Hypnotism by Mail Order!

by Tom Miller

The glory days of the once-residential West 72nd Street had been over for more than a decade in August 1922 when real estate operator Harry Alperstein leased the two 20-foot wide brownstone houses at 153 and 155. He signed a 53-year lease, telling the press he intended to “erect a seven-story office and store building on the site,” as reported in the New-York Tribune.

He commissioned the architectural firm of Springsteen & Goldhammer to design the replacement building. Completed in 1923, the brick-faced structure was a mixture of styles—Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Romanesque predominating. The windows of the four-story midsection were flanked by shallow piers and connected by three picturesque rows of arched corbels. The more formal uppermost floor was clad in limestone and capped by a bracketed cornice.

On March 18, 1925 The New York Times ran an innocuous notice:

Edward W. Browning, realtor, is moving his headquarters…to commodious offices in the new office building at 153 and 155 West Seventy-second Street, just off Broadway. Mr. Browning is the owner of the World Tower and Herald Square Buildings, as well as many uptown hotels, &c.

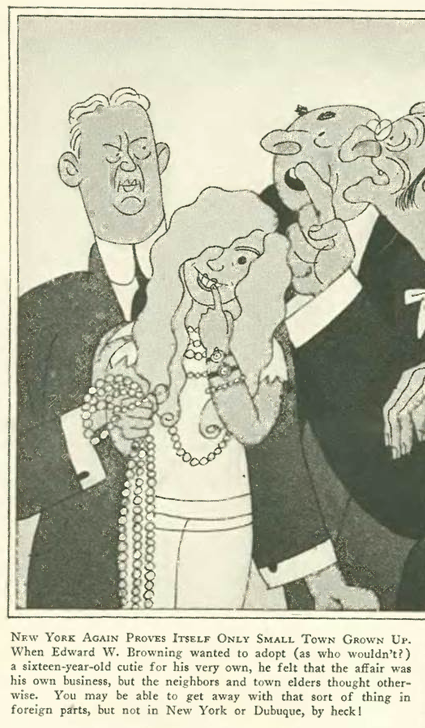

The millionaire had built impressive buildings around New York, including two on West 72nd Street–the identical Hotel Earlton and Royalton Hotel, both of them “apartment hotels.” Browning’s penchant for younger—much younger—women would bring unwanted publicity to 153-155 West 72nd Street.

It started soon after he moved in, when he placed an advertisement in newspapers that read “Wanted—Girl for Adoption.” Mary Louise Spas, a daughter of Bohemian immigrants, saw the ad. According to The Daily Star on August 5, 1925, “Without telling her parents where she was going, and with only five cents in her pocketbook, she went to his office in Manhattan…She found a line of applicants in the office before her, and many more made their appearance afterwards.”

Browning’s interest in his two “daughters” dimmed when he met 15-year old Frances Belle Heenan. The 51-year old real estate man married the girl he called “Peaches” on April 10, 1926.

Mary Louise was one of 12 girls Browning approved for “trial adoption” and on August 4, the final adoption papers were signed. She was Browning’s second adopted teen-aged daughter. The Daily Star published a photograph of the millionaire with his new ward sitting affectionately on his lap.

Browning’s interest in his two “daughters” dimmed when he met 15-year old Frances Belle Heenan. The 51-year old real estate man married the girl he called “Peaches” on April 10, 1926. Two days later, according to the Daily News, “While his wife was touring about, attracting no attention, Browning was besieged in his office at 155 West 72d st., by an army of women and girls, who wanted ‘only one glimpse’ of the famous Cinderella man.”

Although Browning was totally infatuated, the marriage was headed for trouble. Before the end of the year Peaches had left “Daddy Browning,” and in December Mary Louise Spas (called “the original Cinderella girl” by the press), sued him for $500,000. She claimed attempted assault and threats against her and her parents (who had managed to have the adoption annulled).

The hearings for separation, which commenced on January 24, 1926, gave reporters more than enough scandalous details for their readers. While Browning explained that he took Peaches shopping in his blue limousine and “took her to every show in town, to dances and social functions,” she accused him of keeping a live goose in the bedroom, forcing her to remain nude in the apartment, and tossing telephone books at her.

As it turned out, the courts decided that Frances had abandoned her husband “without cause.” That was no consolation to Browning and on October 7, 1926 The New York Sun reported, “Browning, heartbroken at the sad ending to his dream and moping in his office, 155 West Seventy-second street, yesterday figuratively took up the trail of his vanished Cinderella with a glass slipper in the form of an announcement that he is maintaining both a town resident at the Hotel Emerson and a country home at Kew Gardens for ‘Peaches’ if she wishes to return to either of them.”

While the drama played out on the ground floor, the many of the tenants in the upper story offices, like Browning, were in the real estate or construction field. Among them were architects Lilien & Lilien, the commercial painting and decorating firm of John Edwards, and Psaty & Furhman, Inc., “masons, builders and general contractors.”

The office of the General Council of the Retail Cleaners and Tailors Association was located here in 1934 when a city-wide strike of dry cleaners was initiated. A series of meetings on February 19 organized “a march of at least 20,000 men to City Hall,” according to The New York Sun.

By 1936, Esther Reis was leasing the ground floor space. A custom women’s tailor, she specialized in what she termed the “hard-to-fit” customer. She had a quick answer for women who might have thought twice about the expense of a custom garment. She told reporter from the New York Post, “if a blouse doesn’t fit it’s a total loss, no matter how much or how little you paid for it.”

A less respectable, albeit probably equally lucrative, business operated from an upper floor office in 1936. The illegal gambling came to an end when it was raided on the night of February 4. Nineteen men were arrested in what police called “an alleged wire room.”

She had a quick answer for women who might have thought twice about the expense of a custom garment. She told reporter from the New York Post, “if a blouse doesn’t fit it’s a total loss, no matter how much or how little you paid for it.”

One rather questionable tenant in the mid-1940’s was the Silhouette Salon, which promised a beautiful body without the annoyance of working out. An advertisement on April 30, 1945 read:

This is the newest, practical approach to a beautiful figure without dieting, steaming or exercise. You remove your hat and coat, nothing more, and relax. This new modern method of contouring, multiple oscillation, slims enlarged thighs, ankles, spreading waistline, double chin and flabby tissues.

The fact that the Silhouette Salon lasted only about two years may testify to the success of the treatments.

Ralph Slater leased a one-man office here in 1946 (like Silhouette Salon, he would not last long). Calling himself a “world famous hypnotist,” he promised to teach hypnotism by mail order with only a few hours study “in your own home.” By knowing how to hypnotize, said his ads, you could “make new friends, develop self-confidence,” and “correct bad habits.”

A renovation completed in 1949 for a restaurant resulted in a new storefront. The second half of the century saw a different type of tenant in the building. In 1963, the Language Center was on the third floor. In addition to courses in English for new arrivals to the United States, it offered free courses in American Citizenship.

By 1964 Tip-Top Shoe store took over the ground floor space and is still operating there more than half a century later.

New York City’s Office of the Aging opened the Crime Victim’s Assistance Center here in 1976. Counselors were sent from here to work with elderly crime victims as part of a federally financed program. It additionally held crime-prevention lectures at senior citizens’ centers around the city.

Similar social interest groups continue to lease space in the building. Among them today are the Behavioral Psych Studio, the New York Urban Professionals Athletic League and the Susan Luger Associates (a special education advocacy group).

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

153-155 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 153-155 West 72nd Street:

Meet Lester Wasserman!

Meet Steven L. Goldstein!