Four Architects and One Roe Mansion

by Tom Miller

On December 13, 1861, Albert Seeley Roe married Rhuamy (known to friends and family as Amy) A. Chamberlain in the parlor of the bride’s parents at No. 432 4th Street. The young groom would soon become successful in the lard refining business and a partner in Chamberlain, Roe & Co.

In the decades following the Civil War, as the Roes established their family, both the Upper East Side and West Side saw a flurry of development. Albert and Amy chose the West Side, and in 1883 were living at 337 West 58th Street. That year would be tragic for the family when 12-year old Jessie Carpenter Roe, their second daughter died of “brain fever” on Sunday May 27.

Three years after the tragedy, Albert Roe set architect Arthur Bates Jennings to work designing a rather monumental rowhouse at 174 West 72nd Street. Architects working on the Upper West Side at the time flexed their creative muscles to create wonderfully playful upscale residences.

The Roe mansion was completed two years later in 1886. Jennings produced a stone-fronted house that refused to be forced into stylistic box. Romanesque Revival coexisted with a touch of Flemish Revival, topped with a slate-covered mansard roof. The house sat above a tall English basement. No two openings were alike and the architect skillfully incorporated arches, gables, engaged columns and carvings to achieve his four-story fantasy.

Albert Roe was considered a leader in the New York lard refining industry. A few years earlier, when reports circulated that lard additives like tallow, water and cottonseed oil were being added to the product, reporters sought out Roe’s opinion. Roe insisted that it was not New York refiners to blame. Although adulterating lard was indeed a common practice, the inferior product was intended for “the Cuban and West Indian trade;” not for Americans.

“The trouble about the adulteration of lard,” said Roe, “originates with the lard-renderers like Armour & Co., of Chicago, and other firms in the West, and not with the refiners, who are as much annoyed by it as are the consumers.”

With Amy and Albert in the new home where their sons, Alexander, Irving and Frank; and two daughters, Laura and Aurelia. The mansion was the scene of a happy reception on February 12, 1896 following the wedding of Laura Bosworth Chamberlain Roe to Henry Burr Anthony in St. Agnes’s Chapel on West 92nd Street.

A few years earlier, when reports circulated that lard additives like tallow, water and cottonseed oil were being added to the product, reporters sought out Roe’s opinion. Roe insisted that it was not New York refiners to blame. Although adulterating lard was indeed a common practice, the inferior product was intended for “the Cuban and West Indian trade;” not for Americans.

Young Alexander Vinton Roe was sent off to Princeton University where he should have graduated in 1895. Known as “Shad,” he did not make it through his sophomore year; and instead dropped out to go into business with his father. He was made a member of Compton & Roe before leaving to start his own firm.

In 1901, Albert commissioned the highly-regarded architectural firm of Janes and Leo to update the residence. The changes, according to The New York Times, on April 25, would cost him $1,500—or about $40,000 today.

Alexander was still living with his parents around this time. He gave up on his own brokerage office and returned to what was now Millet, Roe & Hagen. The Princeton University Decennial Record tactfully said he “Finally has achieved the dignity of being the Board member of Millet, Roe & Hagen, a good firm, with offices in the Drexel building.” The Record added the tongue-in-cheek comment “Roe is, and always has been, an amateur of good horses, and if he ever gets married he is going to send his boys to Princeton.”

Next door to the Roes lived Dr. Julian P. Thomas. Both Thomas and his wife were well-known amateur balloonists and their home was a popular attraction for tour busses—known as “rubberneck wagons.” As each bus passed, its guide would announce the aerialist’s home. It was an annoyance to the residents of the upscale neighborhood, not the least of which was Alexander Roe.

On January 10, 1907 The Sun comically described a guide’s narrative. “Onr lef twe’ve th’ome uv Dr. Julian-thomas thwell known ballonster. Tha’s doctor settinon th’ stoop in thewhite duck soot!”

Alexander complained to the reporter “And then the doctor stands up and bows to the applause of the jays on the rubberneck wagon.” The broker was as much irritated with the doctor’s response as with the tourists. “Some summer evenings the doctor isn’t home. He used to go down to a roof garden when the Fays were in town and often responded to requests for some of the audience to come upon the stage to help the Fays with their experiments. But on other evenings, when he is on the steps, he bows gracefully to the plaudits of the rubber wagon. It’s very annoying.”

Despite the aggravation of a celebrity neighbor, the Roes stayed on in their stone residence. It was there, on November 19, 1916 that Amy Aims Chamberlain Roe died at the age of 78. Her funeral was held in the house on December 1. Less than a year later, on August 3, 1917 83-year old Albert died in the house.

Completed a year later, the alterations had removed the stoop to create what the Department of Buildings termed a “store.” Above were “not more than 15 rooms to be used for sleeping purposes.”

The converted mansion quickly filled with tenants. On February 1, 1919 The Sun reported that the Piccadilly Tea Room had taken the street level. In April the second floor became home to La Vera Shop; and apartments were leased to tenants like Henry Tilden Swan and Jerome Rosenberg. In reporting on Rosenberg’s lease, The Real Estate Record & Builder’s Guide said on March 29 “This completes the rending of the entire building, all leases having been closed within a period of sixty days.” For the 3-room apartments tenants paid from $1,200 to $2,500 a year in rent—about $1,200 to $2,300 a month in today’s dollars.

The Piccadilly Tea Room remained in the space for several years. But by 1935 it has been converted to a pharmacy. It was here on December 1 that year that 63-year old Harry C. Krowl, head of the English Department of the College of the City of New York, suffered a fatal heart attack. The bachelor’s identity was confirmed by the manager of the Ansonia Hotel where he lived.

