View of 226 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Tiller Dancing School

by Tom Miller

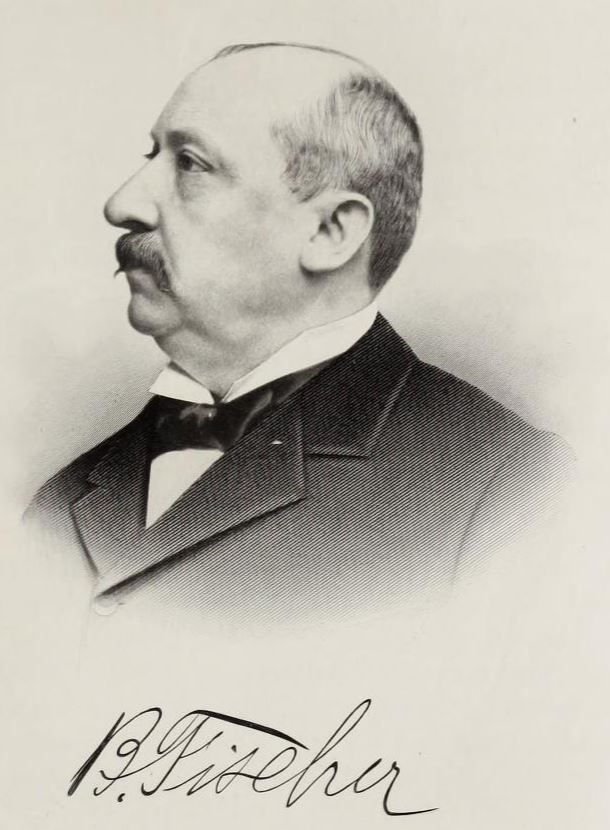

Born in Oberschopfheim, Germany in March 1840, Benedickt Fischer was a very wealthy and very busy man by 1896. He was the founder and head of the B. Fischer & Co., tea company, president of the American Encaustic Tiling Company, and vice-president of the silver firm, Mauser Manufacturing Company, (which later became Gorham Silver). He invested heavily in Manhattan real estate, as well.

In in April 1896 the esteemed architect Henry Fouchaux filed plans for a new residence for the Fischer family at 226 West 72nd Street, within one of the most exclusive residential districts in the city. Fouchaux projected the construction cost of the 23-foot-wide, four-story high-stoop house at $1.1 million in today’s money.

Construction took nearly two years to complete. The Fischer house exuded the wealth and refinement of its owners. The bowed two-story oriel at the second and third floors was crowned with a copper-railed balcony. The fourth-floor windows were recessed within a carved frame supported by Corinthian columns and an exuberant pressed metal cornice capped the design.

Benedickt Fischer and his wife, the former Katharina Ebling, had two children, William H., who was involved with B. Fischer & Co. and was a director in the Manhattan Fireproof Stabling Company, and a married daughter, Antonia Fischer Diefenthaler.

Upon his release, he showed his appreciation by hosting a “jollification concert and dansant” for the nurses of the Post Graduate Medical School and Hospital on May 1.

On the morning of Friday the 13th, 1903 Benedickt Fischer boarded the Ninth Avenue elevated train to head to his office on Greenwich Street. Along the way he suffered a heart attack and was taken to the Hudson Street Hospital. He died there two days later at the age of 63. William, a life-long bachelor, remained in the 72nd Street house with his mother.

In 1915 William was hospitalized with a relatively long-term illness. Upon his release, he showed his appreciation by hosting a “jollification concert and dansant” for the nurses of the Post Graduate Medical School and Hospital on May 1. The concert portion of the event was followed by “dancing of ancient and modern steps by all the guests and a buffet supper,” reported the New York Herald.

Two years later, on July 28, 1917, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that the Arion Society had leased 226 West 72nd Street for a period of three years. “Practically no structural alterations will be made by the club, which will take possession at once,” said the article. Given the Fischer family’s roots, it is not especially surprising that they leased their former home to a German-American musical society.

With World War I raging in Europe, American sentiments towards Germans and German-Americans was bitter. The Arion Society displayed its American patriotism on New Year’s Eve 1917 by hosting a dinner for 25 soldiers. The Brooklyn Citizen reported, “The dinner will consist of all things that suggest home and every effort of the club members will be made to see that the soldier boys will spend the last Sunday of the old year in having a good time.”

