View of 235 West 72nd Street from south. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Caught in a Fog

by Tom Miller

In April 1881 architect Henry F. Cook partnered with real estate developer Charles Buek to form Charles Buek & Company. The firm would design and erect dozens of houses and apartment buildings throughout the city, many of them on the burgeoning Upper West Side. In 1895, it began construction on four high-end rowhouses on West 72nd Street between West End Avenue and Broadway. Completed the following year, they were designed as American basement houses, which forewent the high stoops that were quickly falling from fashion.

Two of them, 235 and 237 West 72nd Street, shared a short porch separated by a stone railing and an entrance portico that provided a balustraded balcony to the second floors. The rusticated limestone base of 235 upheld three floors faced in planar stone. The fifth floor, identical to that of 237 West 72nd Street, returned to a rusticated face broken by three arched windows.

Charles Buek & Company sold 235 to Gardiner Sherman and his wife, the former Mary M. Ogden. The president of the Seventh National Bank, Sherman was born in New York City in 1840, and had graduated from New York College in 1859. He was a direct descendant of Roger Sherman, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

He and Mary were newlyweds, having married on June 16, 1896. Sherman’s first wife, Jessie Gordon, had died on July 15, 1884, nine days after the birth of their daughter, Jessie Gordon Sherman. The family would remain in the house until 1903 when they sold it to Eugene Vallens. Only a year later he resold 235 West 72nd Street in 1904 to Edmund Arthur Stanley Clarke and his wife, the former Louisa Hall Ward.

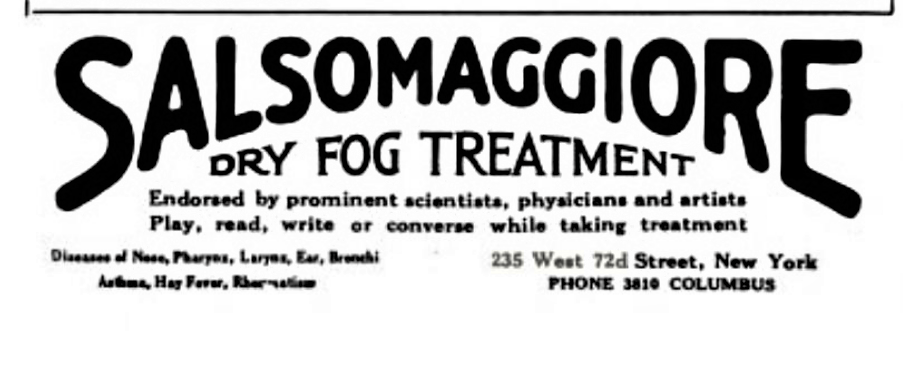

Dominco installed the Salsomaggiore Dry Fog Treatment Institute in the house.

The millionaire engineer was president and director of the Scranton Mining Co., the Lacakwanna Steel Co., the Corsica Iron Co., the Hobart Iron Co., the Tilly Foster Iron Mines and several other related firms. He and Louisa had two children, Marion Montague and Louise Clarke. The Clarkes remained here until 1911 when they leased it to a succession of wealthy tenants. Mrs. Florence L. Patterson lived here until 1913 when Mrs. J. E. Morris signed a lease. Her daughter, Eliza G. Morris drove a Simplex automobile in 1914. The following year the house was leased to Antonio D. Dominco “for a term of years.”

Dominco installed the Salsomaggiore Dry Fog Treatment Institute in the house. An advertisement in the 1916 Report of The United States Hay Fever Association said that the “recent discovery” of the Dry Fog Treatment of Hay Fever was under the auspices of the Italian Government and was “patronized regularly by the Greatest Artists in the World.”

Although the treatment sounds like quackery today, it was taken seriously at the time. The Institute’s president was Spanish operatic bass Andres de Segurola, its honorary president was famed tenor Enrico Caruso, and on its board of directors was Italian operatic baritone Pasquale Amato.

On the night of May 25, 1917, the directors hosted a reception in the mansion. The Sun reported that guests were “invited to submerge into the fog room” and said, “The orchestra was playing the national anthem when, as the guests emerged from the fog room, Dr. Sarlabous announced that he was prepared to drink their health with them in the institute’s banquet hall.”

Dr. Emilio Sarlabous was the attending physician at the institute. He explained that the dry fog room “is credited with bringing the curative powers of the air in Salsomaggiore, the Italian village, to New York.” The “fog” was not composed of water droplets, but tiny particles of dust. The Sun continued, “The dust is supposed to be so annoying to the hay fever germ as to cause it to abandon its victim and make off to pleasanter climes.”

Later that year, on September 30, reporters were called “to the dry fog works in a fancy four story house at 235 West Seventy-second street,” as worded by The Sun, to hear an announcement. Andreas de Segurola asserted that “patriotism, pure patriotism” had prompted the press conference. He announced that 20,000 American soldiers suffered from hay fever. “Here is the sure hay fever treatment,” said De Segurola, “and the cure is free for every man in the soldier uniform of Uncle Sam who comes into 235 West Seventy-second street.”

For those who did not have an Army uniform, the price was $3 per treatment, $25 for ten, and $50 for 25. The cost for the 50-treatment bundle would equal about $1,000 today.

The Institute remained in the former mansion until 1919 when it was purchased by the New York Bridge Whist Club. On March 29, 1919, The Sun reported that the club had paid $60,000 “for its new home.” The amount was the equivalent of nearly $900,000 in today’s money. Incorporated in 1907, the New York Bridge Whist Club was one of several social clubs beginning in the early 1890’s that were formed specifically for playing cards.

“There are three prerequisites to membership, namely, the applicant must be a gentleman, must play a good game of bridge, and be passed upon by the card committee.”

A report of the United States Board of Tax Appeals said that in 1919 the club had about 200 members. It noted, “There are three prerequisites to membership, namely, the applicant must be a gentleman, must play a good game of bridge, and be passed upon by the card committee.”

The Board of Tax Appeals had been looking into the club because “the uniform stake of the club is 2 cents per point.” Happily for the club, the decision rendered was “the game of auction bridge as played at the New York Bridge Whist Club is not gambling…but is purely a game of skill.”

The club remained until 1932 when the Amsterdam Democratic Club took over the house. Little of the mansion changed, inside or out, until a renovation completed in 1953. It resulted in a funeral parlor on the first and second floor, a duplex apartment on the third and fourth, and one apartment on the fifth. A new one-story façade replaced the original, including the handsome columned portico.

Although Department of Buildings documents show that the funeral parlor occupied the two lower floors, it appears it subleased the second floor. In 1956, the Artists Equity Association headquarters listed 235 West 72nd Street as its address.

In 1991, the newly-organized Ortiz Funeral Home moved into the ground floor and is still there today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

235 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 235 West 72nd Street: