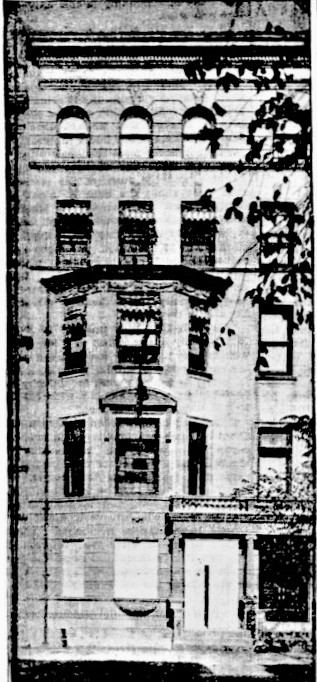

View of 237 West 72nd Street from south. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

A Rare Holdout for Rare Books

by Tom Miller

In 1895, the real estate development firm of Chas. Beuk & Co. began construction on a row of four high-end houses on West 72nd Street, between West End Avenue and Broadway. They were designed by the firm’s in-house architect, Henry F. Cook. Unlike so many high-stooped homes in the neighborhood, Cook designed these as “American basement” residences—with entrances just above the sidewalk.

Two of them—235 and 237 West 72nd Street—were designed as a pair—with a shared portico and balcony, and identical fourth and fifth floor designs. A three-story faceted bay distinguished 237.

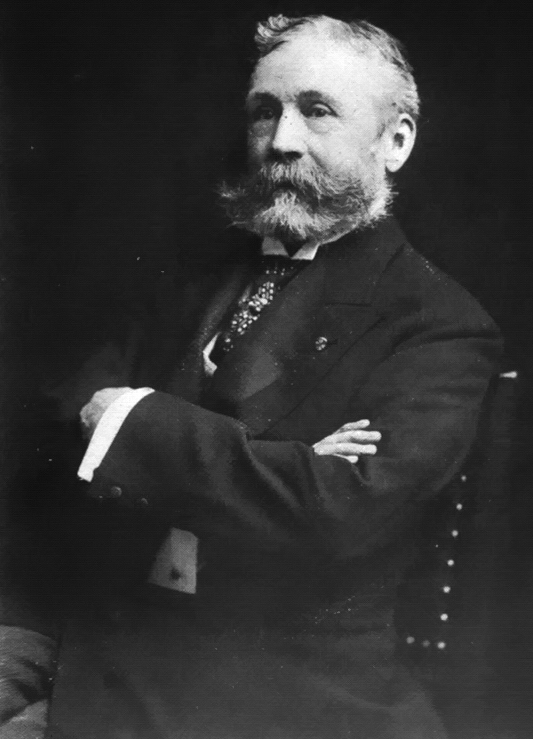

In April 1896, Charles Buek sold the 23-foot-wide house to George Clinton Batcheller for $70,000—around $2.23 million in today’s money. Born in Massachusetts in 1834, the millionaire traced his roots in America to Joseph Batcheller, who landed in Salem, Massachusetts in 1636. His wife was the former S. Ada Cummings.

Batcheller was the founder and sold owner of G. C. Batchellor & Co., a corset manufacturer. He was, as well, president of the Crown Perfumery Company of London, Paris and New York, and of the Connecticut Steel and Clasp Company. His corset factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut employed more than 1,000 workers and turned out 6,000 corsets daily.

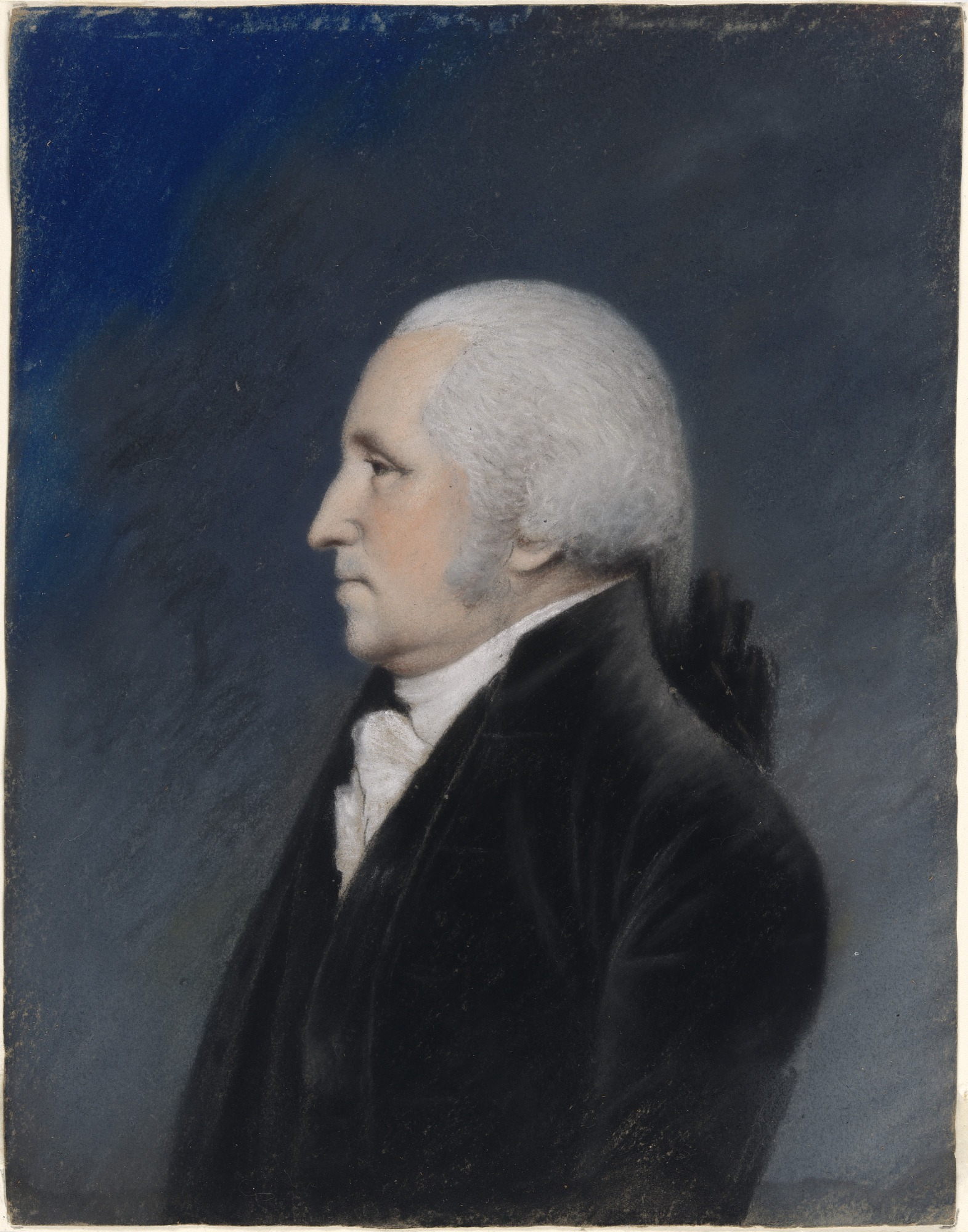

The couple filled the house with rare books and paintings. The 1898 Batchelder, Batcheller Genealogy said, “In his collections are the rare and valuable portraits of Gen. George Washington and Martha, his wife, taken at Mount Vernon in 1796 by [James] Sharples, the London artist…He has a literary turn of mind, and though fond of society, yet devotes much of his leisure hours to his library, which contains many miscellaneous and standard works by the best authors.” In fact, an entire floor of the 72nd Street house was devoted to his rare book collection.

When the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia was threatened with demolition in 1899, George Clinton Batcheller purchased the property for $25,000. He presented it to the Betsy Ross Memorial Association to become a museum.

The childless Batchellers often hosted houseguests. On October 7, 1897, for instance, The New York Press reported, “Mr. and Mrs. George Clinton Batcheller of No. 237 West Seventy-second street have as their guests Mrs. Albert F. Wheaton, Jr., Mrs. William S. Miller and daughter and Miss Alice Louise Miller of Boston.

When the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia was threatened with demolition in 1899, George Clinton Batcheller purchased the property for $25,000. He presented it to the Betsy Ross Memorial Association to become a museum.

On the evening of April 29, 1900, the author and publisher Miriam Leslie, known professional as Mrs. Frank Leslie, called on the Batchellers. Her coachman waited in her brougham in front of the house. At some point, a hansom cab was going west along 72nd Street, when part of the harness snapped. The horse became frightened a “dashed across Columbus ave. toward the Boulevard [Broadway] and Riverside Drive,” reported the New-York Tribune. The galloping horse swerved just as he neared Mrs. Frank Leslie’s expensive vehicle and the hansom smashed into it. Her coachman, John West, was thrown to the pavement.

The panicked horse kept going, finally being stopped by a policeman at Riverside Drive. “The cab was scratched,” said the New-York Tribune, but the Leslie brougham was badly wrecked. The upsetting episode brought an abrupt end to Miriam Leslie’s evening with the Batchellers. “Mrs. Leslie had her brougham and team sent home, and sent West to his home. Then she was driven to her own home in a cab,” said the article.

Ada Bacheller died in 1901. The following year, on July 27, 1902, the New-York Tribune reported, “George Clinton Batcheller…sailed last week on the Oceanic for a tour of the Continent. On his return he will open his camp at Rangely Lake, Maine.” (Beginning in the 1890’s, it was fashionable to have either a “lodge” or a “camp.” Lodges were in the mountains and camps were near lakes. Life at neither had the slightest similarity to wilderness camping.)

Bacheller continued to host houseguests. On October 2, 1909 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “Dr. Lyon G. Tyler, president of William and Mary College of Virginia, is a guest of Colonel George Clinton Batcheller…Dr. Tyler is a son of John Tyler, who was president of the United States from 1840 to 1844.”

In 1913, George C. Batcheller surprised society by remarrying. The New York Times reported on September 18 “Miss Truene Ruth Geddes and Col. George Clinton Batcheller were married yesterday in Boston, Mass. Col Batcheller is a widower and first met Miss Geddes last season at Palm Beach. He is well known in social and business circles here and throughout the country.”

Some believed that Truene was either merely a trophy wife, or a gold-digger. According to The Washington Times, she was “pronounced the ‘most perfect woman in Newport.” The article pointed out that George had “seventy-nine years to his credit,” while “his beautiful bride” was nearly 50 years younger.

On January 24, 1915, George Clinton Batcheller was “seized with a chill.” The Daily Long Island Farmer noted, “He had just completed arrangements to go to Palm Beach with his wife this week to spend the winter.” He died in the West 72nd Street house two days later. His funeral was held in St. Andrew’s Church on West 76th Street on January 27.

Truene lived on in the house, alone with her staff. The inheritance left to her by George (she got everything other than some charitable bequests) was evidenced in a piece of jewelry she lost on October 17, 1916. When she arrived at the Manhattan Opera House that night, the bar pin on her cloak was still there. Sometime after going later to the Biltmore Hotel and then to the Vanderbilt Hotel, she realized it was missing. She placed a notice in the New York Herald that read:

A Tiffany bar platinum Pin, two pear shaped and one round diamond, lost Tuesday. Five hundred dollars reward at 237 West 72d.”

The reward—equal to more than $12,000 today—might have been successful had she not told a reporter that the pin “is valued at $2,600”—more than five times the reward.

Some believed that Truene was either merely a trophy wife, or a gold-digger. According to The Washington Times, she was “pronounced the ‘most perfect woman in Newport.” The article pointed out that George had “seventy-nine years to his credit,” while “his beautiful bride” was nearly 50 years younger.

In 1918, Truene married William Edward Spencer of Great Village, Nova Scotia. She relocated to Canada and leased the Manhattan house. While mansions along West 72nd Street were quickly being razed or converted to business at the time, 237 West 72nd Street survived unchanged as a succession of well-to-do families came and went.

In 1934, Truene leased the house to the Amsterdam Democratic Club. The organization hired the architectural firm of Lowinson & Podaro to make interior alterations for a clubhouse, with a single apartment on the top floor. The club remained until 1944 when Truene Spencer sold it “in its first change of ownership since 1896,” as noted by The New York Sun on November 22. The article added that the house “is to be altered into apartments and stores.”

The renovation resulted in a store on the ground floor, a club (most likely still the Amsterdam Democratic Club) on the second, an office on the third, and one apartment each on the upper floors.

At mid-century, the ground floor was home to the Chapel Eternal Star, led by its pastor, Rev. Rose Ann Erickson. The church held a “Bazaar Social” on September 15, 1956, to which Rev. Erickson announced, “Come and bring a friend.”

The last decade of the 20th century saw the Royale Pastry Shop in the space. The New York Times food critic Florence Fabricant reported on July 15, 1998, that the shop “bakes heavy, moist and dense two-pound domes of Eastern European corn rye, often called corn bread…For some, this chewy bread is the ultimate Jewish rye bread, but it is not for the faint of heart, especially when slathered with chicken fat.” Today a weight loss center occupies the space.

Above the ground floor, George Clinton Batcheller’s house—where an entire floor was dedicated to rare books—is relatively intact.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

237 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 237 West 72nd Street:

Meet Marc Wigder!