Parlor Takes a Bow

by Tom Miller

On January 29, 1886 architect William Harloe filed plans for five four-story brick and stone houses on the south side of West 72nd Street, between Broadway and West End Avenue. Each of the 20-foot-wide homes would cost the developer, John W. Noble, $20,000 to construct—or about $561,000 in today’s money.

Among the row, completed in 1887, was 238 West 72nd Street. As with the others, a high brownstone stoop led to the parlor floor. Decorative carvings crowned the window lintels, and the ambitious pressed metal cornice included a wide frieze with ornate panels.

It was sold to Judge Leo Charles Dessar and his wife, Sadie. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio and educated at the Columbia College Law School, he was admitted to the bar in 1870 and appointed to the bench in 1885. He was, as well, the president of the Fulton and Cortlandt-Street Ferry Railroad Company. The couple had two daughters, Constance and Amy Grace. The family’s summer home was in Long Branch, New Jersey.

In 1902 Dessar hired architect George W. Wood to design a two-story bay window at the parlor and second floor that engulfed the entire width of the house. Its grouped windows would have flooded the interior with natural light. A significant alteration, it cost the equivalent of $46,000 today.

In 1902 Dessar hired architect George W. Wood to design a two-story bay window at the parlor and second floor that engulfed the entire width of the house.

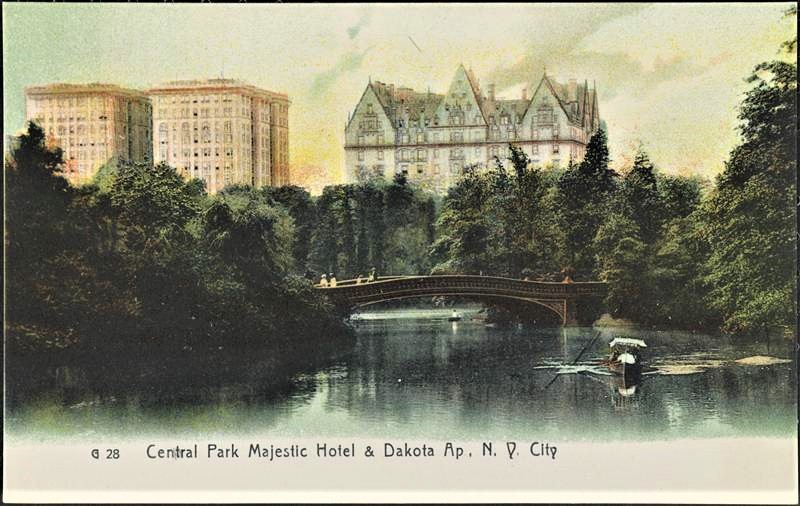

Constance Dessar was married to Jay Spiegelberg in Sherry’s (Sherry’s was, like Delmonico’s, a prestigious society restaurant-caterer) on November 25, 1908. It was a large event and the wedding party included a dozen ushers from some of the city’s most prominent Jewish families. The New York Times advised that after their six-week honeymoon in California, the couple would live at the Majestic. (The upscale Majestic Hotel sat on Central Park West at the corner of 72nd Street, across from the Dakota. Its replacement, the Majestic Apartments, were built in 1929.)

In 1913 Amy graduated from Barnard College. That joy soon turned to sorrow when her mother died on September 17. Sadie left her entire estate of around $1.5 million by today’s standards to her husband. The New York Times reported, “Upon his death, she directed that her estate be divided equally between her two daughters.”

Leo Dessar announced Amy’s engagement to Charles Arnold Rohr on June 2, 1917. The Sun noted, “Miss Dessar, who is a graduate of Barnard College, is interested in many charities in this city and Long Branch, where she spends her summers.” The couple was married a month later July 6.

Tragically, on October 10, 1918, only three months after her first wedding anniversary, Amy’s funeral was held in the West 72nd Street house. She was just 27 years old.

