View of 175 West 72nd Street from southwest. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Van Dyke

by Tom Miller

Both Harry Mulliken and Edgar Moeller graduated from Columbia University’s School of Architecture in 1895. Mulliken opened his own practice around the turn of the last century and in 1902 he and Moeller went into partnership as Mulliken & Moeller. The two specialized in apartment hotels like the Bretton Hall Hotel, the Hotel York, and the violet-colored Lucerne Hotel.

On July 29, 1905 the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that Mulliken & Moeller, “are making revised plans for the 12-story 34-family apartment house” on the northeast corner of 72nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue for developers Ripley Realty Co. The Van Dyke, as it would be known, would have a near twin, the Severn, on the southeast corner of 73rd Street and Amsterdam, separated by a service alley.

The specification of “apartment house” was significant. The “hotel features,” like maid service, had been omitted and kitchens—so obviously absent in apartment hotels—were included. Both buildings were completed in 1906. The Record & Guide advised, “The Van Dyck has three apartments on each upper floor of eight to eleven rooms, with two and three baths.” There were two sets of elevators—one for residents and another for servants and “provision men.” The article said, “the tenants have most of the conveniences of a private house, without some of its disadvantages.” Included in those conveniences were a “completely equipped laundry” and “concealed service elevators.”

Occupants who could afford the equivalent of $8,000 per month rent today for a 9-room apartment were quite often mentioned in society columns. On December 1, 1911, for instance, The New York Times announced that “Mrs. And Mrs. Edward J. Rickert, of 175 West Seventy-second Street, gave a dance last night at the Plaza to introduce their daughter, Miss Helen Rickert.”

Whispers among society hinted that she was having an affair with yeast mogul and former Cincinnati mayor, Julius Fleischmann.

Among the long-term tenants were the Foster family, here by 1914. Scott Foster was the president of People’s Bank. He came to New York City from his hometown of Newburgh, New York in 1853 and in 1859 formed the dry goods firm of Foster Brothers. He left that thriving business when he became president of the bank.

Living in the apartment were his two of his three adult sons—John Hegeman, Eugene Gray—and a daughter, Jennie. Foster was a member of the exclusive Union League Club, and elder in the Rutgers Presbyterian church and a member of the council of New York University.

In 1919, Laura G. Heminway divorced her husband Lewis and moved into the Van Dyck. The couple had two young children, Louis and John, eight and five years old respectively. Whispers among society hinted that she was having an affair with yeast mogul and former Cincinnati mayor, Julius Fleischmann. The married 47-year-old had much to offer. He was, as well, the president of the Union Grain and Hay Company, the Market National Bank, the Security Savings Bank and Safe Deposit Company, and the American Diamalt Company.

Rumors turned to fact on January 21, 1920. That day, Fleishmann’s wife, Lilly, divorced him and two days later The New York Sun reported that he and Laura Heminway would be married that afternoon. “That his marriage to Mrs. Heminway had been arranged for to-day will come as a surprise to their friends in both New York and Cincinnati.” Laura commented to reporters, “There is no extraordinary romance about our engagement. What romance there is began about a year ago.”

RThe wedding took place in Laura’s apartment after a clergyman willing to perform it was finally found. Two other preachers had refused “based on the ground that both Mrs. Heminway and Mr. Flesichmann were divorcees,” said the New-York Tribune. The newspaper noted, “Mr. Fleischmann is forty-eight years old. His bride gave her age as twenty-six.”

Scott Foster and his daughter were still living in the Van Dyck at the time of the well-publicized nuptials. Never married, Jennie had graduated from Smith College in 1897 and had devoted her time and money to philanthropic causes. She was a director of the women’s branch of the New York City Missions and manager of the women’s branch of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church.

On January 26, 1922, Foster suffered a fatal heart attack in the apartment at the age of 85. Eleven months later Jennie died there at the age of 42 following a brief illness.

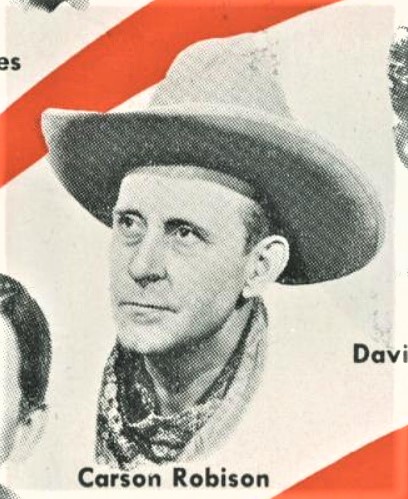

Living here during the World War II years was songwriter and singer Carson Robison. Harriet Van Horne, a World-Telegram columnist, reported in 1943 that one of conductor Arturo Toscanini’s favorite records was a hillbilly tune titled Mussolini’s Letter to Hitler, with Hitler’s reply on the flip side. Although it was “decidedly on the corny side,” a staff member at Toscinini’s Riverdale house said, “the Maestro roars every time he plays it, thumping his heel like an old-time fiddle player.”

Two other preachers had refused “based on the ground that both Mrs. Heminway and Mr. Flesichmann were divorcees,” said the New-York Tribune.

Upon reading that account, a reporter from the PM Daily searched out the composer. “Carson Robison, who is 52, lives at 175 West 72d St., and has composed some 300 cowboy tunes, including Carry Me Back to the Lone Prairie,” said his article.

Robison played the record for his visitor, who printed a few of the lyrics, including parts of Hitler’s Reply to Mussolini:

The lack of parades must hurt you,

For I know how you love to strut.

And I’m sorry your wardrobe is shabby

But we’ve all had to take a big cut.

However, I’m sending some leather

And with it I give you this toast:

Reinforce the seat of your britches,

That’s where you’ll need it the most.

For decades, the commercial space on 72nd Street had been home to the real estate firm of Joseph H. Nassoit. He opened his business in 1905 and in 1953 consolidated with another firm to form Nassoit-Sulzberger & Co. In 1960, its offices moved to Madison Avenue.

The space became home to Fliks Videos, owned by Farid Galani. The store stocked an inventory of over 25,000 movies which could be rented for two-day periods. Galani offered a tantalizing amenity over other film rental stores: “fast free delivery to your door in a guaranteed 58 minutes or less.” Unfortunately, Galani found a way to cut down overhead. On September 16, 2008, The New York Times reported he had been charged “with trademark counterfeiting in the second degree…and failure to disclose the original of a recording in the first degree.” In simpler terms, he was bootlegging tapes. A bank is in the space today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

175 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 175 West 72nd Street aka 261-267 Amsterdam Avenue:

Meet Maurice and Micaela of GOLDMINE!