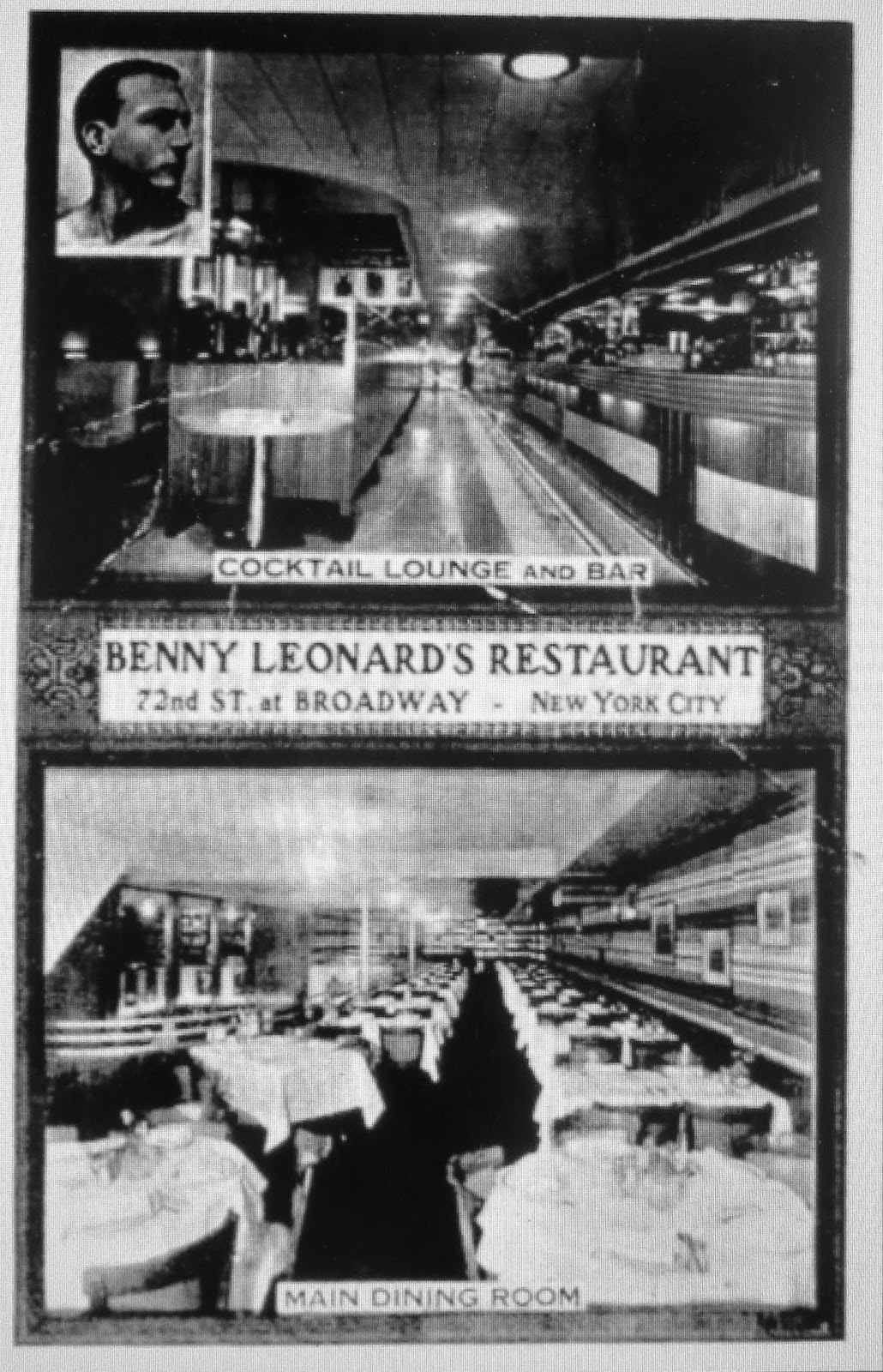

Four years earlier boxing champion Benny Leonard, known as the Ghetto Wizard, had embarked on an ill-advised comeback. That endeavor lasted one year before it was ended on October 7, 1932 by a TKO by future champion Jimmy McLarnin. The former champ now looked for another means to market his name. In 1937 he leased the lower three floors of the former Roe mansion as the site for a restaurant.

The architectural firm of Charles N. & Selig Whinston transformed what had been the Piccadilly Tea Room and then a drugstore into a sleek, ‘30s modern interior. On July 19, 1937 The Times reported on its opening. “The bar and grill is located on the street floor. On the second floor, which has been converted into an oval mezzanine, is the restaurant, with its east wall covered with mural paintings. Features of the place include air-conditioning, indirect lighting and acoustic-treated ceilings.”

Four years earlier boxing champion Benny Leonard, known as the Ghetto Wizard, had embarked on an ill-advised comeback…then in 1937 he leased the lower three floors of the former Roe mansion as the site for a restaurant.

The pugilist-turned-restauranteur found himself in court on January 7, 1938 after he accosted a waiter over a baked potato. Louis Sacoff sued Leonard saying the former champion “had punched him for taking the potato for dinner on New Year’s Day.” Sacoff, described by The New York Times as “a tall and heavy waiter,” had made himself lunch—“a plate of pot roast, together with the disputed baked potato.” He testified that Leonard punched him “in reproof for extravagance in taking the potato.”

Leonard was smug in his own defense. He told the judge, “If I had hit him, he wouldn’t have been able to come for a summons.” The judge dismissed the case.

Benny Leonard had less success in operating his restaurant than he did in the ring or in court. On November 8 that year The Times reported “The store, mezzanine and basement in 174 West Seventy-second Street, where Benny Leonard, the former pugilist, once operated a restaurant, has been leased to Louis Schindler and Paul Landau, who will open a bar and grill.”

Throughout the remainder of the century, the lower floors would house a restaurant and the upper floors “furnished rooms.” For decades the street level was home to Donohue’s, described by one publication as “an Irish dive bar.” Jack Donohue died in 1995 and four years later Paul Hurley, an Irish immigrant, opened PD O’Hurley’s in the space.

A bit more polished than Donohue’s, PD O’Hurley’s was a popular spot for sports fans, tourists, and ale and beer drinkers in general. The routinely good food made it a well-liked neighborhood spot. Then, as with many small Manhattan businesses, the landlord increased the rent to the point that PD O’Hurley’s had to surrender. On January 15, 2013 it closed its doors after 15 years.

Today the pub is still vacant; on the second floor is the Fred Astaire Dance Studios and upstairs are still small apartments. Although the unfortunate brick addition that obliterated the two lower floors could never have been attractive; the upper three floors survive—a reminder of when this stretch of West 72nd Street was lined with architecturally eccentric upscale homes.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

174 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 174 West 72nd Street:

Meet Darius & Jolanta Mosteika!

Meet Linda Hopper and Carrie Galvin!