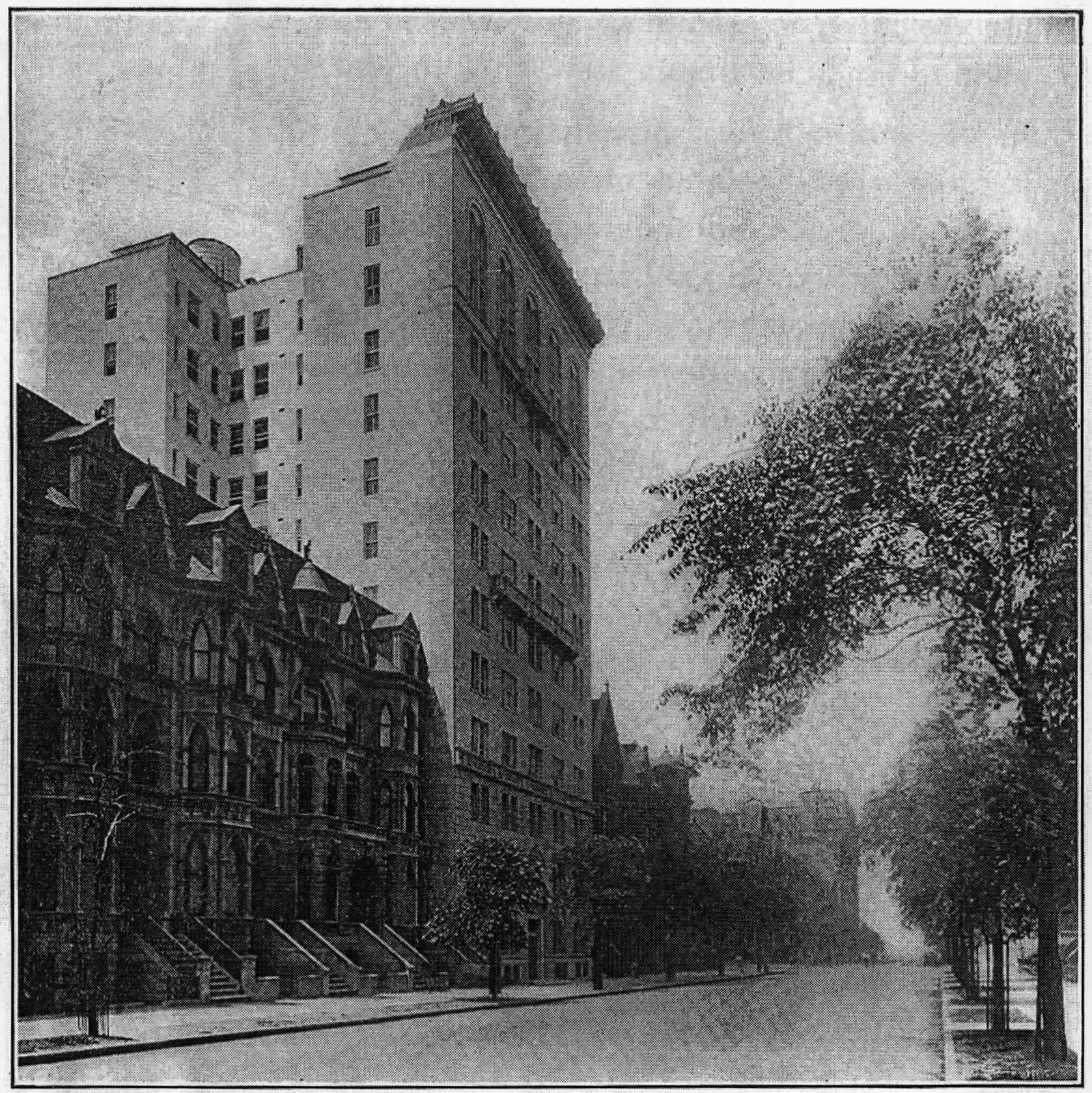

View of 260 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Three’s Company: The Wellwyn Apartments

by Tom Miller

In 1903 two apartment buildings anchored West 72nd Street—the Dakota on the eastern end at Central Park West, and the Chatsworth on the western end at Riverside Drive. In between were private houses, the residents of some of the Upper West Side’s most affluent citizens.

Then, on March 10, 1912, The New York Times reported, “The changing character of West Seventy-second Street from a private residential thoroughfare to a business and apartment house street was still further intensified yesterday in the sale for an apartment house improvement, of the three fine residences at 256, 258, and 260 West Seventy-second Street.” The article explained that the newly formed Wellwyn Realty Company, headed by William B. Symmes, Jr., was behind the project. The journalist went on to say, “the block occupied by the houses just sold is entirely restricted to private dwellings.”

The plans, filed by the architectural firm of Rouse & Goldstone in June, placed the cost of construction of the 12-story building at $250,000—a significant $6.8 million today. Its dignified Italian Renaissance-inspired design was meant to slip quietly among the upscale homes around it. The three-story limestone base, paired arched windows, and Juliette style balconies added to the palazzo character of the building.

An advertisement in 1913 boasted that The Wellwyn sat on a “park thoroughfare” on a “select private house block.”

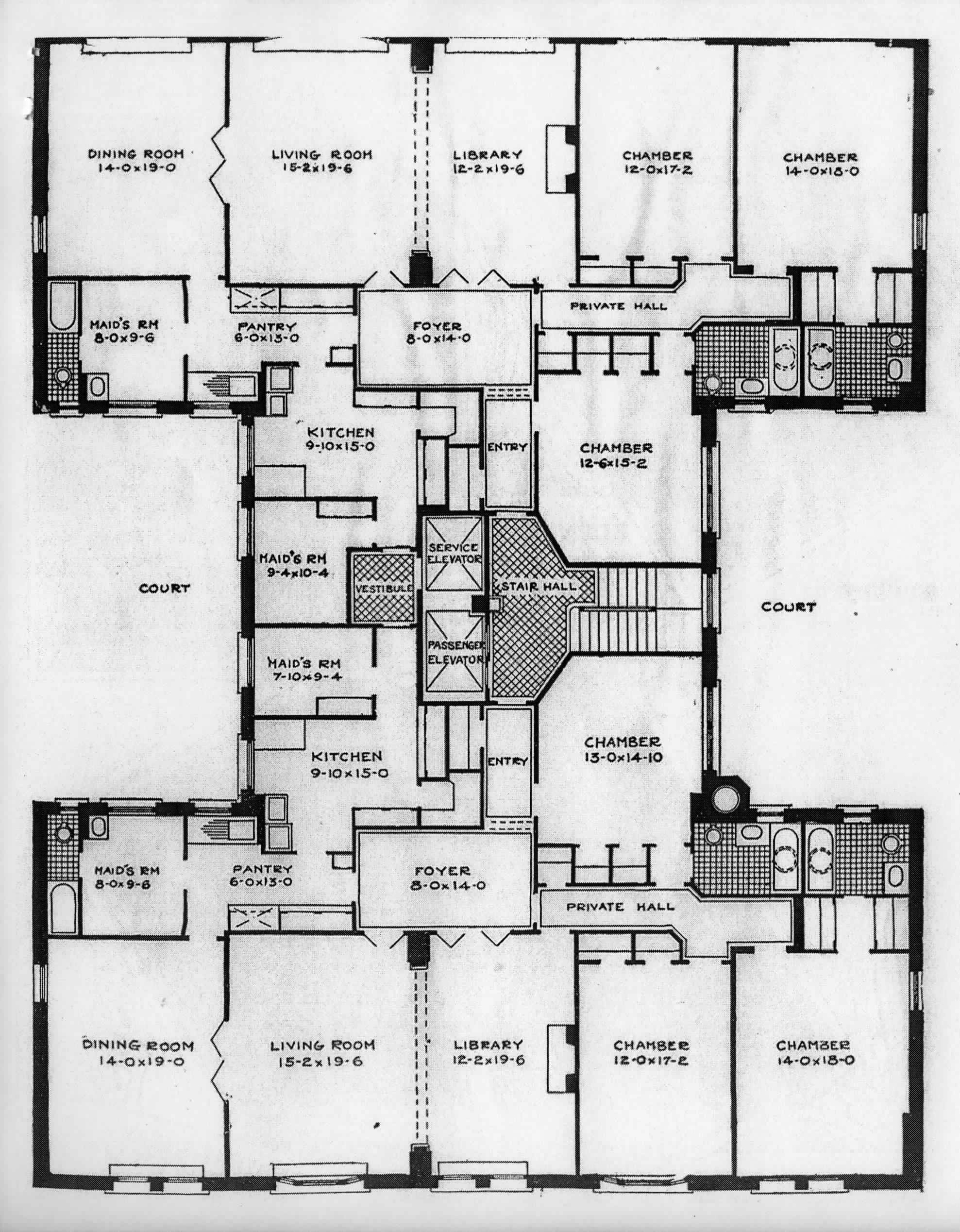

Residents would enjoy all the space and amenities of a private home. There were just two sprawling apartments per floor. An advertisement in 1913 boasted that The Wellwyn sat on a “park thoroughfare” on a “select private house block.” It described the apartments as having “nine extra large rooms, grouped about foyer and entry; 3 baths, pantry and ample closets.” The living rooms measured 27 by 19 feet.

At a time when most upscale apartment buildings had a telephone on the ground floor managed by a switchboard operator, The Wellwyn featured an “interior telephone system.” Service elevators went directly to the kitchens and there were “extra servants’ rooms, laundries and storage rooms for each tenant” in another part of the building.

The New York Herald noted that the passenger elevators “open into small central halls leading to both apartments on every floor. All the suites have central foyers and five outside main rooms. Above the fourth story all rooms are outside [i.e., have windows], because private houses of lower heights adjoin the building.”

The tenants were understandably well-to-do and most had country homes. When The Sun reported on the upcoming marriage of Rosamond Beck to Oscar Bachrack, for instance, it noted that the groom was “of 260 West Seventy-second street and Toronto, Canada.”

Le Roy and Ruby T. Brewster were well-known in Upper West Side society. They moved into The Wellwyn from a mansion on West End Avenue. Their summer home was in Scarsdale, New York. Hugo Jaeckel signed a lease in September 1919. He was the principal in Jaekel & Sons furriers on Union Square with a branch office in Leipsig, Germany.

Depending on the floor, in 1922 rents in The Wellwyn ranged from $4,000 to $5,200 per year. The more expensive amount would equal about $6,600 per month by today’s standards. The building was sold in 1937 and five years later was reconfigured. The capacious suites were divided so that there were now three or four apartments per floor. At the same time a two-apartment penthouse, unseen from the street, was added.

Among the colorful residents in the second half of the 20th century were Ernest and Jean Everly McChesney. Ernest had started his career singing on Broadway and in 1931 became one of the featured artists in the Ziegfeld Follies. From 1954 to 1960 he was the principal tenor with the New York City Opera. After his retirement, he taught voice for years at the Manhattan School of Music.

Ernest had started his career singing on Broadway and in 1931 became one of the featured artists in the Ziegfeld Follies.

Jean McChesney’s career was no less interesting. She had been secretary to the world-famous operatic contralto, Ernestine Schumann-Heink. She then became an assistant to theatrical impresario Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel. The New York Times pointed out that Jean McChesney helped Rothafel “in preparing for the opening of the Radio City Music Hall in 1932.”

Another notable resident was interior designer Tice Alexander who lived here with his partner, Glenn Albin. After having worked with Parish-Hadley Associates, Alexander struck out on his own in 1986 forming Tice Alexander, Inc. headquartered in his apartment in The Wellwyn. He wrote a monthly column for Connoisseur magazine. On August 27, 1993, The New York Times reported, “Tice Alexander, an interior designer in New York who was known for the elegance of his rooms, died on Monday at New York Hospital. He was 35.” He had fallen victim to the currently rampant AIDS epidemic.

The Wellwyn’s sedate gray brick and white limestone façade is nearly unchanged since it elbowed its way among the private mansions along the block more than a century ago.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

260 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Meet Max & Don Lawrence!