View of 216 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

A Winning Gambler’s Bad Luck

by Tom Miller

In October 1886, architect C. P. H. Gilbert, well-known for designing mansions, filed plans for three side-by-side brick-and-stone houses at 216 through 220 West 72nd Street for developer William H. McCormack. Each of the four-story residences would cost $24,000 to construct—more than $680,000 today. Completed in 1888, the eastern-most house, 216 West 72nd Street featured a three-story angled bay crowned by a solid-walled balcony. It served the sleeping porch tucked deeply within a maw-like arch at the fourth floor (most likely used by servants during the insufferable summer months).

The original owner, James Moses, remained in house for ten years. When it was offered for sale in November 1898, the Real Estate Record & Guide noted, “As this is one of the choicest pieces of property on the West Side, the entire real estate fraternity will look for the results of this offering with interest.” The house next door had recently been purchased for the equivalent of more than $2.5 million today.

Thomas and Jennie Reid were the purchasers. Despite their wealth, they rarely appeared in society columns. That changed on September 20, 1900, when the house was the scene of a well-publicized wedding. The Brooklyn Standard Union reported, “David Saville Muzzey, the well-known writer on religious and ethical topics and a teacher in Dr. Felix Adler’s school, and Miss Ina Jeanette Bullis, an artist, were married yesterday afternoon at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Reid, 216 West Seventy-second street, Manhattan.” The Reids’ two sons, Egbert and Stuart, acted as ushers.

In 1902, the Reids sold the residence to a most fascinating character, John E. McDonald, and his wife, Augusta. Born to Irish immigrants in 1871, McDonald had started his career as a bartender in his father’s saloon at 119th Street and Third Avenue. In 1878 he went to Saratoga, New York to work in a billiard parlor, and then as a special policeman in the grandstand of the Saratoga racetrack.

McDonald began betting on the horses and had an incredible, innate ability to pick the winners.

McDonald began betting on the horses and had an incredible, innate ability to pick the winners. The Washington Times later said, “His first winning of particular consequence was in a selling race on a horse called Skylark…McDonald made between $10,000 and $15,000 on this coup and, this giving him confidence, he struck out boldly for himself.

By now McDonald was a millionaire and owned a stable of 14 horses. Nevertheless, he still had much of the demeanor of a streetwise Irish immigrant. A friend said, “He had a direct manner of speaking that seemed to hit the nail on the head every time. He spared no one whom he did not like, and when he didn’t like a man he was against him horse, foot, and dragoon.” Yet the ill-educated McDonald tried hard to improve himself. The Washington Times said, “he became very ambitious to improve his general knowledge and read a great deal…He was the possessor of a valuable and extensive library.”

Although still known in horse racing circles, he was now focused on communications. He was president of the Boston and New York Telephone and Telegraph Company, president of the Knickerbocker Telephone and Telegraph Company, and treasurer of the Massachusetts Telephone and Telegraph Company, and the Telephone, Telegraph, and Cable Company of America.

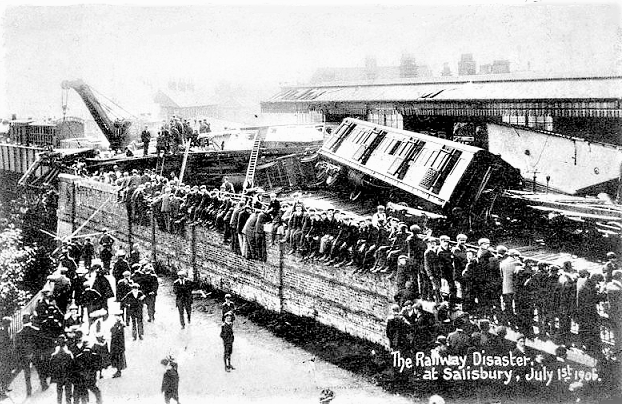

The couple was scheduled to sail to England in mid-June 1906, but John was detained. Augusta went on and her husband sailed two weeks later. His ship docked at Plymouth, England, on July 1. New York Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr. had been on the same ship. Just before the London & South Western Railway boat train departed for London, McClellan gave McDonald his reserved berth ticket and stayed behind. The simple act of generosity saved one man’s life and ended the other’s.