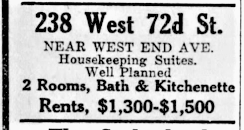

By now West 72nd Street, which had been an exclusive, upscale residential neighborhood when the Dessar family moved in, had become increasingly commercial. Leo C. Dessar immediately left 238 West 72nd Street and within the year, it had been converted to “apartments of two exceptional rooms and kitchenette with bath,” according to an advertisement. The ad touted the “modern alterations.” Rents for the apartments ranged from $1,300 to $1,500 per year—or about $1,800 a month today.

Although small, the apartments rented to respectable professionals, like civil engineer George H. Clarke, and prominent theatrical agent Lea Herrick and his wife, the former Florence MacGuire. Upon Herrick’s death in 1922 the New York Herald noted he “had developed many notable figures in the musical comedy field.”

Tragically, on October 10, 1918, only three months after her first wedding anniversary, Amy’s funeral was held in the West 72nd Street house. She was just 27 years old.

Also living here at the time was Mrs. Robert Westford Allen, sister of stage star Lillian Russell. Her apartment caught fire on November 20, 1923 and the Daily News reported, “A portrait of the late Lillian Russell, the actress, valued at $7,500 was destroyed yesterday” in the blaze that “ravaged” the apartment. “Other valuable portraits in the studio of Mrs. Allen also were burned, and damage totaled to $20,000.”

