View of 242 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

A Life-Changing Phone Call

by Tom Miller

John W. Noble, Jr. and his brother, William, were both involved in real estate development on the Upper West Side by the mid-1880’s. The two would eventually join forces as William Noble & Co. around 1898 however, they occasionally worked on projects cooperatively well before that. That seems to be the case with the row of houses on the south side of West 72nd Street, between West End Avenue and Broadway begun in 1886. Only John W. Noble was officially listed as the owner prior to construction, but when the finished residence at 242 West 72nd Street was sold in 1888 to Alonzo E. Conover, it was William’s name listed as seller.

The brothers’ architect, William Harloe, had designed the four-story and basement house in the Renaissance Revival style. A high stone stoop led to the entrance. The upper floor windows were framed in quoins and an elaborate pressed metal cornice capped it all. Conover paid $45,000 for the house—just over $1.25 million in today’s money.

Conover and his wife, the former Philena Rebecca Underhill, had one daughter, Clarrie, who was 17 years old when they moved in. Conover was a partner in J. S. Conover & Co., which produced “art mantels, grates, tiles, open fireplaces, andirons, tongs, shovels, brasswork of every description for household decoration, plates and high art metal work generally,” according to The New York Times on January 1, 1886.

The Conovers remained in the house only a few years, selling it in February 1892 to George E. Woolsey and his wife, the former Edith Delancey, $47,000. The couple had one son, Floyd E. George Woolsey was the principal in the Hammond Distilling Company, a manufacturer of whiskey.

Among Woolseys’ live-in staff were Amanda Anderson and Hulda Lindstrom. Police arrived at the West 72nd Street house on April 7, 1899 and arrested the 18-year-old Hulda. According to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, she was charged with “taking a savings bank book and $30 in cash from a trunk belonging to Amanda Anderson. The two girls were friends.” One assumes it was the end of that friendship.

The end of the line of 242 West 72nd Street seemed imminent when the Hasco Building Company purchased it in 1916.

The Woolseys only occasionally were mentioned in the society pages. An exception was on June 1, 1900, when the New-York Tribune reported, “Mrs. George L. Woolsey gave a dinner party last evening at her home…in honor of Miss Mabel F. Leaman and Dr. Fielding T. Robeson, whose marriage is to take place at the Hotel Majestic on Tuesday next.”

Floyd E. Woolsey was described by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle as “a prominent young Manhattanite.” He was married to Gladys Bell Balch on October 16, 1909, “in the front drawing-room of her home” on Monroe Place in Brooklyn Heights. The newspaper reported, “Close to a hundred people were present at the ceremony; for the reception that immediately followed 900 had been invited.”

In 1910, only a few months after the wedding, the Woolseys leased 242 West 72nd Street to “Miss P. Hapley-Pembrey.” By 1913 it had several well-to-do boarders. That year Albert P. Case was living here when he and two investors incorporated the I. S. Van Loan Railway Equipment Company, Inc. Mr. and Mrs. Myron Augustus Lockman also occupied rooms in the house.

In September 1914 the Woolseys sold their former home to the Reivax Realty Co., Inc. It was again leased as a private house, now home to Walter Danford Geer, his wife, Mary Wiley Geer, and their four children. Mary introduced Helen Danforth Geer, to society at a tea in the drawing room on the afternoon of November 24, 1915. The New York Press noted, “A dinner and theatre party will follow.”

At the time of Helen Geer’s debut, West 72nd Street was noticeably changing as apartment buildings and shops replaced the former private residences. The end of the line of 242 West 72nd Street seemed imminent when the Hasco Building Company purchased it in 1916. The Record & Guide reported, “The buyers own the four adjoining houses at 244-250 West 72d street…[The plot] will be improved with an apartment house.” But something derailed those plans and 242 West 72nd Street was resold to John J. Sweeney, who altered the interiors into small apartments and offices. He advertised the building to let in August 1917, describing it as:

Four story, reconstructed, 18 rooms, 11 bathrooms, steam heat, hot, cold water each room, electricity; parquet floors; especially arranged physicians’ studios, bachelor apartments, private school.

Among the tenants in 1919 was Edward P. Myers, described by Commerce and Finance on September 3 as “a staid, mild-mannered man, 52 years old, a broker, and lives at 242 West 72d street, New York.” But that demeanor had changed a few days before the article. Myers went into a drug store on Manhattan Avenue to make a phone call. According to the proprietor, when he entered the telephone booth, “he was a perfect gentleman, if you were to judge by appearances. He was fashionably dressed, had a rose in his buttonhole, wore a sweet smile, carried a gold-headed cane and bowed courteously.”

All Myers wanted to do was to call an associate at a hotel regarding an appointment. He deposited his nickel, gave the operator the number, then waited. And waited. Commerce and Finance said, “after waiting fifteen minutes he decided to put another nickel into the slot. After waiting another twenty minutes, he alleged the operator asked, ‘Number, please.’” He demanded to talk to a supervisor. He explained to her how long he had waited. She hung up.

Before Myer raged out of the booth, he ripped the receiver out of the telephone and “left it on the floor with the wires torn and broken.” Then, according to Harold Bleicher, an employee, “he used such heated terms of speech that he blistered the kalsomine on the drug store walls.” The magazine said, “His face was red and he spouted maledictions upon various persons, meanwhile brandishing vigorously his gold headed cane.” The mild-mannered Edward P. Myers was arrested on a charge of malicious mischief.

In 1929 John J. Sweeney embarked on even more sweeping renovations to the former house. The stoop was removed, and a store installed on the ground floor. The second floor now held dentists’ offices and the upper floors were divided into furnished rooms. The store became home to the Broadway Star Market, and the following year Estelle Rosen’s beauty parlor took one of the intended dentist offices.

Estelle became a hero of sorts in January 1931. Isidor Sisselman was a serial rapist, described by the Daily News as the “strong-arm Don Juan of Brooklyn.” The 32-year-old was married with a child and worked for a painters’ union. On various nights he would tell his wife he had to be out on union business, then rent a car (newspapers called them “drive-it-yourself-cars” because they had no chauffeur) and seek victims. The Daily News said, “The roughneck lover, according to police, went on marauding expeditions three nights a week.”

Isidor Sisselman was a serial rapist, described by the Daily News as the “strong-arm Don Juan of Brooklyn.”

Dressed fashionably, he would lure young women into the automobile, then beat and rape them, stealing their jewelry and money before letting them go. Although arrested seven times, he was never convicted because of the victims’ “reluctance to reveal their shame,” according to the newspaper. That changed when he picked Estelle Rosen as a victim. The Daily News said she “fought off Sisselman and escaped from him after a furious battle.” She then rushed to police and “described the drive-it-yourself car and the brigand Romeo in detail.” Undercover cops haunted the rental car agencies until Sisselman turned up. He was arrested and charged with attacking 25 women.

In 1936 the former grocery store became the upholstering and interior decorating shop of Bernard Silver. In the mid-1950’s one of the second-floor offices was home to Eddie Gay’s gag shop, which did a great deal of its business in mail order.

The first years of the 1970’s saw a tailor and dry-cleaning shop on the ground floor and in 1971 the upper floors were converted to two apartments each. The rents ranged from $255 to $280 (about $1,750 in today’s money for the most expensive).

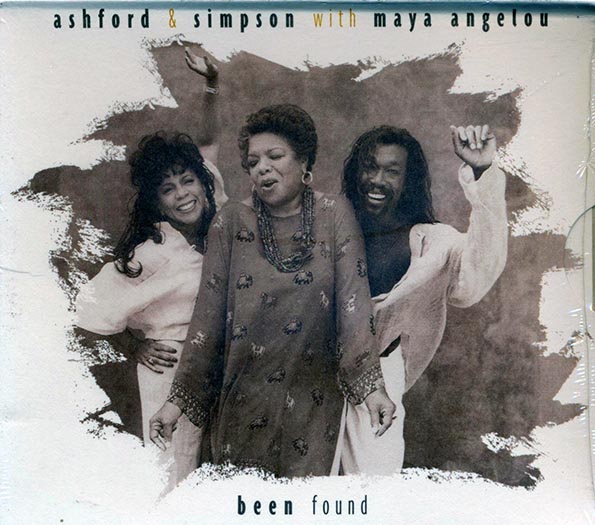

In 1996 the husband-and-wife songwriting and production team Ashford & Simpson opened Sugar Bar here. They hosted open mic events on Thursday nights, when performers like Queen Latifah, Vicki Natalie, and Felicia Collins sang. It was here where poet Maya Angelou recorded her album Been Found in 1996.

Throughout the month of August 1999 singer Melba Moore gave a one-woman show, “Sweet Songs of The South” in Sugar Bar. Newsday said she “shares her life’s struggle through sons and recollections” through the show.

In March 2002, following the announcement of their engagement, entertainment columnist Liz Smith took Liza Minelli and David Gest to the theater. Afterward, according to Smith, “I went home, but Liza and David continued on to Ashford & Simpson’s Sugar Bar on 72nd Street, where I hear Liza sang and won standing ovations.” The destination spot remained in 242 until recently, replaced by a window treatment store.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

242 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 242 West 72nd Street: