Lost Colonial Times

by Tom Miller

On July 2, 1890 The New York Times ran a two-line notice saying “Permission has been granted by the Supreme Court to the Occident Club to change its name. It will be known as the Colonial Club of New-York.” The change was perhaps surprising to readers since the club had been formed only a year earlier, in April 1889.

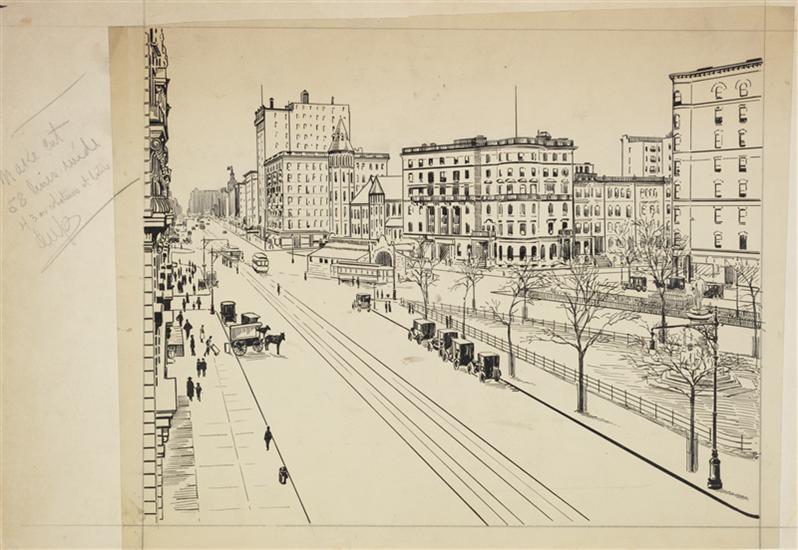

As the Upper West Side rapidly developed, wealthy businessmen moved their families into its expansive mansions and elegant rowhouses. But there was a problem—the area was inconveniently far from Manhattan’s exclusive men’s clubs. The clubs were not merely a sign of prestige; they were a near-necessity. In the summer months, for instance, when families packed up for Newport and other resorts, the heads of the household stayed back during the week to conduct business. With their mansions closed for the season, it was their lavish clubs that offered the tycoons meals and, often, sleeping arrangements.

To fill the void, moneyed Upper West Side gentlemen formed the Occidental Club—so named because its members all hailed from the West Side. Further consideration brought about the change. The New York Times explained that the new name reflected the district which “abounds with relics and associations of colonial times, and [the club] has the nucleus of a very valuable collection of articles associated with the colonial period.”

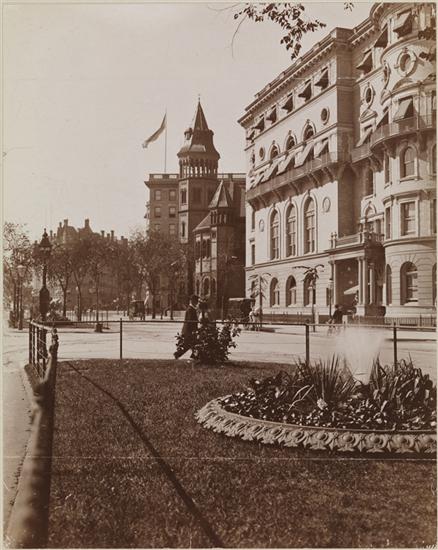

By the end of summer a peculiarly-shaped lot had been acquired at the southwest corner of the Boulevard (later renamed Broadway) and 72nd Street and on October 17, 1890 architect Henry Franklin Kilburn filed plans for the new clubhouse. Busy at work on the Upper West Side, Kilburn’s West-Park Presbyterian Church had just been completed at Amsterdam Avenue and 86th Street, and his West End Presbyterian Church further north on Amsterdam at 105th Street was under construction.

By now membership in the club had risen to about 300 and “includes professional men who live on the west side of the city between Fifty-ninth and, say Ninety-third Streets,” approximated The New York Times. The day following the filing of plans, the newspaper noted that “The style adopted by the architect was that of the colonial period” and said “The clubhouse will stand within sight of the porch from which Washington watched the retreat of his army from Long Island and within sight of the walls within which Alexander Hamilton died.”

Despite its substantial distance from the established club district, the new Colonial Club would hold its own. The land had cost the club $85,000 and projected costs for construction were $175,000. Officers predicted that the finished structure, with furnishings, would cost $275,000—about $7 million today.