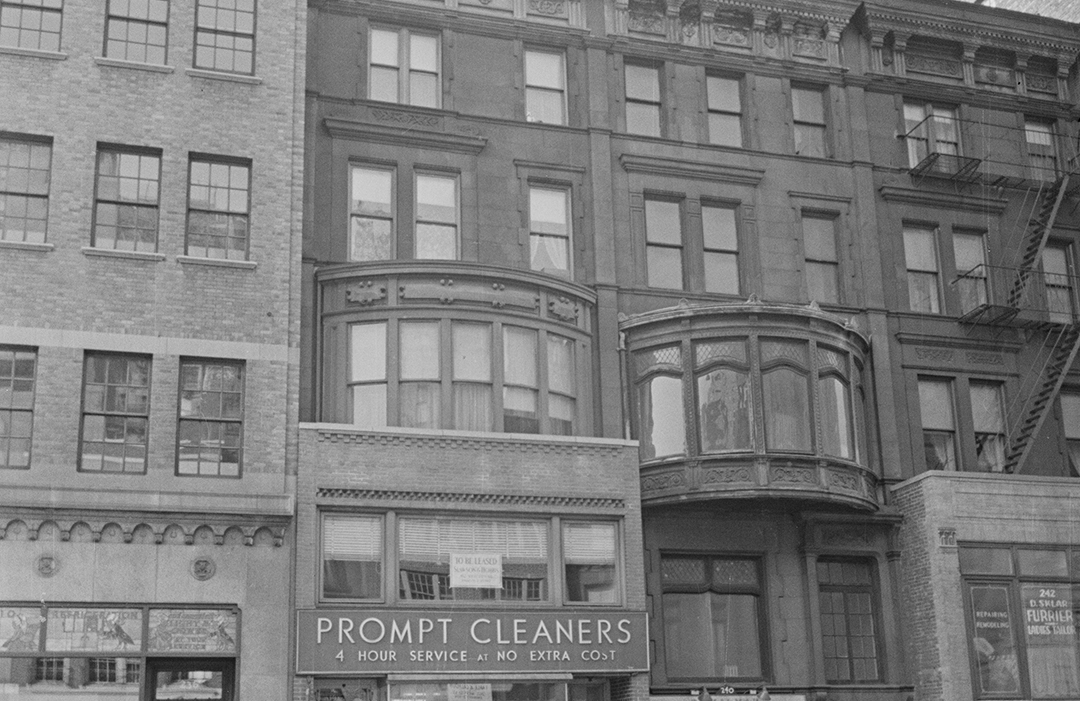

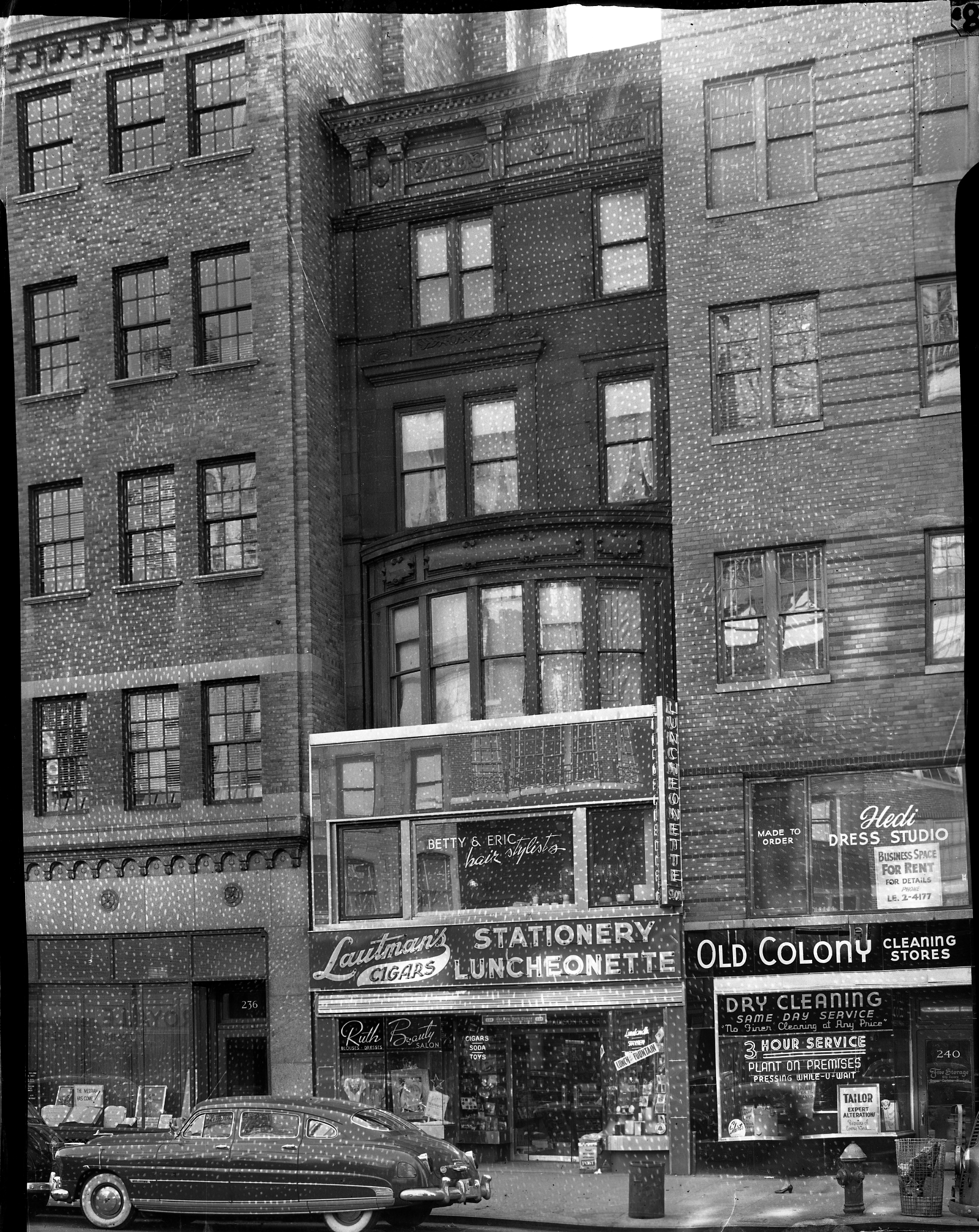

A more significant alteration by the architectural firm of Murgatroyd & Ogden was completed in 1937. It resulted in the lower two floors being converted to business and the upper floors renovated to accommodate two apartments each. The stoop was removed, and a two-story brick storefront was installed.

For two years the store was home to a beauty parlor. In 1939 P. Wender signed a long-term lease for his dry-cleaning establishment, Prompt Cleaners. It was a neighborhood fixture for years. By 1973 The Other Woman, a women’s fashion store was in the space.

Although beleaguered, the upper portion of the once-stately Dessar home survives rather intact—a reminder of a far different era along the block.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

238 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 238 West 72nd Street:

Meet Bruce Markow!