Looking for Gothic Surprises

by Tom Miller

As the construction industry recovered following the Financial Panic of 1873, interest in the Upper West Side renewed. It was helped along by the opening of the Ninth Avenue elevated train. Architects created fanciful rows of upscale homes that drew on a variety of historic styles.

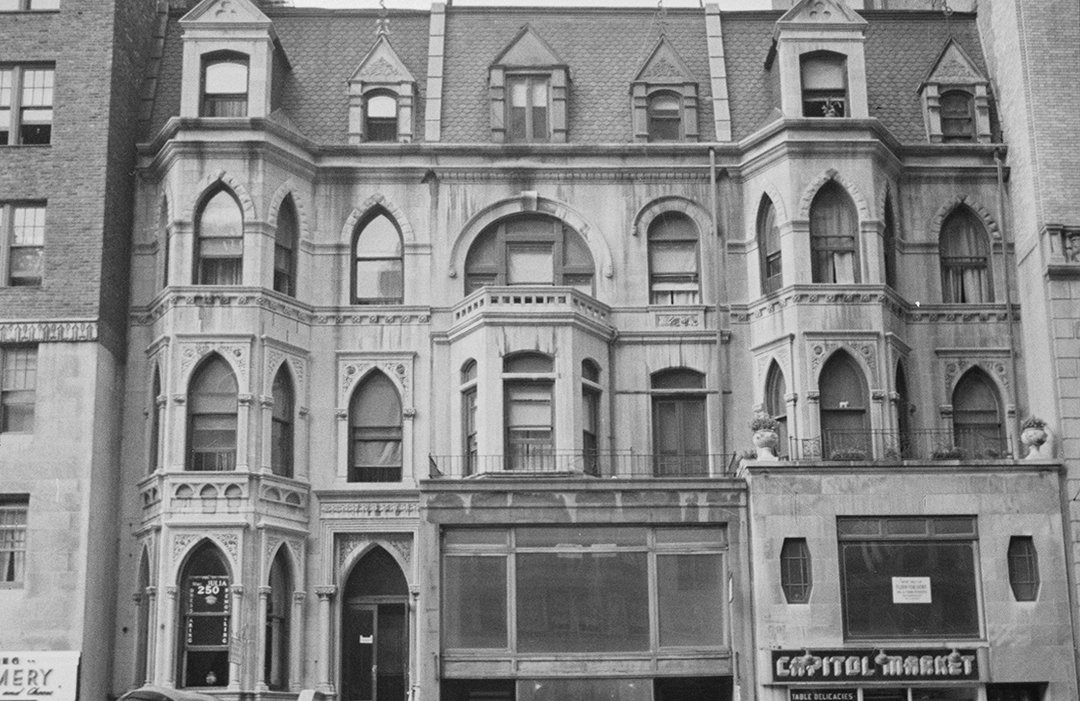

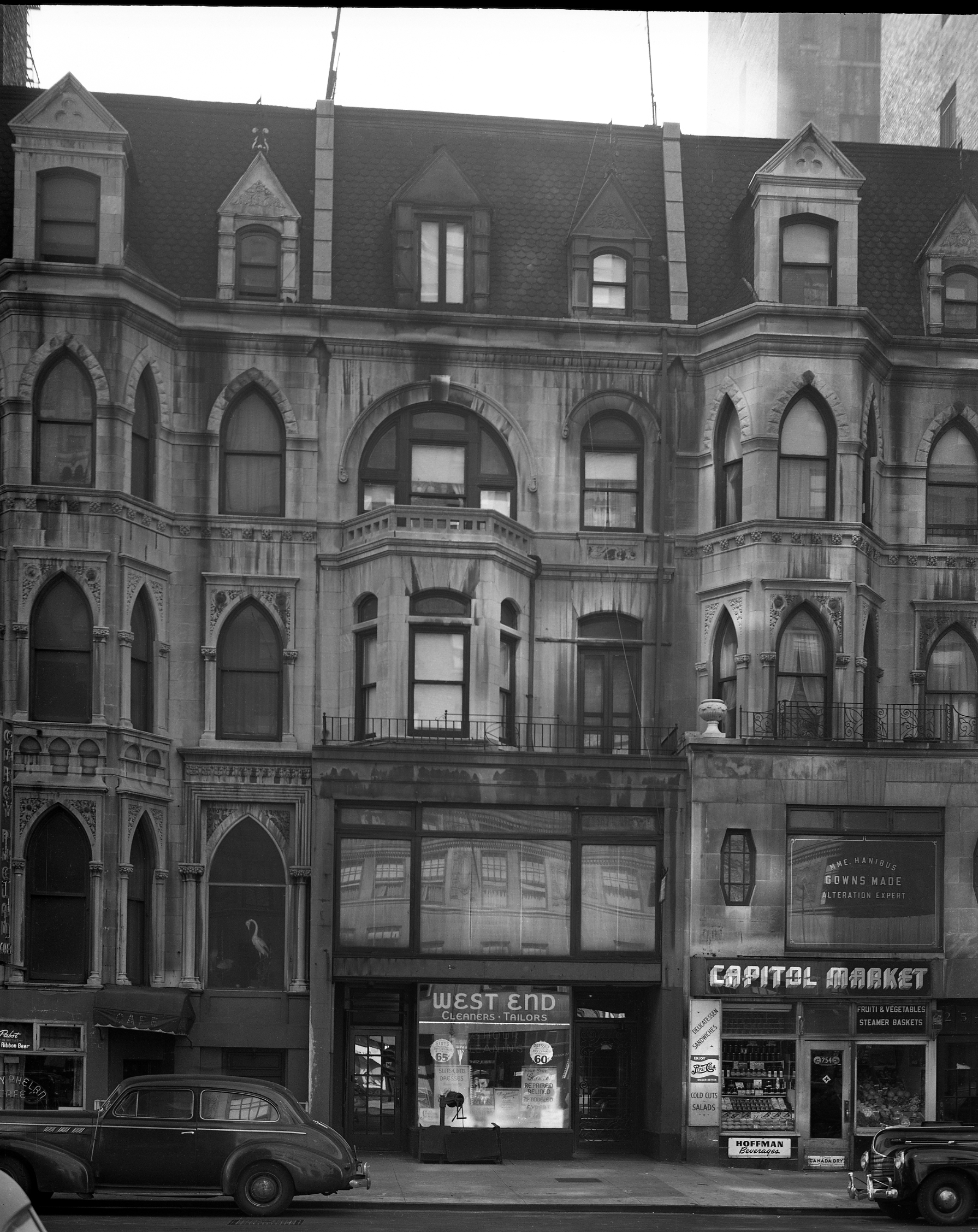

Among the most unusual were the six four-story residences designed in 1887 for developer Michael Steinhart by architect George F. Pelham. Completed in 1888 the row was a fanciful interpretation of the Gothic style. The limestone facades were carved with near-ecclesiastical ornamentation. Steep stone stoops rose to the elaborate entrances above the English basements. Above it all: high mansard roofs, covered in fish scale tiles, provided a full fourth floor.

Within the first decades of the 20th century, half of the delightful row would be razed for the Upper West Side’s next craze—the apartment building. But numbers 250 through 254 survived.

The upscale owners included the Michael O’Brien family, who lived in number 252 by 1895. With O’Brien and his wife, Elizabeth, were son Michael; daughter Loretta and her husband Nicholas J. Cosgrove. On January 24 that year, Michael and Elizabeth hosted a dinner “on the occasion of the first anniversary of the marriage of their daughter, Mrs. N. J. Cosgrove.”

The dinner was held at the Hotel Majestic and among the 25 guests were the entire bridal party of the year before. “The tables were profusely decorated with roses,” reported The New York Times. The anniversary parties would become a tradition in the O’Brien household. The following year it included a theater party followed by supper at the Park Avenue Hotel.

The warm tradition came to an end in 1900. On June 23, Loretta and Nicholas took a car to the pier where the steamer Monmouth was docked. They were on their way to Point Pleasant, New Jersey to select a cottage for the summer.

Nicholas Cosgrove had been a manager in an importing house, but resigned because of heart trouble. As they exited the car, they realized that the Monmouth was about to pull away. They ran to the boat, barely catching it.

“Mr. Cosgrove had not made three steps on the boat when he gasped and fell dead on the deck,” reported The New York Times the following morning. A relative expressed indignation to reporters. “He said that when Mr. Cosgrove fell dead the Monmouth was still tied to her pier, and that instead of bringing the body ashore at once it was taken to the Highlands, accompanied by Mrs. Cosgrove, who was almost prostrated by the shock.”

Next door to the O’Briens, at 254 West 72nd Street, John Mulford and his family were living by 1894. Mulford was President of the Mutual Benefit Ice Company, purchasing agent of the New York Central Railroad, and Vice President of the West Side Bank. When he died at the age of 74 on Friday, March 18, 1898, he still held his position with the bank. His funeral was held in the house two days later at 3:00.

Police explained that it was “her custom to engage board at a fashionable hotel or boarding house, and there entertain her friends. In each case, it is alleged, she would leave the place with her bill unpaid.” Despite the large amount of money in her possession, Sophie Smith had racked up a long list of debts.

Louisa Mulford and her two grown children continued to live in the house. On May 21, 1901, she placed an advertisement in the New-York Tribune. “Wanted: Protestant cook, washer, and ironer in family of three adults; city references.”

In 1894, while numbers 252 and 254 were still rather grand private homes, Number 250 was already being operated as an upscale boarding house by “Mrs. Morse.” Her boarders came from the upper crust, like Frederick McKay. On June 20, 1894, The Times notified social page readers that he would “spend the Summer at Larchmont.”

Mrs. Morse rented rooms the following year to Mrs. Sophie Craig Smith, described by The Times as “forty-nine years old, a stylishly dressed woman.” On October 10, 1895, Sophie (who also went by the name of Mrs. F. N. Gill) was arrested as she prepared to take passage on a steamship to Europe.

Police explained that it was “her custom to engage board at a fashionable hotel or boarding house, and there entertain her friends. In each case, it is alleged, she would leave the place with her bill unpaid.” Despite the large amount of money in her possession, Sophie Smith had racked up a long list of debts—including $18 to Mrs. Morse for unpaid rent.

The enraged charlatan “declared that she would bring suit against the persons who had caused her arrest, as the delay in sailing for Europe had seriously deranged her plans.”

Another well-do-to boarder of Mrs. Morse was Mrs. J. W. Dullea who was robbed by Lawrence Macy in 1895. Lawrence Macy confessed to robbing 14 other women, as well, when he was apprehended after “a long chase on the roof of a house in the Elizabeth Street Precinct,” according to The Times on August 7, 1895. The total value of the loot was estimated to be around $5,000.

At 252 West 72nd Street, the O’Briens remained on well past the turn of the century. Loretta Cosgrove filled her time dealing in real estate, and Joseph was by 1907 a member of the New York Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. Michael O’Brien, now widowed, died in the house on Friday June 2, 1916. His funeral was held in the parlor the following Monday.

The O’Briens’s long-time neighbor, Louisa Mulford, had died at the age of 76 on July 16, 1909. At the time of her death, the house was valued at $60,000—in the neighborhood of $1.6 million today. Following her death, the servants were kept on for two months as caretakers at their regular salaries. Among these was Mabel Cavanagh, recently hired as a chambermaid.

Two years later the family received a shock. Mabel Cavanagh filed suit against the estate. She claimed that Louisa had “provided that for the rest of her life Miss Cavanagh was to have an income from the estate of $13 a month and the exclusive use of a bedroom in the Mulford house at 254 West Seventy-second Street and the general use of the dining-room, sitting-room, laundry and kitchen, as had been her privilege while Mrs. Mulford lived.” If that were impossible, she would settle for a lump sum of $16,000.

The estate’s attorney, George W. Carr was skeptical at best. “Mrs. Mulford was a very methodical woman and she was most cautious in all her business dealings,” he said. “It is past human belief that she would enter, without consulting her business advisers, upon any such agreement, and that, too, with a domestic who had been in the household for only a month.”

Cavanaugh and her attorney no doubt knew that it was impossible for her to live in the house at this point. In August 1910, before the messy affair arose, the estate had leased 254 West 72nd Street to the Hawthorne School. The day school for privileged girls, which was operated “under English and French supervision,” had already moved into number 250 in 1906.

Among the students at the Hawthorne School in 1910 were 17-year old Margaret Sumner, the daughter of attorney Edward A. Sumner, and Elise Shearman, daughter of the Vice President of W. R. Grace & Co., L. H. Shearman. That year the Sumners were summering on the family yacht, the Kiaroa, at Huntington, Long Island; and the Shearmans were in Garden City.

On Monday, August 29, 1910, Elise’s mother drove her to Huntington to visit Margaret Sumner. With a friend on board, Margaret rowed a boat from the yacht to pick up Elise at the Huntington Club house. When the small boat returned to the yacht, Margaret caught hold of it with a boat hook and instructed Elise to climb up the ladder. The treacherous ebb tide was running as Elise slipped and fell fully dressed into the waters.

While Mrs. Sumner ran for a life buoy, Margaret Sumner plunged into the bay after her schoolmate. “Miss Sherman could not swim and also was hampered by an automobile veil which was wound tightly over head, neck, and shoulders. She was helpless and was being carried swiftly away by the tide,” reported The New York Times.

In the meantime, the girl still in the rowboat “knew little about rowing and was too frightened to do anything but scream.”

The courageous Margaret Sumner, trained in life saving, caught Elise and held her as she tried to swim against the tide. The girls were carried several hundred feet out; but Mrs. Sumner had managed to throw the life buoy and Margaret held onto it until the girls were pulled in.

The Times reported “Both were exhausted but otherwise little the worse for the wetting. As soon as she had rested Miss Shearman was able to return to Garden City.”

The 1913 term would be the last for the Hawthorne School in 250 and 254 West 72nd Street. In 1914 when Mary Geer leased 250 to A. H. Paynter, it was referred to by the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide as a “four-story private dwelling.” Number 254 West 72nd Street would remain in the possession of Louisa Mulford’s estate until 1920 when it was sold to a realty company. It, too, was described as a four-story dwelling at the time.

But as the Depression years neared, the homes were converted to apartments and their stoops removed. In 1928, a store and office were installed on sidewalk level of 252. Above, there was now one apartment per floor. Dancer and showgirl Georgia Gray (whose real name was Lucia Dickens), lived here in 1931. The Times described her as “about 25 years old, red-haired and of unusual beauty.”

Georgia’s friends were less than respectable and in January 1931, she wrote to her grandmother in Augusta, Georgia asking for money to return home. She explained that she was “tired of the crowd I am running with.”

Before she could leave, however, she was subpoenaed as a witness in the murder investigation of Vivian Gordon. Vivian was to testify against Patrolman Leigh Halpern, a vice-squad member; and against his partner, Daniel Sullivan; but she was murdered before she could testify.

While Mrs. Sumner ran for a life buoy, Margaret Sumner plunged into the bay after her schoolmate. “Miss Sherman could not swim and also was hampered by an automobile veil which was wound tightly over head, neck, and shoulders. She was helpless and was being carried swiftly away by the tide,” reported The New York Times.

Halpern’s trial came first. Prosecutors charged him with perjury, saying that he and Sullivan “used stool-pigeons and testified as the arresting policemen in women’s court that they did not know the men.” On the stand, Georgia testified, “that she was a friend of Harry Gibson and Monte Booth, fugitive stool-pigeons, and that Halpern, Sullivan, and another plain clothes man, Eddie Butler, had visited her home…with the two stool-pigeons.”

Before Sullivan’s trial began, Georgia became suddenly ill. Around on Friday night, March 13, 1931 she left number 252 West 72nd Street for Bellevue Hospital. At around 10:30 the following evening she was dead.

Georgia’s body was found not in her hospital bed, but on the floor beside it. The Deputy Medical Examiner, Thomas A. Gonzales, did an autopsy and deemed the death “natural.” Assistant District Attorney Daly was less sure. He told a reporter “the woman came to him several weeks ago, a few days after a jury had acquitted Patrolman Leigh Halpern, formerly of the midtown vice squad, of perjury and told him she feared ‘friends of Halpern and the police would bother’ her.” A poison expert was called in.

In 1933 opera director Maurice Frank and his family leased an apartment in at 250 West 72nd Street. Since 1930, he had directed the open-air opera held at the Polo Grounds. On June 20, 1933, his 16-year old daughter, Bernice, went missing. The Washington Irving Evening High School student was fascinated with the stage; so her father put the word out to the managers of small stock companies to search their troupes for her. Newspapers reported “Miss Frank weighs 120 to 125 pounds, has bobbed brown hair, brown eyes, is five feet six and one-half inches tall. She wore a brown dress and a small hat.”

On July 9, she had still not been found and The New York Times reported “The girl’s mother, Mrs. Florence Frank, has been ill since her daughter disappeared.” It was not until September 13 that a wire from Hollywood, California arrived at the Times’ desk.

“Held in custody as a juvenile run-away, Bernice Frank…was picked up today by local authorities.”

Bernice told officials she had run away because she did not want to attend business college. She took $250, dyed her hair red, and rode to California on a bus. Once in Hollywood she took on the name Margot Eaton and tried (without success) to land a job as an extra in motion pictures.

The telegram ended “The girl was recently ejected from her room for failure to pay rent.”

This section of West 72nd Street was undergoing change and the tenants in the three Gothic houses reflected it. The same year that Bernice Frank ran away Harry Lewis, who also lived in number 250 was arrested for the 18th time. Three years later another tenant, 44-year old Carey Phelan was arrested for assaulting female golf pro Bea Gotlieb. In 1942 Benjamin “Fat Benny” Goldstein was indicted in a bootleg case, charged in a $3 million conspiracy case and with selling 190-proof alcohol. Patrick H. Lennon, who used the alias “Harry Hoffman” was arrested for fraud in 1955.

The renters in the other buildings were similar. Harrison H. Hayes Wentworth lived in number 254 in 1933. Formerly connected with Universal Picture, Inc. he was also once the casting director for the Norma Talmadge Production Corporation. But now he was charged with stealing $5,000 in jewelry from author Gilbert Patten and “with obtaining money from several prominent persons, including an Assistant United States Attorney, by telling them stories of his misfortune or selling them a share in a $200,000 estate he says he owns in Maine, but which the police believe is purely the object of his imagination.”

Eventually things turned around. By 1972, 250 was home to West Side, an art gallery. In 1973 W. M. Tweed’s, a bar, operated from the sidewalk level. Rose-ann Quinn was drinking there one night that year when she met a man who lived across the street at number 253. Rose-ann’s decision to go to his apartment that night was fatal. She was stabbed 14 times and her murder was the inspiration for the novel and movie Looking for Mr. Goodbar.

In 1996 The Sugar Bar was opened in number 254 by Nickolas Ashford and his wife Valerie Simpson—the recording artists Ashford & Simpson. The couple lived in apartment #1A here.

Although the lower two floors of numbers 252 and 254 have been lost, the parlor floor of 250 West 72nd Street remains relatively intact. Just look up for the delight of the once marvelous Gothic rowhouses.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

250-254 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 250-254 West 72nd Street:

Meet Susie Cheng!

Meet Michelle and Willi!

Meet Nicole Ashford!