A few weeks later, on November 2, The Times remarked on an innovative concept in the design of the clubhouse—space allotted for women. “The Colonial Club is the latest club to adopt the plan of granting the freedom of a portion of its clubhouse to the wives and daughters of its members. There will be a private entrance for ladies in its clubhouse, now in course of erection…on the third floor of the house will be a suite of apartments for their use, consisting of dining room, reception room, boudoir, etc.”

As word of the club’s intended lavish appointments spread, there was a rush to join. By the end of November the membership had soared to 400.

The cornerstone was laid on April 4, 1891 “with fitting ceremonies,” according to The Times. Within the copper box laid in the cornerstone were club manuals and documents, a photograph of General Sherman’s funeral passing Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street, a Civil War badge of the Grand Army of the Republic, copies of various newspapers and poems written by member William M. Kerr to “Our Children’s Children’s Children.”

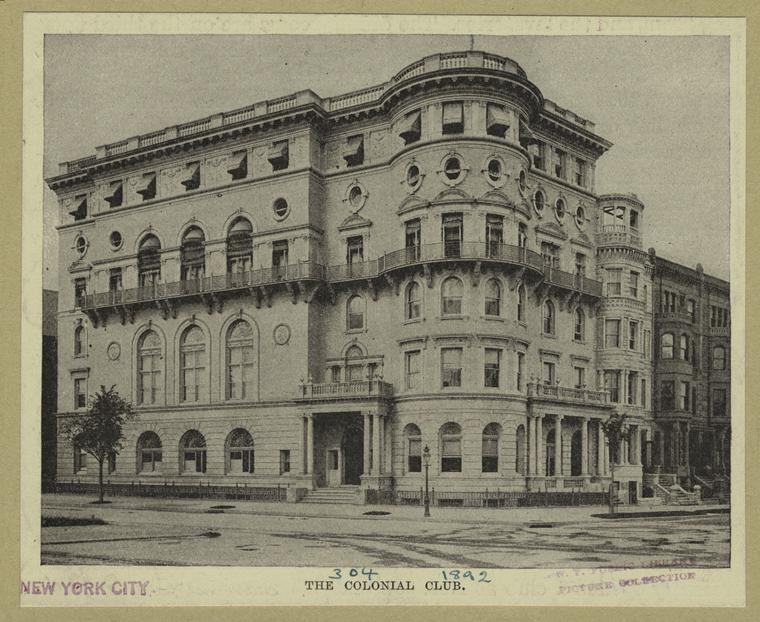

By now, the estimated cost had risen to $320,000. The Times now described the architecture of the rising structure in greater detail, saying it “will follow the colonial style. The material will be gray limestone up to the second floor; above that long, thin gray brick, with white terra cotta trimmings, except the top story, which will be entirely of terra cotta and finished with a rich balustrade of the same material.” Above it all would be a summer garden and observatory.

The roof garden was paved in brick and ornamented with potted plants in the warm months. Reporters were told it would be “used as a promenade and Summer garden.”

“All the arrangements of the house are the very latest pattern, and in point of completeness challenge, if not excel, those of any other New-York club,” insisted The Times.

Although wealthy families abandoned the stifling city in the summer months, the husbands left behind during the workweek suffered. The idea of a roof garden was especially inviting. At the height of the summer that year The New York Times remarked “Those who have experienced the delights of one of these roof gardens on a torrid Summer night, when their luckless fellow-mortals were sweltering in the streets below, may be counted on as uncompromising advocates of the innovation. Little expense is involved in fitting up a roof garden, and while there are no end of arguments in favor of the idea there is absolutely no good reason against it.”

Construction on the great clubhouse continued into the following year. In February 1892 the opening was planned for “some time in April.” A newspaper reported that all the club’s energies were being focused on arranging for a “monster reception.” April came and went and the grand opening was pushed off until the fall. Officers felt that the clubhouse should be fully furnished and, since most members were away during summer months, postponing the opening was reasonable.

Nevertheless, the Colonial Club moved into the new building on April 16 with little fanfare. Guests were amazed at some of the innovations. There was an in-house “opera house,” and a ladies’ gallery above the dining room where women could look down on the male members.

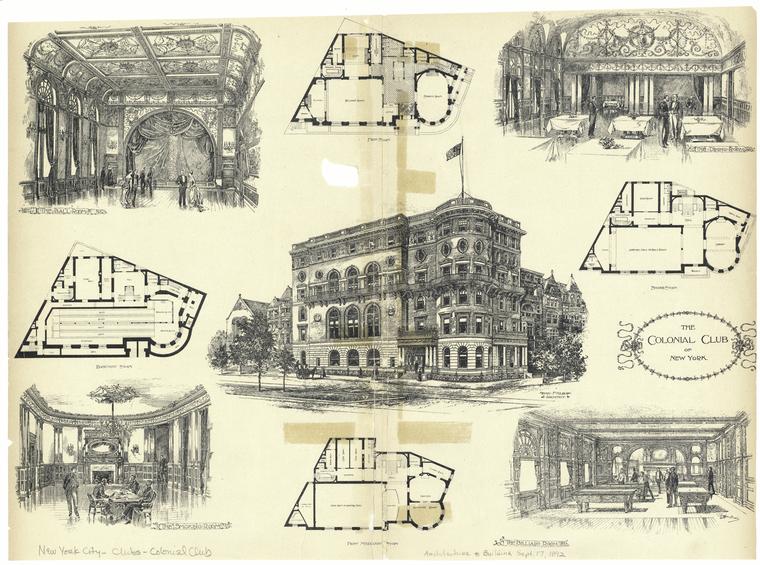

In the basement were four bowling alleys and the ventilation, heating and other engineering rooms. The ground floor housed the billiard and smoking rooms along with the dramatic Colonial-inspired staircase. In the great entrance hall was a large fireplace with oak window seats on either side. A glass-doored café allowed members to watch the billiard games.

The New York Times described the ladies’ accommodations in detail. “Just behind [the oval smoking room] is the private entrance for ladies, on Seventy-second Street, and a private hallway, so arranged that the fair visitor may step directly into the elevator and gain access to the ladies’ parlor and dining rooms on the floors above unobserved by members of the club; or, if she so desires, the guest of the club can go down stairs by a private staircase at the bowling alleys, which will be reserved for the ladies of members’ families at certain hours of the day.”

On the second floor was the enormous ballroom—66 feet long and 32 feet wide with 25-foot high ceilings. Also on this floor were the library and a writing room, along with other assorted rooms. The main dining room on the third floor opened onto a beautiful iron balcony that wrapped the building. The private dining rooms were designed so they could be opened and the entire floor prompt service is insured and the certainty of hot dishes being served hot is guaranteed.”

On the top floors were ten suites of apartments for members, each of which included a parlor, bedroom and bathroom. Servants bedrooms were included on the side of the top floor along with the laundry and, pastry kitchen.

The roof garden was paved in brick and ornamented with potted plants in the warm months. Reporters were told it would be “used as a promenade and Summer garden.”

“All the arrangements of the house are the very latest pattern, and in point of completeness challenge, if not excel, those of any other New-York club,” insisted The Times.

The New-York Tribune added “It stands between two tall apartment-houses, and its architecture is clean-cut and strong. The entrance is at the right, under a portico with tall pillars, and the general effect is one of quality picturesqueness.”

The Colonial Club was unique among the other clubs of the city in that it drew its membership nearly exclusively from Upper West Side residents. “There are not, perhaps, as many millionaires on its membership roll as are to be found in some of the other purely social clubs,” noted The Times, “but all of its members are well to do, and the average wealthy of its members would probably compare very favorably with the average of any except the wealthiest clubs.”

Now that the Colonial Club was ensconced in its new clubhouse, some changes needed to be addressed. The membership had risen to 600 and with the completion of the beautiful building applications flowed in. Several new amendments were made to the constitution: the membership limit was raised to 800; and two classes of membership were initiated—non-resident and life members. Now members living outside a 50-mile radius of City Hall would pay only $25 dues each year, instead of the $50 resident members paid.

Prior to the grand opening, the ballroom was rented for an elaborate banquet and ball to celebrate Mexican Independence Day. Over 100 Mexican-born businessmen and their wives headed for the new facility on the night of September 15, 1892. The event was to be presided over by Dr. Juan N. Navarro, Mexican Consul to the United States. But something happened.

“Threescore or more gentlemen, who are proud to own Mexico as their native land, went to the Colonial Club at the appointed hour. A few were accompanied by their wives. They were informed by the Superintendent of the clubhouse, according to Consul Navarro, that the rules of the club forbade the presence of ladies. There could be no exception made in this instance, and although the banquet had been prepared the entire company of Mexicans withdrew rather than forego the pleasure of the ladies’ company,” reported The New York Times the following morning.

The group went to the residence of Consul Navarro where “they enjoyed themselves in a social way. There was no banquet and there were no speeches, but there was plenty of music and good cheer.”

If the Mexicans felt slighted, they no doubt felt more so when the Colonial Club celebrated its grand opening the next month—with many women in attendance.

“Flowers there were in abundance, and fine pictures, and glittering refreshment tables that appealed to the aesthetic tastes as well as to the appetite,” reported The Times on November 16, 1892. “And in the exquisitely-decorated rooms were scores of charming gowns of varied hues, displayed by fair women whom Mr. [Chauncey] Depew described as combining the dignity of the colonial past with the bright freshness of the present.”

Two orchestras played throughout the evening and club President Edward W. Scott told the group “We wish to make the Colonial the best stopping place, the safest harbor, the most enjoyable home on the west side, and I hope that in hospitality and comfort it may be surpassed nowhere. We wish our people to feel welcome at all times.”

Railway tycoon Chauncey M. Depew spoke favorably about the Upper West Side. He said, according to The Times, that “His observation had convinced him that the west side was populated by young men and pretty girls. There were very few bald heads on the west side. The Colonial Club was a shining example of the development and growth of the west side.”

Depew made specific reference to the forward-thinking idea of allowing women in the building. “Formerly the ladies regarded the club as an enemy of the domestic circle. Now the club opens its doors to the ladies and she thinks it is a good thing. Whenever a woman can go where her husband goes she is satisfied. The club should never be permitted to interfere with the family, for the family is the foundation of the community.”

Among the Upper West Side entrepreneurs who were counted among the now 700 members were the Macy’s Department Store executives—the Websters and the Strauses. On December 2, 1892 they were all in attendance at an “Egyptian Dinner” in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Webster who were about to depart on a voyage to Egypt. The dinner was hosted by George Kissam and among the diners at the exotic event were Mr. and Mrs. Isidore Straus (who would famously go down on the H.M.S. Titanic), Nathan Straus and other important West Side businessmen.

The success of the Colonial Club was reflected in the many elegant and festive dinners and balls held here in the first years. ON January 29, 1892 The Times reported “the beautiful white-and-gold banquet hall in the Colonial Club…was the scene of a brilliant social assembly last night. The occasion was the first of a series of club dinners which is destined to add much to the gayety of that prosperous and progressive organization. There were flowers in plenty and music without stint, and the well-supplied tables gleamed with myriads of bright-colored lights.”

Not everyone at the dinner was from the West Side. Included in the 230 persons were the influential Bishop Potter, Henry Villard, William Rockefeller, and former Connecticut Governor Lounsbury. Bishop Potter spoke in “unstinted praise” of the architect, Henry Kilburn, and brought up again, the concept of women being allowed in.

“The organization was not a club only—it was, in a certain degree, a family for one of the elevating purposes of the club was to enjoy the society of pure and honorable women.”

It would not be long, however before internal strife reared its head at the Colonial Club. As with most social clubs, the membership became divided between the older, more conservative men and the younger, less straitlaced members. As election time for officers drew near, the old guard threw a dinner to form a nomination committee and did not invite any of the younger group. Trouble ensued.

On May 8, 1894 The Sun reported that “The Roses and the Thorns had a red-hot battle at the Colonial Club last night. The Colonial Club is a leader among the upper west-side clubs, and has a handsome house at Seventy-second street and the Boulevard. It has never had a fight before, and there has never even been any dissention among the members. The present row, as near as it can be learned, came over a dinner party at the Manhattan Club.”

The newspaper called the young blood “the Roses” and the “old members, the hard shells, or Thorns.” The older members had already made their nominations and the voting began before the young “Roses” crashed the dinner. It was too late and the old guard’s choices were elected.

Railway tycoon Chauncey M Depew made specific reference to the forward-thinking idea of allowing women in the building. “Formerly the ladies regarded the club as an enemy of the domestic circle. Now the club opens its doors to the ladies and she thinks it is a good thing. Whenever a woman can go where her husband goes she is satisfied. The club should never be permitted to interfere with the family, for the family is the foundation of the community.”

“One of the leaders of the Thorns was approached later. He said: ‘oh, the sweet young things. Their papas will have to spank them to-night. Sad, isn’t it?’”

The older members got their way; but there would be bad feelings among members for years.

The following year on March 27, 1895, the Colonial Club initiated the first of what would be a highly anticipated annual event—an art exhibition of paintings, sketches and sculptures loaned by members. That first show included 65 paintings, including several, which had won prizes. There was a George Inness landscape “The Pasture,” Frederick Church’s “Wood Nymph,” and works by Rousseau, Dupre, Diaz and Corot.

Most New Yorkers were surprised when, just a decade after the club opened its doors, the Equitable Life Assurance Society of New York began foreclosure proceedings against the Colonial Club on July 13, 1903. Although club members said the financial difficulties started when the initiation fees were abolished, The New York Times had its own opinion.

“It is not on Fifth Avenue, where nearly all the social clubs of any importance are situated, nor is it even in that vicinity of the center of town. It is in a purely residential district. It does not offer the inducements for social preferment which is one of the objects of a club on its lines. It was intended to be the gathering place of the wealthy element building on the west side. It is too far up town for luncheon, and in fact, is altogether out of the way.”

The magnificent clubhouse was scheduled to be auctioned on November 4, 1903. Hope was that a wealthy member would purchase the building and save the club. In fact, that is exactly what happened—almost.

Robert E. Dowling placed the successful bid of $210,000. “Mr. Dowling is a member of the Colonial Club,” said a newspaper, “and after the sale said that while he made the purchase solely in an individual capacity, it is very probable that a lease will be arranged so that the club can continue in undisturbed possession of the property.”

Within a month Dowling sold the property to the Seventy-second Street Realty Company. The Colonial Club reorganized on December 4 with the same name and signed a lease on its clubhouse. The president of the old Colonial Club stated “The new organization will continue in a better and more effective way the purposes of the old.”

But the Club’s good intentions failed. Only a month later the Club reorganized again. On January 8 1904 the Commonwealth Club was formed with 300 “well known business men living on the West Side,” according to the New-York Tribune. That membership was a significant drop from the over 1,000 on the rolls of the Colonial Club just before its financial collapse.

The Tribune said “The club has leased the old Colonial Club building, Seventy-second-st. and Broadway. This is the final outcome of the failure of the Colonial Club, which formerly owned the clubhouse.

“The Colonial Club for many years ranked as one of the best social clubs in the city. Its membership comprised many men of high social distinction. Owing to bad management, however, in recent years, debts accumulated…The clubhouse is one of the most attractive architectural structures in the upper West Side of the city.”

But the days of sumptuous club living in the handsome building were numbered. The Commonwealth Club did not last a year. There was a glimmer of hope in October 1905 when the newly-formed Constitution Club began looking for a home. The club included on its rolls then-President Theodore Roosevelt, former President Grover Cleveland and Mayor George B. McClellan.

The Sun reported on October 18 “They are thinking of leasing the old Colonial Club…for a temporary home.” It was not to be.

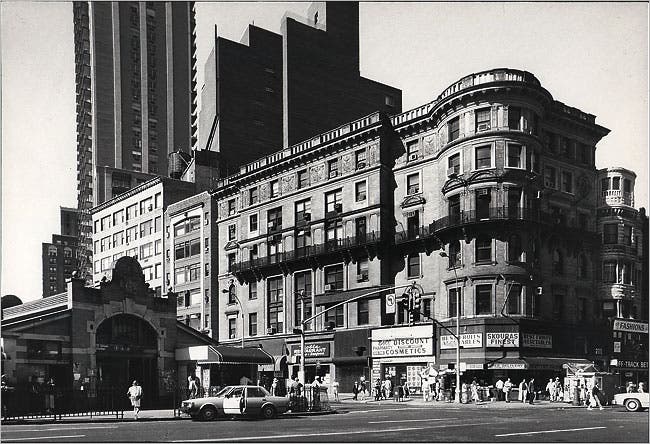

The once-grand clubhouse with its opera house-ballroom, sumptuous dining room and grand staircase was eventually gutted into retail spaces and offices. The neighborhood suffered a severe decline in the second half of the 20th century. A small green space directly across from the old Colonial Club, gained the infamous nickname “Needle Park” for its drug dealers, addicts and homeless people who gathered there.

In 2006, the former exclusive club building was barely recognizable; encrusted with advertisements and shop signs. As developers eyed the valuable corner property, preservationists implored the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the structure a landmark—three times. Each time the Commission refused the applications.

In the fall of 2007, it was covered with black construction netting as demolition workers prepared to raze it. By the middle of November the old building that the Real Estate Record and Guide had called a “Colonial Palazzo” was gone.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

200 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 200 West 72nd Street: