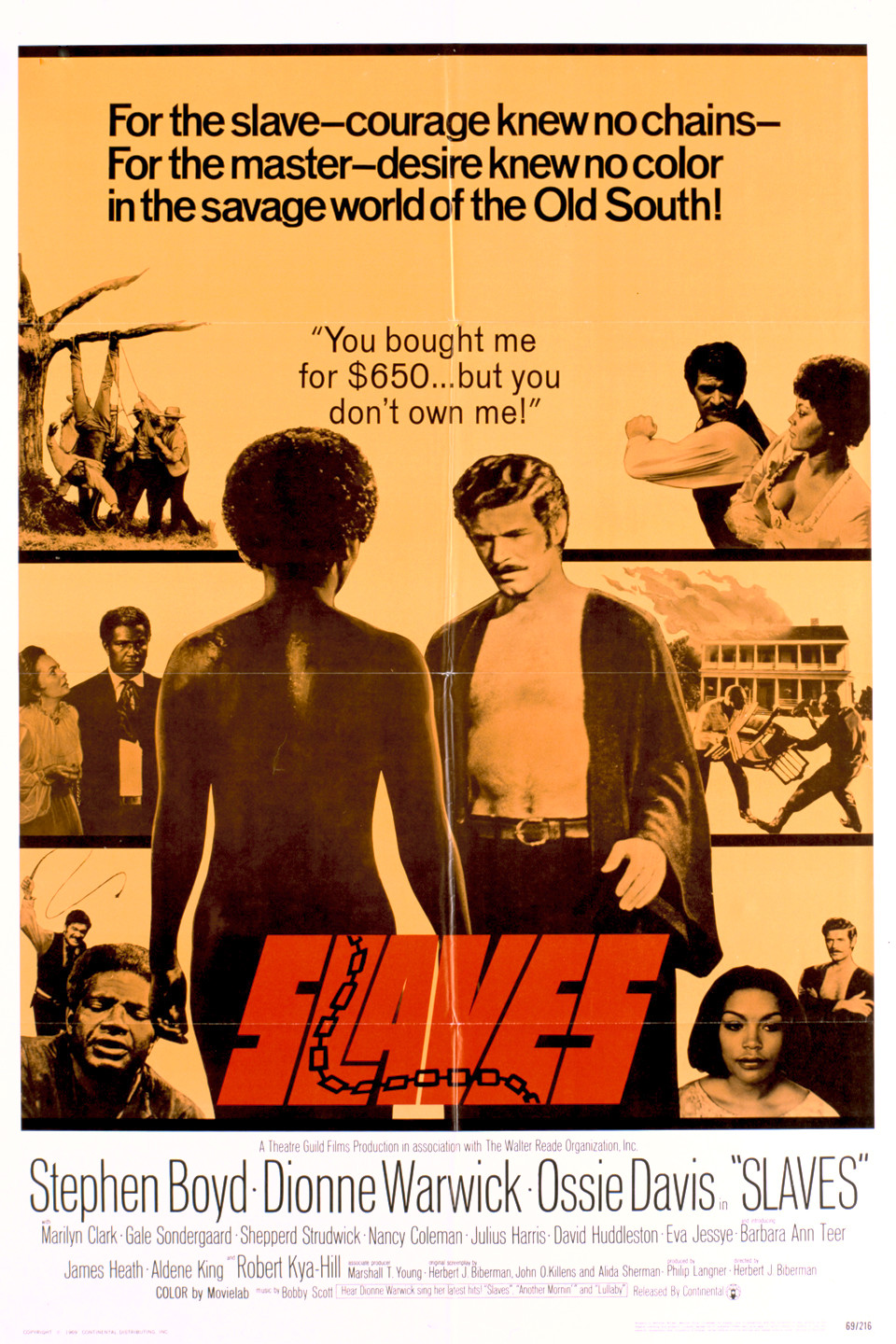

In 1969 Biberman wrote and directed the film Slaves, starring Dionne Warwick (in her screen acting debut), Ossie Davis, and Stephen Boyd. It would be his last work. He was still living in the Riverside Towers when he died on June 30, 1971 at the age of 71.

The Riverside Towers gives no hint today that it was born of an abandoned shell of a hospital-hotel that was never to be or that its backstory is one of the most bizarre in New York architectural history.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

263 West End Avenue

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 263 West End Avenue:

Meet Ann Lang and Ashley Satenstein!