View of 167 West 72nd Street from south. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Fighting the Firefighter

by Tom Miller

The high-stooped rowhouse at 167 West 72nd Street was completed in 1884. For years it was home to the wealthy Otto S. Cockey family. Cockey was general agent of the Grand Trunk Railway System. In January 1908 he was called to serve on the jury in the trial of Harry Kendall Thaw, who had fatally shot architect Stanford White. But, according to The Evening World, “The fact that Otto S. Cockey, of No. 167 West Seventy-second street, had been associated with Thaw’s father in business barred him.”

At the time of the trial, the West 72nd Street block was still one of elegant private mansions. But change was on the near horizon. Cockey sold the house a few months later to developer Alvan W. Perry. The new owner hired architect E. Wilbur to drastically remodel it to bachelor apartments and commercial spaces.

Wilbur removed the stoop and pulled the façade forward to the property line. The upper floors were clad in deep, red brick and trimmed in limestone. The architect drew from the currently popular Colonial Revival style, giving the openings splayed lintels and keystones. The rusticated stone framing of the two-story commercial base carried on the theme with a layered, splayed keystone.

The ground floor space was leased to Madame M. Obry’s dry cleaning and dyeing establishment. Madame Obry was, in fact, Mrs. Nora Rooney, and this would be her second location, the original being in Grand Central Terminal.

There was one apartment plus the commercial space on the second floor. That space was leased to Dr. Henry J. Swoboda. His operation could not have been more different from Madam Obry’s. On July 23, 1910, The Richmond Hill Record reported he had established a laboratory “for chemical and bacteriological analysis of water, food, contents of stomach, sputum, pathological tissues and makes examination of blood and urine a specialty.” The article added, “The laboratory and office is elaborately furnished and is equipped with the latest microscopes and apparatus for scientific research.”

The 30-year-old had a long list of previous burglaries and the judge had lost his patience. Hamilton was sentenced to five years in Sing Sing for the attempted burglary.

Dr. Swoboda and his family lived in the rear apartment on the third floor. There were two apartments each on the upper floors—front and back. They held either two or three rooms plus bath. Because it was still an upscale neighborhood, the rents ranged from $660 to $900 per year, or about $2,108 a month for the most expensive.

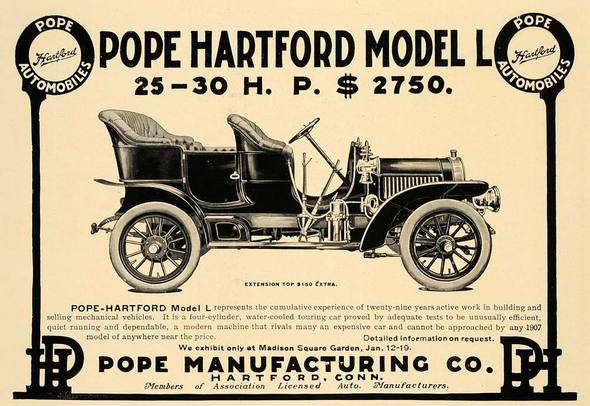

Among the initial occupants was H. Emil Holt, president of the Pope-Hartford Automobile Company. Around December 10 the wealthy bachelor’s automobile was stolen from the curb in front of the building. And then, only a few nights later on December 19, he went out, only to find his apartment rifled when he returned. He was a veteran of the Spanish-American War and almost immediately upon walking in he noticed his service medal was missing. The New York Herald reported, “Other valuables taken were a $300 gold stop watch and a solid gold automobile model worth several hundred dollars.”

Two years later Charles Hamilton was caught in the act of burglarizing another apartment. He had a silver watch and match box in his possession when arrested. The 30-year-old had a long list of previous burglaries and the judge had lost his patience. Hamilton was sentenced to five years in Sing Sing for the attempted burglary.

The prospect of more time behind bars seems to have been too much for him. On June 23, 1912, The Sun reported, “Hanging by a black four in hand necktie from the top crossbar of cell 128 in the Tombs, a keeper found the body of Charles Hamilton, a burglar, yesterday morning.” Hamilton had pinned a note to his shirt that read, “I never had a chance.”

Early on the morning of October 23, 1913, fire broke out in the cellar of the building. The World reported, “It created a surprising amount of thick, pungent smoke that rapidly spread through the building.” The women working in Madam M. Obry’s rushed to save as many gowns and fabrics as possible. Two of them were nearly overcome by smoke inhalation in the process.

Only the family of Dr. David Orr Edson, who occupied the second floor apartment were able to get out by the staircase. One tenant was not at home and two apartments were vacant. Dr. Swoboda “escaped with his family and several patients by way of the back fire-escape,” said the article. Mrs. Valentine M. Fisher, however, who lived in the front apartment on the third floor, was asleep. She woke only when the fire engines were in front of the house.

She panicked as the thick smoke filled the room. “Instead of trying to get out, Mrs. Fisher started to dress and at the same time began to pack some of her belongings in a handbag,” said The World. The deputy fire chief, who had glimpsed her at the window, sent Fireman Turner up to rescue her. When she did not answer his knocks at the door, he kicked in it.

“His entrance completed the hysteria of Mrs. Fisher and she started for the window. The fireman grabbed her just in time. She turned on him and scratched and bit and fought and screamed with all her might,” said the newspaper. A crowd on the street witnessed Fireman Turner’s struggle with the woman amazed. A ladder was run up and a squad of fire fighters headed up. “Mrs. Fisher fainted as they reached the window and was carried down. Turner, covered with blood from wounds on his face and hands, followed.”

Luckily the fire was confined to the cellar and ground floor. Incidentally, The World remarked, “Mrs. Fischer, when she recovered consciousness, insisted on being attended by her own doctor.”

In 1920 the second-floor office became home to the Temple Scott publishing firm. The company focused on “books on spiritual revelation,” according to The Publishers’ Weekly on March 26, 1921. That month the firm released The Lotus Leaf, a book of “spiritual healing” by Elizabeth H. Webb.

Now occupying the ground floor was a dressmaking establishment owned by Broadway and radio entertainer Fannie Brice. When her husband, Jules “Nicky” Arnstein, was accused of being the mastermind behind a series of Wall Street bond robberies, she came to his defense, asserting that the charges were preposterous. “My husband is not rich,” she told reporters. “The fact is that he had hardly any money.”

The fireman grabbed her just in time. She turned on him and scratched and bit and fought and screamed with all her might,” said the newspaper. A crowd on the street witnessed Fireman Turner’s struggle with the woman amazed.

On February 23, 1920 the New-York Tribune reported, “As a side line she has a dressmaking establishment at 167 West Seventy-second Street. She said yesterday in an interview with a reporter for The Tribune that the income from this business, with what she earned on the stage, formed the principal means of livelihood for herself and her husband.”

The comedian’s dress business made way for the Rose Diamont, Inc. shop by 1925. The store sold both custom-made and ready-to-wear dresses for women and young ladies. The second-floor space was now home to the Mecca of Health reducing salon. An advertisement on October 31, 1926 urged, “Reduce sensibly if you’re overweight” and suggested its “high colonic irrigation.”

The building was burglarized again in 1928. Mr. and Mrs. Presley Hamilton had just returned home from their two-week honeymoon in Atlantic City. On July 26 the Daily News reported that “a mean and cruel burglar climbed down the fire escape at 167 West 72d st., entered the honeymoon apartment…and stole every last bit of the trousseau of Mrs. Hamilton.”

The building received a renovation in 1956, but the configuration of commercial spaces and apartments went unchanged. In 1963, Suzy Simpson, a women’s sportswear shop opened in the ground floor space, and by 1976 the New York Hair Center operated from the second floor. In August that year, it introduced “The Ultra Skin Hair Replacement” promising, “No matter how messed nothing is visible! Nothing but hair and scalp.”

The 1980’s saw the Council of New York Cooperatives in the second-floor space and Scuba World below. In 1987 New York Magazine reported that a basic scuba-diving outfit of mask, regulator, wet suit, fins, air monitor and tank could be purchased there for $1,000 (or about twice that much in today’s money).

Today little has changed to E. Wilbur’s attractive 1909 make-over of Otto S. Cockey’s Victorian residence.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

167 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 167 West 72nd Street: