Forbidden Engagements & Explosive Bouquets

by Tom Miller

On July 25, 1885, The Record & Guide reported “The erection will be commenced immediately of the five four-story and basement brown stone dwellings to be built for George J. Hamilton on the south side of Seventy-second street, between Ninth avenue and the Boulevard.” (Ninth Avenue would soon be renamed Columbus Avenue and “the Boulevard” was the current name for Broadway on the Upper West Side.) The architects, Thom & Wilson, estimated the cost of the project at $90,000—or just under $500,000 for each house in today’s money.

Among the group was 158 West 72nd Street, a delightful blend of the Renaissance Revival and Queen Anne styles. The upper façade was splashed with charming elements—carved half bowls below the third-floor windows, an angled oriel crowned with cast iron cresting at the second, and intriguing, small arched openings, a handsome shell carving and classical pediment, among them.

It was purchased in 1891 by Robert Franklin Adams and his wife, Rachel. Adams was a partner with his brother Henry in the fabric manufacturing firm of R. & H. Adams. Founded in 1828 it was now one of the eight largest fabric makers in the country.

Robert, Jr. drew the family’s name into the newspapers in 1894 over his romance with Lena O’Brien, the daughter of wealthy contractor and former assemblyman John O’Brien. Robert was 21 years old and Lena just 16. On March 22, 1894, The Pokeepsie Evening Enterprise [sic] reported “For some time Mr. Adams had been attentive to Miss O’Brien, his visits numbering four or five a week. To say nothing of a Sunday afternoon call.”

For some reason Robert’s parents “disliked the O’Briens and refused their consent to the engagement.” Rachel apparently became suspicious when Robert was not home at 10:00 p.m. on March 18. The New-York Daily Tribune reported a carriage pulled up to the O’Brien house and three women—Rachel and her daughters–rushed up the stoop. John O’Brien answered the door and Rachel demanded to see her son. He refused and ordered her away. When she averred she would not leave without talking to her son, O’Brien called to a passing policeman, ordering him “Throw these people out.”

For some reason Robert’s parents “disliked the O’Briens and refused their consent to the engagement.”

The officer explained to Rachel that since Robert was 21 years old, he could not make him leave. Then, as the women started to leave, a hint at the source of the Adams family’s disdain for the O’Brien’s appeared. The New-York Daily Tribune reported, “Mrs. Adams, with a sign, turned to go, but stopping short and addressing Mrs. O’Brien, made a remark about a family member of the O’Brien family.”

“’It’s false!’ exclaimed the O’Briens in a chorus.

“’It’s true! Returned Mrs. Adams, holding up the portrait of a child.”

Robert remained overnight in the O’Brien house and the following day the pastor of St. Matthew’s Protestant Episcopal Church arrived to marry the young couple. The New-York Daily Tribune noted that the newlyweds left for Chicago and “when they return, will make their home with Mr. O’Brien.”

By 1898, the house was home to Hovhannes S. Tavshanjian and his wife Arax. Born in Constantinople in 1864, Hovhannes had come to the United States as a representative of a Turkish rug business. He eventually started his own business and by the early 1890’s, according to the American Carpet & Upholstery Journal, was “doing a business of nearly a million dollars a year.” His firm was one of the largest Turkish rug importers in America.

Two daughters would be born to Hovhannes and Arax in the West 72nd Street house. Arpinee was born on August 20, 1902 and Ardemis on June 18, 1904.

Travshanjian walked a political tightrope when it came to Turkey, where his goods originated. He was an Armenian by ethnicity, a group that had been under Turkish control for centuries. American Carpet & Upholstery Journal said, “His purse and heart, it is said, were always open to any struggling Armenian.” He was tortured because, as he told a reporter, “Turkish authorities will not permit me to come back to Constantinople, and my own people believe that I am pro-Turkish in my views.”

By 1907, Travshanjian was the wealthiest Amenian rug merchant in the United States with a fortune estimated at more than $42 million by today’s standards. His political outspokenness was dangerous, and he became the target of would-be blackmailers connected with the Armenian Revolutionary Society that year.

At 1:00 on the afternoon of July 22, 1907 Hovhannes was returning to his store at 33 Union Square. American Carpet & Upholstery Journal reported that just as he entered the lobby of the Century Building, he was attacked. “The assassin, who had been lying in wait for Mr. Travshanjian, crept up behind him and shot him twice in the back, causing instant death.” The journal added, “Mr. Tavshanjian’s murderer was a poor imbecile Armenian who was supposedly the tool of a gang of blackmailing Armenians.”

Travshanjian’s funeral was held in the West 72nd Street house under tight security. The Evening Enterprise reported “Previous to the funeral the widow of the millionaire Armenian rug importer received a letter which stated that one or all of the members of her family would be killed, if not during the funeral services, then, the note said, the threat would be executed subsequently.” More than 20 suspicious looking men were refused admittance and were “hustled away by the detectives,” said the article, noting “Even bouquets of flowers were turned away for fear that might contain bombs or explosives.” Happily, the funeral “passed off without bomb throwing or murder.”

Arax and her daughters remained at 158 West 72nd Street until 1919. By then the block had drastically changed as private houses were being converted to businesses and apartments. Arax leased the house for a term of 21 years “to a company which will alter it into stores and apartments,” wrote The Record & Guide.

The stoop was removed, and a two-story commercial front installed. The ground floor space became home to the Caledonian Tea Room where “genuine old fashioned Scotch breads” could be had and Afternoon Tea was served from 3:00 to 5:00. Prix fixe dinners cost $1.25 (just under $16,00 today). The second floor was leased to the real estate firm Welling & Koelble, Inc.

“Even bouquets of flowers were turned away for fear that might contain bombs or explosives.” Happily, the funeral “passed off without bomb throwing or murder.”

The top three floors were converted to apartments. An advertisement in 1922 described them as “exceptional suites,” each two or three rooms with bathroom and kitchenette. Rents ranged from $840 to $1,800. (The most expensive would equal about $2,500 per month today.)

In 1924, the second floor was converted to a lecture hall known as the Oasis. Grace Ellery Williams’s subject matter was a blend of religion, spiritualism, and astrology. On July 20 that year, for instance, she spoke on “Astrology in the Bible.” Her topics in August were “The Spirit of Neptune,” “What Jupiter Does for You,” “The One-Eyed Giants,” and “Your Astrological Chart.”

With the repeal of Prohibition, in 1935 the former ground floor tearoom became the Delmont Tavern, which routinely advertised in Irish-American newspapers. It gave way to a restaurant, once again, by 1964 when Casa Delmote occupied the space.

Upstairs, where once Grace Ellery Williams had held sway in the Oasis, jazz lovers packed in to Palsson’s Jazz bistro in 1980. John Corry, writing in The New York Times on January 3, 1981 rejoiced that the club was resurrecting Sunday “jazz matinees,” once popular in the 1950’s. He noted, “Palsson’s sells booze, but if you don’t want to drink, it offers food, too.”

The following year, on January 29, Rex Reed critiqued Forbidden Broadway in the Daily News. Among his comments he said, “In the upstairs cabaret room at Palsson’s, a charming restaurant at 158 West 72d St., you are not halfway through dessert when the cast appears among the diners, singing their hatred of Broadway,” and “One of the show’s most undeniably truthful outrages is Patti Lupone singing ‘Don’t cry for me Barbra Streisand / the truth is I never liked you.”

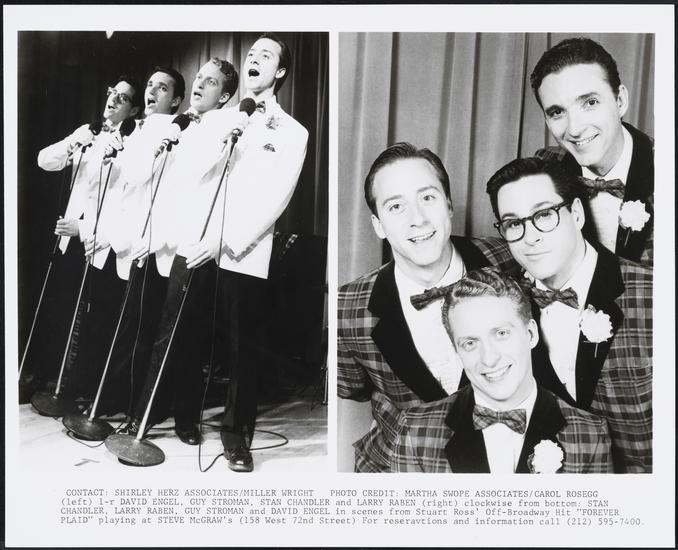

Palsson’s remained until 1989 when Steve McGraw’s Place took over the second floor. Like Palsson’s, it offered cabaret shows. In 1991, New York magazine described it as “a supper club that consistently presents topnotch cabaret reviews.”

Steve McGraw’s Place was replaced in 1995 by the Triad Theater, the third cabaret in a row in the space. Its staging of Spamilton in 2016 prompted The New York Times to glow, “Contrary to what its rabid fans might believe, the juggernaut hit ‘Hamilton’ is not the only musical that ever mattered.”

The Triad Theater is still in 158 West 72nd Street today, above (somewhat ironically given the building’s history) a Turkish Restaurant. A glance at the top three floors provides a glimpse into the 1890’s when this block was home to some of Manhattan’s wealthiest families.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

158 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 158 West 72nd Street:

Meeet Peter Martin!