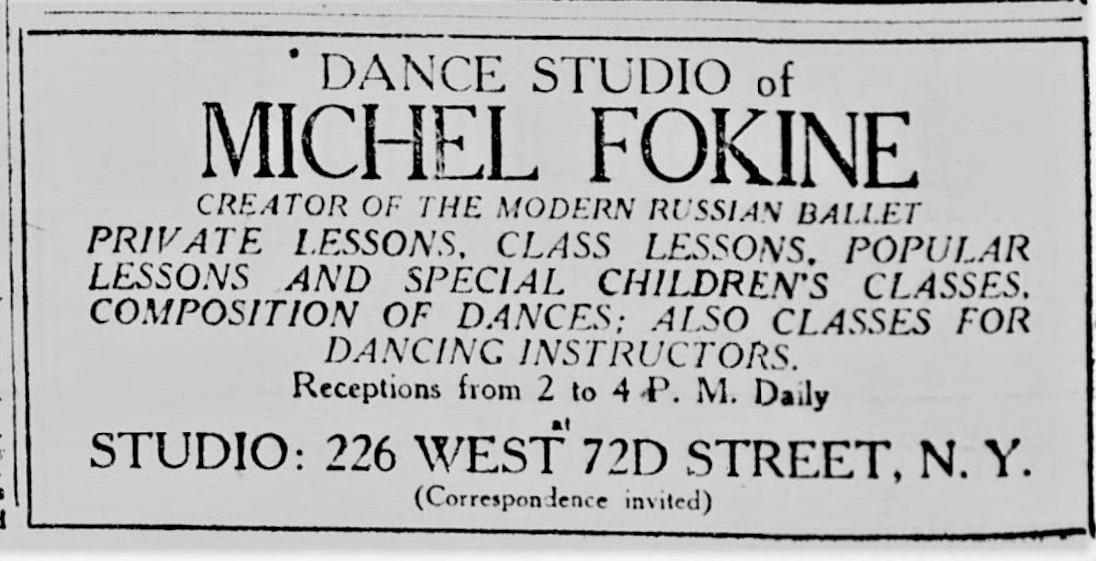

In 1920, with the Arion Society’s lease having expired and the 72nd Street block no longer one of high-end private homes, William Fischer’s next leasee operated the house as a high-end rooming house. Michel Fokine moved his dance studio into the basement level.

Among the more colorful of the tenants was Manfred P. Welcher, field secretary of the Anti-Cigarette League of America, who took the parlor floor for just one month in November 1921. Upon arriving, he warned New Yorkers, “The cigarette evil is more widespread than ever before and more tobacco is being made into cigarettes.” The Standard Union explained he planned to deliver “another set of lectures against juvenile tobacco using at local schools.” His secret weapon was girls. He told a reporter:

I always assume that girls do not smoke. Therefore, I merely urge them to work with me against smokers and smoking. I ask them to try to stop the boys smoking. I go further: I ask them to ignore boys who smoke and resolve to have nothing to do now or hereafter with smokers.

Lois Josephine Cross moved in in 1920 after separating from her husband, vaudeville comedian Duke Wellington Cross a few months earlier. On January 12, 1923, she testified in her divorce hearing, lamenting to the judge that the number 13 was her “hoodoo number.” She explained that Cross had deserted her after 13 years of happy married life on July 13, 1919 and that he filed for divorce 13 months later. The Daily News said, “No alimony was asked by Mrs. Cross, who is wealthy.”

On January 12, 1923, she testified in her divorce hearing, lamenting to the judge that the number 13 was her “hoodoo number.”

The basement space which had been Michel Fokine’s dance studio was taken over by English-born musical theater director John Thomas Tiller. Here he had offices and a “training studio” for theatrical dancers. At one point Florence Ziegfeld took 48 of his girls under contract for his Ziegfeld Follies. Other producers to hire Tiller girls were Charles Frohman, George White, Augustin Daly and Charles B. Dillingham.

Tiller put a head Tiller Girl from England, Mary Read, in charge of the Tiller School so he could spend most of his time in England. On August 10, 1925, John Tiller made his annual visit to the New York school. He became ill and died in Lenox Hill Hospital on October 22 at the age of 70. Mary Read continued to run the school.

In 1927, the Benedickt Fischer estate sold 226 West 72nd Street to Henry J. Lange. Architect Samuel A. Hertz was hired to renovate the former mansion. He removed the stoop and added a two-story commercial extension at the property line. The top three floors, the exteriors of which went untouched, were converted to non-housekeeping apartments (meaning there were no kitchens).

The Tiller Dancing School remained in the lower space at least through 1933. In the early 1950’s the Crystal Dairy Supermarket occupied the ground floor. Another renovation completed in 1955 resulted in a store at sidewalk level, and a total of nine apartments on the upper floors.

In 1988 Essen West opened in the commercial space. The kosher specialty shop was one of several in the neighborhood—a situation that was mutually beneficial. Six years later, in September 1994, one of the owners, David Gross, told a New York Times reporter, “It’s tough up here, but we’ve made it a hub here by staying on with the others.” Nevertheless, it eventually closed and today the ground floor is home to a nail salon, recently shuttered.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

226 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 226 West 72nd Street: