The Kate E. Morgan House

by Tom Miller

In the 1890’s Hugh Lamb and Charles Alonzo Rich, partners in the architectural firm of Lamb & Rich, often doubled as developers–purchasing property, and then designing and erecting speculative structures themselves. Such was the case in 1894 when they broke ground for an upscale residence at No. 243 West 72nd Street, just east of West End Avenue.

The properties along the street were being rapidly developed at the time. By 1888, there were already 60 high-end homes along West 72nd Street, culminating at Central Park West with the hulking and fashionable Dakota apartment building. Lamb & Rich designed No. 243 in the Renaissance Revival style; with its four stories above the high English basement clad in warm orange brick and trimmed in terra cotta. The high stone stoop led to the entrance within a rounded bay that rose to the fourth floor, where it provided a balcony above a terra cotta cornice. The top floor openings were flanked by panels of terra cotta where charming babies’ heads peered from swirling foliate decorations.

By the time the 20-foot wide residence was completed in the spring of 1895 it appears Lamb & Rich already had a buyer. On April 6, Charles Rich sold his half to Hugh Lamb for $35,000 and on May 1, Lamb sold the house to Catherine Martin Elsworth Morgan for exactly twice that amount. The price would equal just over $2 million today.

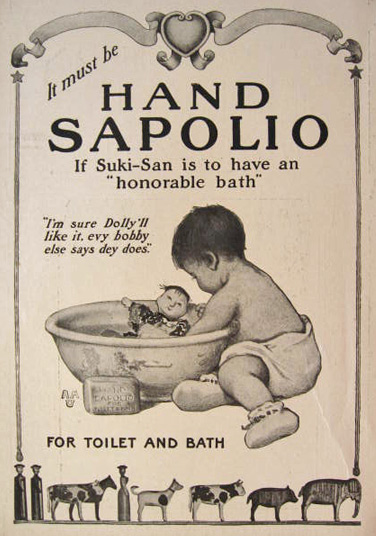

Catherine was known among society as Kate E. Morgan. She was the daughter of Edward and Phebe Ann Elsworth and the widow of John Williams Morgan, who died in 1881 at the age of 46. Morgan had been president of the soap-making firm, Enoch Morgan’s Sons Company, founded by his father. John and Kate had had six children; but four of them died in infancy or childhood. Moving into the new house with their mother were 29-year old Albert John and his 16-year old sister, Katherine.

Albert, who was by now a member of Enoch Morgan’s Sons, was more visible in society than his mother. He filled the library in the new house with his extensive collection of rare 19th century books. An avid sportsman, he was described by The Official Golf Guide in 1901 as “a prominent golfer,” and owned the luxurious yacht, the Viator. So lavish was the yacht that in 1899 The Social Register listed it as the family’s summer address. In February 1898 the New York Athletic Club Journal wrote of him:

There are few members of the New York A. C. better known than Mr. Albert J. Morgan. For years scarcely a day of the winter season has passed without his spending several hours in the clubhouse, while in the summer many members of the Club have been his guests on the cruises of his yacht Viator. In business circles Mr. Morgan is well and favorably known as a member of the firm of Enoch Morgan’s Sons.

Just a year after that article, one of those summer outings on the Viator ended horribly, with one guest dead. In August 1897, Albert took a party of guests for a cruise along the coast of Maine. Among those on board were Walter Sherman Baldwin, a 43-year old “man about town,” Henry Barnet, and Roland Burnham Molineux. Both Barnet and Molineux, like their host, were wealthy bachelors and members of the New York Athletic Club. Also on board was the beautiful Blanche Chesebrough.

Albert John was an avid sportsman, described by The Official Golf Guide in 1901 as “a prominent golfer,” and owned the luxurious yacht, the Viator. So lavish was the yacht that in 1899 The Social Register listed it as the family’s summer address.

All three men seem to have been smitten with the young woman. According to Harold Schechter, in his The Devil’s Gentleman, Blanche described the yacht’s “deep-seated, gaily cushioned deck chairs drawn forward on the polished decks. Awnings softened the intense light of mid-day.” She said that a steward presented a silver tray bearing small sandwiches, caviar and champagne. “We drank the iced Moët & Chandon, its liquid amber like gold…There was gaiety and lightheartedness and laughter, for happiness was abroad that brilliant summer’s day.”

Blanche also remembered that all three men flirted with her; Morgan, for one, nestling closely up to her while chatting. It was a dangerous flirtation. Shortly after the outing ended both Barnet and Morgan became seriously ill. Barnet died and for some days, it appeared that Morgan, too, would succumb. The initial diagnosis for both was typhoid fever.

A week after Barnet’s funeral Molineux, the only one of the three suitors not to be stricken with the mysterious disease, married Blanche. A chemist–or druggist–by profession, he had access to deadly chemicals and, as it turned out, he was not a man to be crossed. In 1898, after he became engaged in a feud with Harry Seymour Cornish, the athletic director of the Knickerbocker Athletic Club, he mailed a bottle of Emerson’s Bromo-Seltzer to Cornish’s attention at the club. Molineux had mixed the medicine with cyanide of mercury.

Tragically, Cornish took the bottle home that night. The following morning, December 28, his 62-year old cousin Katherine Adams was suffering a headache. Cornish mixed the bromo-seltzer with water and gave it to his aunt. She died shortly after the doctor arrived.

Now the death of Henry Barnet and the near-fatal illness of Morgan were given closer scrutiny. Barnet’s body was exhumed and found to contain the same poison that killed Katherine Adams. As the details of the murder trial were reported by the press, the incidents of the 1897 cruise were evoked. On February 9, 1899, the Evening Telegram’s headline read “Inquest Opens with Mystery” and included a large picture of the Viator. The caption read “The poison yacht Viator.”

Three days later The New York Times reported “Albert J. Morgan, the owner of the yacht Viator, is indignant at the way his name has been used in connection with the case. He said that he proposed to bring proceedings without delay against the newspapers which had published unfounded charges against him.”

Morgan was not bluffing. On March 3, The Fourth Estate reported “James Gordon Bennett, proprietor of the New York Herald and Evening Telegram, has been made the defendant in a suit brought by Albert J. Morgan to recover $100,000 for an alleged libel.” That amount would be in the neighborhood of $3 million today.

As a side note, the guilty verdict of Molineux was overturned because the prosecution had used the poisoning of Barnet–an unrelated and unproven crime–as evidence. One week after his subsequent retrial and acquittal Blanche filed for divorce on the grounds of mental cruelty. Two months later, she married her divorce attorney.

With the ugly affair behind them, the Morgans continued on among society. In 1900, Albert held a dizzying list of memberships that included the Racquet and Tennis, the St. Nicholas, Colonial, Grolier, Manhattan, New York Yacht, Larchmont Yacht and Atlantic Yacht Clubs and the Aldine Association, along with, of course, with the New York Athletic Club.

On February 28, 1901, the New-York Tribune noted that the evening before “Mrs. Kate E. Morgan had a theatre party of twelve at the Lyceum Theatre, taking her guests home to supper after the play.”

At the time of the party, Albert was preparing to liquidate his library of nearly 1,000 volumes. On March 2, The New York Times reported “The fine collection of nineteenth century rarities formed by Albert J. Morgan…was privately sold on Wednesday of this week to George H. Richmond, the dealer in rare books. The sum paid for the library was said to be $60,000.” (Or about $1.75 million today.)

Richmond quickly resold the books. “Mr. Richmond has recently printed an attractive catalogue of the Morgan books,” wrote The Times on June 29. Already he had sold “the magnificent Kipling set” to George M. Williamson for $6,000. The article again detailed Albert’s library, noting, for instance, that “The Morgan Tennysons are remarkably complete,” and concluding “It is a pity that Mr. Morgan decided to sell his collection, and one also regrets that it was sold privately.”

Albert may have liquidated his collection in anticipation of his upcoming marriage and subsequent move from the 72nd Street house. On April 25, 1902, he married Jessie L. Flint. The Morgan women, 67-year old Kate and 23-year old Katherine, were now alone with their servants.

In 1881, the year that Kate’s husband died, her niece, Fannie A. Elsworth, had married real estate operator Du Bois Smith. The Smith family replaced the Morgans in No. 243 West 72nd Street around 1910. The couple had four children, Malcolm, who was in business with his father, Edmund, Josephine and Dorothy.

On January 9, 1915, the National Courier noted that Malcolm’s engagement to Helen Le Roy Miller had been announced. The article mentioned that he was a member of the esteemed St. Nicholas Club and of Squadron A. The New York Times added “The Smiths spend most of their time at the family homestead, Mills’ Pond [at Smithtown, Long Island]…and when in town live at 243 West Seventy-second Street.”

Both Fanny and Du Bois had died before 1924. By then West 72nd Street, once an exclusive residential thoroughfare, had seen the incursion of commerce. Handsome homes were either demolished or converted for business. 243 survived more-or-less intact for a time, operated as an unofficial “apartment house” owned and managed by Arthur B. Daveney in 1928.

The 70-year old Daveney was arrested in February that year when a tenant in another apartment house, Sylvia Toro, filed assault charges. On Friday, February 10, he had knocked on her door at 4 West 93rd Street to collect the rent. According to Sylvia, when he realized she was alone, he attacked her. As reported by The Times, “When she resisted, she said he hurled her against a wall, snatched up a large bread knife and threatened to kill her.” She further said she broke away and fled to the apartment next door, where music teacher Minna Lee Beene gave her shelter and called a doctor.

Daveney left the building and proceeded on to 243 West 72nd Street where he was later arrested. In court, he pleaded not guilty and gave a starkly different account of that afternoon. He told the judge Sylvia had told him she did not have the rent, and then “became hysterical and ran out of the room.” Nevertheless, her evidence was convincing. “She produced a dress in court that had been slashed and exhibited a deep scratch on her arm and three bruises on her left leg.”

The 70-year old Daveney was arrested in February that year when a tenant in another apartment house, Sylvia Toro, filed assault charges. On Friday, February 10, he had knocked on her door at 4 West 93rd Street to collect the rent. According to Sylvia, when he realized she was alone, he attacked her. As reported by The Times, “When she resisted, she said he hurled her against a wall, snatched up a large bread knife and threatened to kill her.”

Among Daveney’s tenants in 243 West 72nd Street at the time were Ignatz Friedman and his wife. Born in Hungary in 1865, he had been a naturalized citizen for 40 years. He had been in the meat packing industry for decades and was a well-known figure in the business.

Around the same time, the basement level was converted for business–what The New York Times called in September 1930, “an alleged speakeasy.” Working there was 29-year old bartender Bernard J. Flanly, who lived on West 123rd Street with his wife, Marion. The couple were in the news on September 30 after a nasty altercation in that apartment building.

Very late on the night of Friday September 12, Bernard was visiting the apartment of James and Mabel Liebling. Marion Flanly finally would wait no longer and stormed up to the Lieblings’ apartment and demanded that her husband come home. A loud quarrel ensued, which prompted another tenant to call the police. An officer “restored peace,” according to The New York Times, “but while the participants were going down in the elevator the quarrel was renewed and Flanly struck the operator.” All four ended up in the West Side Court on September 19.

A commercial conversion was inevitable and it came in 1935 when the stoop was removed and the facade of the former basement and parlor levels was pulled out to the property line. A restaurant was installed at street level, offices and one apartment on the second floor, and two apartments each on the upper floors. When real estate operator Harry Spingarn purchased the property in February 1943, it was described as a “five-story apartment building, containing small suites.”

Among the tenants in 1946 was 23-year old Lewis Warner, a meteorologist. But after he was hired by the U.S. Army that year, he got himself into serious trouble. He was working in Allied-Occupied Berlin when he was arrested in August for the illegal trafficking of goods. On November 25, he pleaded innocent before an Army court-martial on charges of black-marketing and unlicensed trading. The military brought forth two witnesses to establish “that he was working as a weather observer for the Army when he was arrested by its criminal investigation division last August.”

The New York Times reported that among the four charges against him, “One charge states that he conspired with three brothers and his father, David Warner of New York City, to engage in unlicensed export-import business and ‘used his presence in the European theatre to gain commercial advantage.'”

The ground floor restaurant was converted to retail space in 1951. In the mid 1950’s the second floor office was home to Music Service. Its ambiguous ads in Popular Mechanics read simply “Songwriters! Send poems, songs.” One wonders what happened to the lyrics or if the senders got ever were paid.

Whitney Blake, music publishers, had taken over the office space by 1958. And, by 1970 it was home to the Park River Real Estate office. In the meantime, at least one upstairs tenant was on the wrong side of the law.

Among the nine gangsters who were indicted by a Federal grand jury in Philadelphia on October 31, 1963 was 54-year old tenant Anthony Stassi. The men were charged with “shark racketeering.” Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy announced “the case involved the lending of money to three businessmen and threats to beat them when they were unable to meet payments.”

Home to the B. I. Rosenhaus & Sons linoleum store in the 1990’s, the ground floor today houses a dry cleaning shop. The upstairs office is now The Paint Place, offering painting classes. Few busy passersby pause to look above The Paint Place’s second floor where three floors of Kate E. Morgan’s handsome rowhouse survive; a relic of a more genteel period in West 72nd Street history.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

243 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 243 West 72nd Street:

Meet Marci Freede!