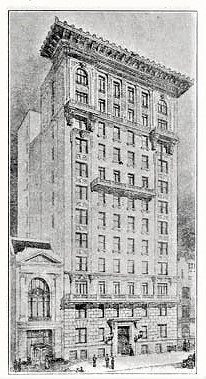

View of 166 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The First to Fall

by Tom Miller

West 72nd Street was developed as a “park thoroughfare,” meaning that the Parks Department was responsible for its maintenance, and that traffic was restricted to only residents and tradesmen who had business there. That all began to change in 1911. The 1921 book Ye Ole Settlers’ Association of Ye West Side recalled:

On February 26, 1911, Mr. Warren Cady Crane, while walking through Seventy-second Street, noticed that house wreckers had begun to demolish the two large brown stone residences at 164 and 166 West Seventy-second Street, near Broadway. It was the first attack—since followed by many others—made upon the old-time private homes in the block, for the towering multi-family house.

The two mansions had been purchased by real estate operators Brown Brothers, Inc. The firm hired George and Edward Blum to design a modern, 12-story apartment building on the site. On August 19, 1911, the Real Estate Record & Guide noted, “The house will contain forty-six housekeeping apartments of three and four rooms, and two doctors’ apartments. Each apartment will consist of a foyer, a large living-room and a chamber, with a large bathroom and kitchen, and in the four-room apartments a dining-room, also.”

The article called the style of architecture “pure Italian Renaissance” and noted, “The lower two stories are of limestone, richly rusticated, the shaft of the building is of blue white brick, with terra cotta bays.” The two floors below the deeply overhanging copper cornice were richly embellished with terra-cotta.

Because they were all one-bedroom suites, servants’ rooms were available in the basement. Maid and valet services were provided by the management. Rents for the apartments ranged from $960 to $1,250 per year—or about $2,750 per month in today’s money for the most expensive apartment.

It was the first attack—since followed by many others—made upon the old-time private homes in the block, for the towering multi-family house.

Living here in 1915 was Jose J. Ramos, described by the New-York Tribune as “a wealthy exporter.” He was arrested in August that year on charges that he had threatened to kill Mrs. Evelyn Rosenberg in a Broadway restaurant. In court she explained that since her marriage to Samuel Rosenberg on February 22, “Ramos had made several unsuccessful attempts to make appointments with her.” Then, on the afternoon of July 23, she was him in an automobile at Times Square. He said he had a letter from her mother which he would not give her unless she accompanied him to a restaurant.

She testified, “When we got to the place Ramos said he was going to keep me away from my husband. He had a gun in his hand and said there were six cartridges in it which would put me away. I begged him not to do anything rash.” She said the two had a cocktail, “then everything became dark.”

But when cross-examined by Ramos’s attorney, Mrs. Rosenberg admitted to having received sums of money from him since her marriage, and while her husband was gone to Panama on business Ramos had paid for a three-day trip to Point Pleasant, New Jersey. Telegrams from her to Ramos were introduced as evidence. One asked him to send her a train ticket because she had had “a spat with her husband,” another asked him to meet her in Chicago. Finally, the judge refused to hear any further testimony and sent Ramos home.

From 1916 through 1918 gambler Julius Wilford, alias “Nicky” Arnstein, leased an apartment here, although it was not for himself, but for his mistress, Ziegfeld Follies star Fannie Brice. In 1918 Arnstein’s wife, Carrie, sued him for divorce and sued Fannie for alienation of his affection. Her suits alleged that her husband and Fannie Brice had committed “acts” throughout the three years in the apartment. Following the divorce Arnstein and Brice were married and lived elsewhere.

In 1920, Jack Clifford Montagni leased an apartment. He was the husband of chorus girl and model Evelyn Nesbit whose earlier affair with Stanford White had resulted in her first husband murdering the architect. In 1916, following her divorce from Harry Kendall Thaw, she married Montagni, her former dancing partner.

Like Nicky Arnstein, Montagni leased the apartment for extra-marital purposes. In June 1920 Evelyn sued him for divorce, claiming that from January to June that year he had “received” motion picture actresses Juanita Hansen and Ann Luther at the apartment where they engaged in “misconduct.”

The building was, of course, more than an illicit love nest. At the same time, upstanding residents like Sir Ernest Manifold Raeburn and his wife, the former Greta Mary Alisson called it home. Born in 1878, he was the son of Sr. William H. Raeburn, and was living in New York as special representative of the British Ministry of Shipping. The couple had two young children, Bigby and Patricia.

Broadway producer Rufus Le Maire also lived here at the time. In 1920, Marcelle Barnes, the star of his show Broadway Brevities, became seriously attached to a wealthy garment manufacturer, Samuel Smith. The New York Herald reported on November 13, “Mr. Le Maire…was one of the first to know of the romance of the actress and Mr. Smith. He offered his home at 166 West Seventy-second street for the wedding and there it took place.” Le Maire may have offered his apartment for the ceremony, but he did not go so far as to give his star the night off. “The bride was in the company as usual last evening,” said the article, “[with her] husband in the front row.”

Rufus Le Maire possibly met fledgling actress and singer Deanna Durbin through another resident. Spanish operatic bass Andres de Segurola lived here at the time. He was with the Metropolitan Opera Company from 1901 to 1920, and now taught singing. Among his pupils was Deanna Durbin. It was Rufus Le Maire who took Durbin to Hollywood where she became a star, making 20 films for Universal Pictures.

Andres de Segurola soon became engaged to Anna Fitziu, an “American beauty and opera singer,” as described by The Evening World. But unfortunately, the bride-to-be decided to put her profession before romance. She told a reporter in March 1922 “The career must go on, although the heart is broken. The very day I ended my engagement, which was January 6, to be exact, I had to sing at a concert in the Biltmore.” But it was not all about career, apparently. She added, “Mr. de Segurola is a Spaniard, and I am, as you know, an American, and the result was a lack of harmony which could not be endured.”

Le Maire may have offered his apartment for the ceremony, but he did not go so far as to give his star the night off. “The bride was in the company as usual last evening.”

In 1930 architect A. I. Seiden was commissioned to make renovations to the building, which included inserting a commercial space into the ground floor. The shop was home to the Saru Bootery in the late 1950’s and became the Windsor Camera Exchange in 1964.

Living here that year was composer Vincenzo DeCrescenzo. He was a friend of operatic tenor Enrico Caruso, who sang his music. When Caruso left the Metropolitan Opera Company, he gave DeCrescenzo’s name to its management so the composer would be admitted free. Other singers who recorded his songs were Tito Shipa, Richard Tucker, and Beniamino Gigli.

Another operatic figure living here in the 1960’s was Doris Doree, who sang with the Metropolitan City Center and Covent Garden Operas. She made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1942. She died while living here in October 1971.

Today a Dunkin’ Donuts occupies the eastern shop space. In October of 2021, My Pie Pizza and Juicy Cube Juice Shop vacated the western storefronts. Other than replacement windows, the handsome structure—the “first attack” on the upscale residential neighborhood in 1911—is virtually unchanged.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

166 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 166 West 72nd Street: