Barefoot Yoga in a Shoemaker’s House

by Tom Miller

On April 2, 1892 the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported “Lamb & Rich are preparing plans for four modern dwellings, which J. R. Stimpson will erect on the north side of 72d st.” The 25-foot wide residences were designed as two distinctively different pairs. 251 and 253, faced in brownstone, were much more sedate than their brick-clad neighbors at 247 and 249 with their tall crocket-topped gables. It may be that included in Stimpson’s contract with the architects was partial ownership. Lamb & Rich held title to two of the completed structures, including 251.

Phoebe Palmer Knapp lived in a Brooklyn mansion described by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1889 as “historic” owing to the Knapps’ many distinguished guests including Generals Sheridan and Grant and “famous statesmen, Jurists and soldiers.” The Knapp family was in Paris in the summer of 1891 when Joseph F. Knapp became so ill it was decided to rush home. Knapp, who was the president of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company died on the steamship while at sea.

On January 28, 1894, soon after the 72nd Street row was completed, The New York Times reported that Lamb & Rich had traded Phoebe Knapp’s Brooklyn mansion for the “handsome four story brick and stone front dwelling, 251 West Seventy-second street.”

The wealthy widow did not remain here especially long. She sold it to Charles Emerson Bigelow and his wife, the former Isabella Lyall Dean, in September 1900 for $60,000 (or about $1.9 million today). Phoebe Knapp moved to a suite in the Hotel Savoy.

The Bigelows had been married in Isabella’s parents’ home on March 14, 1893. When they moved into the 72nd Street house they had two children of their own, six-year old Dorothy and four-year old Emerson. Another child, Lyall Dean, was Isabella’s son from a former marriage.

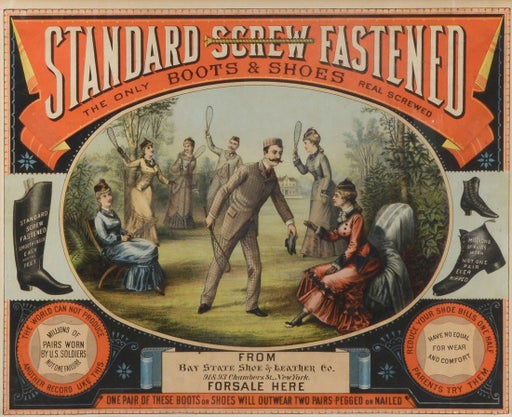

Born in Brooklyn in 1851, Bigelow’s ancestors arrived in America in the 17th century. He had entered his father’s firm, the Bay State Shoe and Leather Company three days after he graduated from Yale. In 1879, he was made president of the company.

War frequently put wedding plans on a fast track, often disregarding the formality of the announcement of engagements. Later that year, on November 3, Brooklyn Life reported “Announcement has been made of the marriage of Mr. Emerson Bigelow, U.S.N.R.F….who is stationed at Newport, R.I.” The apparently hurried ceremony had taken place in the home of his bride, Marian Fuestman, on West 86th Street the week before.

The Bigelows’ summer estate, The Knolls, was in Norfolk, Connecticut. Society columns reported on their annual coming and going as the two residences would be opened or closed for the season. During the winter season the 72nd Street house was the scene of social events, like the reception Isabella gave in January 1902. Brooklyn Life listed the five other women in the receiving line.

Lyall Dean graduated from Yale, his stepfather’s alma mater, in 1909. His engagement to Helen Stearns was announced in November 1912. It was a rather long engagement, with the wedding in the fashionable St. George’s Church on Stuyvesant Square not taking place until November 3, 1915. Among the large wedding party was Dorothy, who was an attendant, and Emerson, who stood as his half-brother’s best man.

Between Lyall’s engagement and wedding Isabella focused on Dorothy’s introduction to society. On November 29, 1913 Form, An Illustrated Weekly reported that the Bigelows would be giving a reception on December 6 “to introduce their daughter, Miss Dorothy Bigelow.”

In 1917, immediately upon graduating from Yale and with war raging in Europe, Emerson joined the United States Navy Reserve Force. War frequently put wedding plans on a fast track, often disregarding the formality of the announcement of engagements. Later that year, on November 3, Brooklyn Life reported “Announcement has been made of the marriage of Mr. Emerson Bigelow, U.S.N.R.F….who is stationed at Newport, R.I.” The apparently hurried ceremony had taken place in the home of his bride, Marian Fuestman, on West 86th Street the week before.

War would not prevent the Bigelows from formally announcing Dorothy’s engagement to Ward Melville the following year. The fact that the groom-to-be was working in the office of the Army’s Quartermaster General in Washington D.C. meant that there was little chance of his being deployed to Europe. Nevertheless, it was a short engagement. It was announced on April 18 and the couple was married two weeks later.

By now, West 72nd Street was no longer the quiet, residential district it had been in 1900. The avenue-wide street had become a busy thoroughfare and many of the private homes were being converted to apartments and stores. With their children gone, the Bigelows left the commodious house. On August 16, 1919 the Record & Guide reported they had leased it to Abraham Garfein “for business.”

Charles E. Bigelow initiated a renovation for his tenant. Completed the following year it resulted in a “dwelling for two families and non-housekeeping apartments.” The seemingly confusing description meant that there were now two apartments with kitchens and several others where no cooking was allowed. The stoop had been removed and the entrance lowered to the former basement level.

Among the first tenants were Alexander S. Vale, his wife, Rhea, and their six-year old daughter. Vale was an architectural engineer who earned the equivalent of $76,500 today. But there were troubles in the Vale household. The Daily News reported on June 24, 1920 that Vale “described the wife as a ‘pleasure-loving woman’ who had caused her husband…to live beyond his means.”

When the money ran out, Rhea sued for divorce. In court Vale’s attorney said, “He tried to hold this pleasure-loving woman by using part of a trust fund, of which his mother is a trustee, which he must now pay back.” Rhea was reportedly also involved with a married man in Far Rockway. The judge gave custody of the child to her father and granted no alimony to the pleasure-loving mother.

On February 19, 1923 he pled guilty to “bucketing” and was sentenced to 18 months in Sing Sing Prison. Bucketing was the term for brokerage fraud, by which a broker would mislead his client regarding the purchase of stocks.

An advertisement in 1921 described “three rooms, 25×25, bath, kitchen, every modern convenience and privacy.” The rent was $160, or in the neighborhood of $2,300 per month today.

Another tenant who appeared in the newspapers for the wrong reasons was Ezra Reed Vail. On February 19, 1923 he pled guilty to “bucketing” and was sentenced to 18 months in Sing Sing Prison. Bucketing was the term for brokerage fraud, by which a broker would mislead his client regarding the purchase of stocks.

A month earlier tenant Joseph Tierney had driven his automobile onto the Staten Island Ferry. His car was the first in line to drive off and as the boat pulled into the slip, 24-year old Peter Simpson stepped in front of the car. The proprietor of the terminal’s restaurant and candy stand, he was apparently in a hurry to disembark. Suddenly the ferry “came to a sudden stop,” according to the Perth Amboy Evening News on January 17. The article continued, “before the driver could apply his brakes, [the automobile] struck the man and pinned him between the chain and the car.” Tierney drove the injured man to the hospital in his car.

Performer Sunya Shurman operated the Shurman School in Carnegie Hall above the Ballet Arts in the 1940’s. By 1955 she had opened the Shurman Center in at 251 West 72nd Street. On June 29 that year, for instance, The New York Times reported “Priyagopal, the Hindu dancer who taught at the famous Tagore school and is said besides to be the only exponent in this country of the Manipuri style, is giving a series of studio recitals under the auspices of Sunya Shurman at the Shurman Center.”

By 1962, the Academy of Mental Sciences operated from the address. That year it offered the new book Auto Suggest You Can Use, by hypnotist Joseph Lampel for $2.50. Sharing the commercial space at the time was a much different tenant, Design Knitting. The store offered “astonishing yarns, over 5,000 patterns” and free expert instruction so a novice could “create designer sweaters at a fraction of the price!”

The second floor was home to Gryphon Record Shop for more than a decade, starting around 1991. And, in 2010 the Prenatal Yoga Center operated from the building. Rather amazingly, much of Rich & Lamb’s interior detailing survives on the upper floors after more than a century and a quarter.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

251 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 251 West 72nd Street:

Meet Melanie Wesslock!