Countless Schools and a Countess

by Tom Miller

In 1898 A History of Real Estate, Building and Architecture in New York City noted that George C. Edgar’s Sons & Co. “has, to a great extent been instrumental in building up the West Side from 69th street to 95th street.” The article estimated the firm had built 175 private houses “of a substantial type,” and added “The best example of their work is No. 228 West 72d street, a house which has few peers, and none better in that section of the city.”

That 25-foot wide brownstone residence had been designed by Gilbert A. Schellenger, and completed a year earlier. Above its understated parlor level above the high brownstone stoop was a swelled bay, two floors tall. The underside was decorated with elaborate foliate carvings and it was crowned with a striking bronze railing. The recessed openings of the fourth floor were outlined by delicate picture frame-like molding and separated by paired free-standing Corinthian columns. A robust cast iron cornice a frieze completed the design.

Interestingly, it was not until April 1899 that a buyer was found for the upscale home. The New York Times wrote “It is reported that George C. Edgar’s Sons & Co. have sold to Justice Martin J. Koegh the residence 228 West Seventy-second Street.”

Koegh had been elected to the New York Supreme Court four years earlier. He and his wife, the former Katherine Temple Emmet, had a large family–four sons, four daughters and a stepson, Martin, Jr. In addition to his visible court rulings (he specialized in murder cases), Koegh was active in the Irish-American community. Katherine was the great-granddaughter of the Irish patriot Thomas Addis Emmet.

The family did not stay at 228 especially long. It was sold to Joseph G. Groff in 1904, who renovated it for use as his exclusive boy’s preparatory school, the Groff School.

An advertisement in the July 1904 issue of The Century Magazine announced “This school, though limiting absolutely its number of students, has outgrown its present quarters, and will move on August 1st into one of the largest and most handsome houses on the West Side, 228 West 72d Street, equipped with every modern convenience, including an electric elevator.”

Groff’s renovations included “board and rooms (with private shower-baths) unequaled,” and “modern bowling alleys, fencing hall, billiard room, etc.” It was, as the advertisement pointedly noted, “decidedly a school for gentlemen only.” (Groff retained sufficient living space in the house for his family, as well.)

The steep tuition millionaires paid to have their sons properly prepared for higher education earned Groff a fortune. On February 12, 1910 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that he had purchased “one of the finest estates on the Jersey coast, at Deal Beach…known as Kildysart.” The 50-acre estate was built for Standard Oil vice president Daniel O’Day, who had died. Groff paid over $1 million for the property–nearly 29 times that much in today’s money. The article explained “His intention is to conduct a summer and winter school at Kildysart, much along the same lines as the Groff School in Manhattan.”

Bolton disappeared, moving to Yonkers and assuming the identify of David Nally, a presumed bachelor. Unable to find Bolton’s whereabouts, Gertrude sued his father for $50,000 alleging the alienation of her husband’s affections. It never came to trial, but Gertrude was given $12 per week in support.

The activities offered at the Groff Country School–golf, horseback riding and such–were balanced at the Groff School by arrangements with nearby facilities. A September 1910 advertisement noted “Free use of one of the largest gymnasium in New York. Also swimming pool and athletic field–all conveniently near.”

Earlier that year Joseph C. Groff had had a serious scare. He and his seven-year old son, Jack, were on their way to Central Park in the family’s sleigh on January 16. The Sun reported “When they reached Columbus avenue Dennis Dehner…driving an automobile, came spinning down Columbus avenue. Dehner saw the sleigh too late. Even with the wheels locked by the brake the auto went crashing into the sleigh and crushed it.”

Groff was thrown ten feet from the accident while his son “tumbled in the snow unhurt.” Groff’s “right shoulder was hurt, but he is not thought to be seriously injured,” said the article. The horse, having been knocked to its knees and cut by parts of the smashed sleigh, was badly frightened. It headed south on Columbus Avenue dragging the remnants of the vehicle. The New York Herald said it “ran away, taking the sidewalk and causing a stampede of persons, who fled to doorways.” It was later caught by a policeman at 65th Street. After filing charges of reckless driving against the motorist, Groff, with a dislocated shoulder, took his son home.

In 1912 Joseph Groff relocated his school to 259 West 75th Street. The move may have added to his stress and at the end of September, according to the Glen Falls Daily Times, he was “suffering from a nervous breakdown.” Within just two weeks the 42-year old developed pneumonia. The complication proved too much, and he died on October 11.

228 West 72nd Street became a high-end boarding house run by Gertrude B. Winpenny. Hers was a fantastic story. Years earlier Gertrude had caught the eye of Bolton S. Winpenny, the eldest son of a wealthy Philadelphia family. Because his father was adamantly opposed to the romance on July 4, 1894 the couple eloped to Palmyra, New York. When the senior Mr. Winpenny found out, he disinherited Bolton–but he offered a carrot. If Bolton would leave Gertrude, he would receive $60 a week for as long as he stayed away from her. It was a tempting incentive, equal to about $1,850 a week today.

And so, Bolton disappeared, moving to Yonkers and assuming the identify of David Nally, a presumed bachelor. Unable to find Bolton’s whereabouts, Gertrude sued his father for $50,000 alleging the alienation of her husband’s affections. It never came to trial, but Gertrude was given $12 per week in support.

Now, in 1913, Gertrude decided to move on. Still unaware of her husband’s location, she informed her father-in-law that she would allow a divorce for the sum of $10,000 (more than a quarter of a million today). It put the long-hiding Bolton on a mission to discredit her.

On March 19, 1913 The Yonkers Herald reported “Mrs. Winpenny has been living in the fashionable West End avenue district of New York City, No. 228 West 72nd street.” The article told that Gertrude had recently taken in a new boarder, Mrs. Alice Johnson. She had no way of knowing that the woman was a private detective hired by her husband.

Using evidence provided by Johnson, Bolton Winpenny turned the tables on his wife, suing her for divorce and claiming she was having extramarital affairs with at least two men, Walter McClelland and John Stoddard. In court Alice Johnson testified “she had attended a theater with Mrs. Winpenny and a John Stoddard, that they went to supper afterward, and on the way home in a taxicab, Stoddard hugged and kissed Mrs. Winpenny, and the two smoked cigarettes together.” Even more shockingly, she told about “the visits of McClelland to the house and that he stayed sometimes all night, at other times staying until 2 o’clock in the morning.”

Gertrude Winpenny’s boarding house closed soon after the embarrassing trial and publicity. An announcement in the August 1914 issue of The Century informed readers of the “new residence” of the Coates School. “Mrs. Isabel D. Coates will receive in her home a limited number of girls who wish Art, Music, Languages, etc. Students may select their own Circular on application.”

By 1920 the personality of West 72nd Street was changing as mansions were either being converted to apartments and stores or demolished for modern structures. On June 8, 1920 the New York Herald reported that 228 West 72nd Street “will be altered into high class apartments.”

Now called the Teasdale Residence, the renovated house provided apartments for unmarried women and girl students. Women’s hotels and apartments had been popular for several decades, since females began entering the workforce with professions like shop girls, secretaries and garment workers. They provided a safe, affordable place to live.

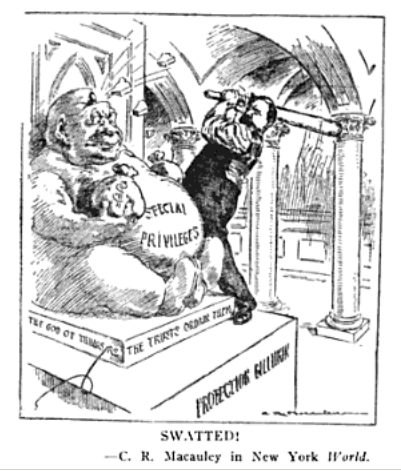

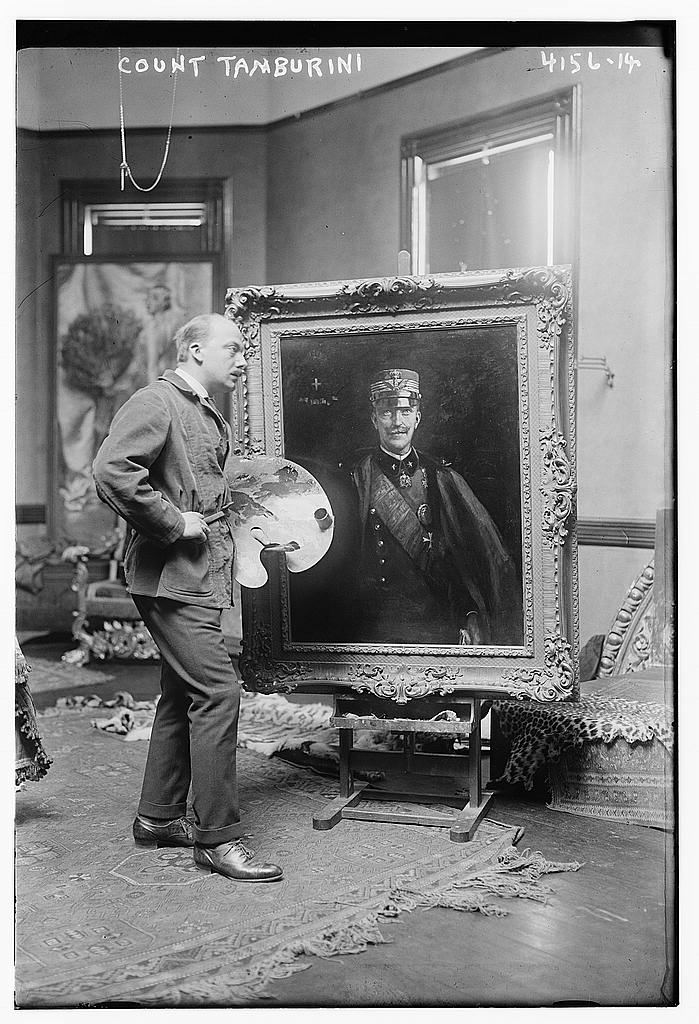

Within a few years the building accepted men as well. Charles R. Macauley, a former cartoonist with The World, and his wife had the fifth-floor apartment here in 1922. They took in a house guest, Countess Tamburini, when her husband, portrait artist Count Arnaldo Tamburini, left for Rome to do a portrait of Benito Mussolini at the end of the year.

At around 3:00 on the afternoon of January 30, 1923 the Countess received a telephone call. The caller said that a man had been taken to Roosevelt Hospital badly hurt and the card in his pocket had her name and number. She and Mrs. Macauley hurried to the hospital, only to find out they had been duped.

When they returned, they found the door to the apartment had been forced open and much of the Countess’s jewelry had been stolen. She estimated the value at around $105,000 in today’s money. The Daily News noted “The thieves had overlooked antiques valued at $22,000.”

When they returned, they found the door to the apartment had been forced open and much of the Countess’s jewelry had been stolen. She estimated the value at around $105,000 in today’s money.

Happily, all the loot was discovered by police in a Harlem pawn shop on February 3. Two days later the Daily News reported “Countess Tamburini, who is staying at the Macauley residence, was informed of the recovery yesterday and left her breakfast unfinished to cable the good news to her artist husband, now in Rome.”

In 1931 a school once again moved into the building. A notice in local newspapers read “Windsor P. Daggett announces a summer term of speech and acting at his Voice and Color Theater, 228 West Seventy-second street, opening July 6.”

The use of the word “theater” was perhaps misleading and by 1933 the facility was termed the Daggett School of the Spoken Word. That year it announced two new courses for the spring term: “Public Speaking for Professional and Business Men” and “Phonetics, Voice and Speech Control.”

By 1936 the former basement level had been converted to a bar and grill owned by former prize fighter Carey Phelan. He was at the Rockaway Beach Hotel on Labor Day that year when he became engaged in a conflict with professional golfer Bea Gottlieb. She charged him with rape and felonious assault in the ladies’ restroom, he countered that she had “marked him for the victim of her allure.”

According to Bea’s story, he followed her into the ladies’ room and attacked her. According to his, after he showed her where the restroom was, she said the lights were out. In court he said “I went in to find the light. She threw her arms around my neck. Then I turned on the light.” Phelan declared in court “that the whole case was a shake-down attempt” and that Bea had offered to drop the charges for $50,000.

On March 9, 1937 the jury acquitted Carey Phelan of all charges. Dejected, Bea Gottleib went home and swallowed a box of sleeping powder mixed with whiskey. When her attorney was unable to contact her, he called the police who found her unconscious at around 11:15 that night. Two days later doctors announced her condition had greatly improved.

A renovation completed in 1948 resulted in a restaurant and cabaret in the basement level and two apartments each in the upper stories.

The restaurant was home to Mrs. J’s Sacred Cow by 1970. The popular eatery was established in 1947 and was known for its steaks and lobster and entertainment. An advertisement in New York Magazine on April 25, 1988 noted it was “The place where the girls sing to you.” Mrs. J’s Sacred Cow remained in the space into the 1990’s.

Today unattractive storefronts front the lower two floors, but above the 1897 mansion is remarkably unchanged.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

228 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 228 West 72nd Street:

Meet Matt Gebhard and Lindsay Ronchi!