The train was filled mostly with wealthy Americans. A rumor later held that some of them had bribed the engineer to run the train as fast as possible. The express train sped past the Salisbury Station at an estimated 70 miles per hour—40 miles per hour faster than the permitted speed at the very sharp curve. The luxury train derailed, killing 28 passengers, including James E. McDonald.

McDonald’s body was brought back to New York City and his funeral held in the drawing room of 216 West 72nd Street on July 26, 1906. In reporting on it, The Binghamton Press noted, “His wife, who was formerly Miss Augusta Bingham of this city, is slowly improving.”

Because McDonald had died with no will, Augusta was entitled only to a “dower right” to the estate—or one-third its value. The other two-thirds was divided among his brother and three sisters. Among her share, McDonald’s sister Agnes Raywood received the 72nd Street house.

Coincidentally, Agnes’s husband, Thomas H. Raywood, was a real estate operator. He first leased the house to stockbroker Lemuel Coleman Benedict. A descendant of Thomas Benedict who arrived in New Amsterdam in 1662, he was the head of the brokerage firm Benedict, Drysdale & Co. He married Carrie Bridewell on June 4, 1908, just after leasing 216 West 72nd Street.

Interestingly, when Raywood leased the house to the Brown School of Tutoring in 1912, the Benedicts remained in the upper floors. It was next home to the Berkeley School, which signed a lease in 1914. The accommodations enjoyed by Lemuel and Carrie Benedict got tighter. Sharing the upper floors with them now were Maurice S. H. Unger, the school’s headmaster, and Professor Frank Sergeant Hoffman, his wife and daughter, Grace May.

The Berkeley School moved on in 1916 and Thomas H. Raywood leased 216 West 72nd Street now to Robert Hosea, “as a conservatory for music.” Nevertheless, the Hoffmans and the Benedicts remained.

Interestingly, when Raywood leased the house to the Brown School of Tutoring in 1912, the Benedicts remained in the upper floors.

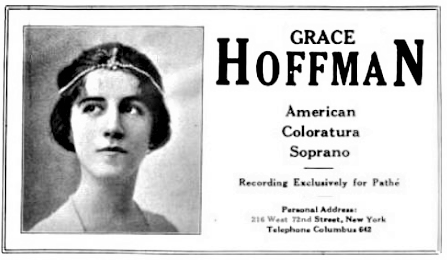

When Grace Hoffman married Dr. Jesse Willis Amey in 1918, the newlyweds remained in the house. Grace, a coloratura soprano, continued to use her maiden name professionally. She presumably took a break from her schedule of recitals in 1919. On March 16 that year a son, Jesse William Amey, Jr. was born.

The three families remained in the residence into the 1920’s. The musical conservatory in the lower section was replaced by the Comins Circulating Library in 1923, which became the Cresser Circulating Library the following year.

By then West 72nd Street had severely changed, as shops and apartment buildings replaced the former mansions. In 1927, 216 West 72nd Street was significantly altered. The stoop was removed, and the ground floor became a store, the second floor held an office and one apartment, and the upper floors became non-housekeeping (meaning they had no kitchens) apartments.

The commercial space became home to the Sunshine Shoppe where, according to The Vaudeville News, “You can get silk hose and bags and toilet articles and knick-knacks at as low a price as anywhere in the city.”

The store space would see a wide variety of tenants over the next few decades. In 1934 the brokerage firm of Granberry & Co. opened an uptown office here, and by 1941 the Daniel Reeves food market occupied the space. That was replaced by the Shop-O-Rama Store by the end of the 1950’s where consumers could get anything from a “pulley bubble lamp” to a “tater baker” to a portable stereo phonograph that looked like an overnight suitcase when closed.

From 1964 to around 1984 the Broadway Television Center occupied the store space. It was replaced by Uncle Steve, which sold audio-video equipment like camcorders, televisions and VCRs and cassette decks. Since 1992 the shop has been home to the Joseph Pharmacy.

Although the façade has been painted a monochromatic off-white, little imagination is necessary to recognize the once-proud home of West Side millionaires above the storefront.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

216 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 216 West 72nd Street:

Meet Sharif Shoukry