Joined Buildings and a ‘Clip Joint”

by Tom Miller

In April 1884, George J. Hamilton announced his intentions to erect five “first-class four-story high-stoop brown stone houses, with all improvements” on the south side of West 72nd Street, “between Ninth avenue and the Boulevard [known today as Columbus Avenue and Broadway, respectively].” His architectural firm, Thom & Wilson, estimated the cost of construction at $120,000—or about $645,000 each in today’s money.

The row, completed in 1886, was designed in a blend of Northern Renaissance Revival and Queen Anne styles. The architects’ two models were repeated in an A-B-A-B-A pattern. Representing one of each were 152 and 154 West 72nd Street. Three bays wide, their elaborate carvings and intricate architectural details reflected the affluence of the families who would occupy them.

Wealthy businessman A. B. Scott purchased 152 West 72nd Street while 154 became home to Morillo H. Gillet. Born in 1821 in New York, Gillet relocated to Ohio in 1843. According to a friend, James H. Anderson, in 1863, “He began life poor, but became rich shipping fat livestock and fresh dressed meats to New York, and England, and by other successful ventures. It is said that one of his sons married a daughter of a brother of the late Commodore Vanderbilt.”

On February 19, 1889, Morillo H. Gillet died at the age of 68. The following year A. B. Scott relocated permanently to Europe. The Gillet house was purchased by millionaire J. Berre King, principal in the J. B. King Plaster & Cement Mills. His plant employed more than 1,000 men. Gillet was best known to New Yorkers as a yachtsman. He owned and raced two sloops, the Neola and the Sybil, the schooner yacht, the Elsie Marie, and the schooner Spasm.

Both houses were sold in 1903. The former Scott mansion became home to the Misses McFee’s School for Girls. Exclusive, private girls’ schools were routinely found in the most fashionable residential districts. This one, run by Dr. Janet Donalda McFee, catered to girls from kindergarten to college age. Boarding was available to students between 8- and 16-years of age. The curriculum focused on grooming the daughters of well-to-do families to smoothly enter polite society. An advertisement noted that the classes included “French, Music, Aesthetic Dancing, Music and Art.” It also mentioned, “Social Advantages.” Living in the house and, presumably, helping with the school were Janet McFee’s sisters, Anna and Katherine.

Sarah Hess’s parents, Isidore and Ida Straus, were returning home on the maiden voyage of the luxury steamship the RMS Titanic. Word arrived at the 72nd Street house that the ship had sunk.

The former King house was sold in April 1903 to Dr. Alfred F. Hess and his wife, Sarah, for the equivalent of $1.2 million in today’s money. Dr. Hess had graduated from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1901. The couple would have three children in the house, Eleanor in 1906, Margaret a year later, and Alfred Selmar, who was born in 1910.

A well-respected physician, Hess made inroads in several areas. It was he who discovered that the factor missing in scurvy was present in citrus fruits and tomatoes. By studying nutrition, he was able to greatly advance the treatment of scurvy and the prevention of rickets. He was, as well, the medical director of the Tuberculosis Preventorium for Children.

The Hesses received terrifying news on April 16, 1912. Sarah Hess’s parents, Isidore and Ida Straus, were returning home on the maiden voyage of the luxury steamship the RMS Titanic. Word arrived at the 72nd Street house that the ship had sunk. Although Sarah’s mother had safely boarded a lifeboat, when she realized her husband could not accompany her, she stepped back on the doomed vessel.

In 1913 Robert Sterling Clark, son of Alfred Corning Clark, purchased 152 West 72nd Street (he already owned 150), and soon acquired 154 as well. By 1915, 154 West 72nd Street was being operated as a musical boarding house. Among the residents over the next few years were singing instructor William S. Brady, violinist Jan Hambourg, tenor Roderick Benton, and pianist brothers Josef and Clarence Adler.

Rumors within the real estate community were that Clark intended to demolish the vintage houses and replace them with a modern apartment building. Instead, however, in July 1919 he sold 152 and 154 West 72nd Street to Joseph Heit & Sons, who quickly resold them to Elmer E. Smathers. The New-York Tribune opined on July 4 that the houses “will probably be altered into apartments and stores.”

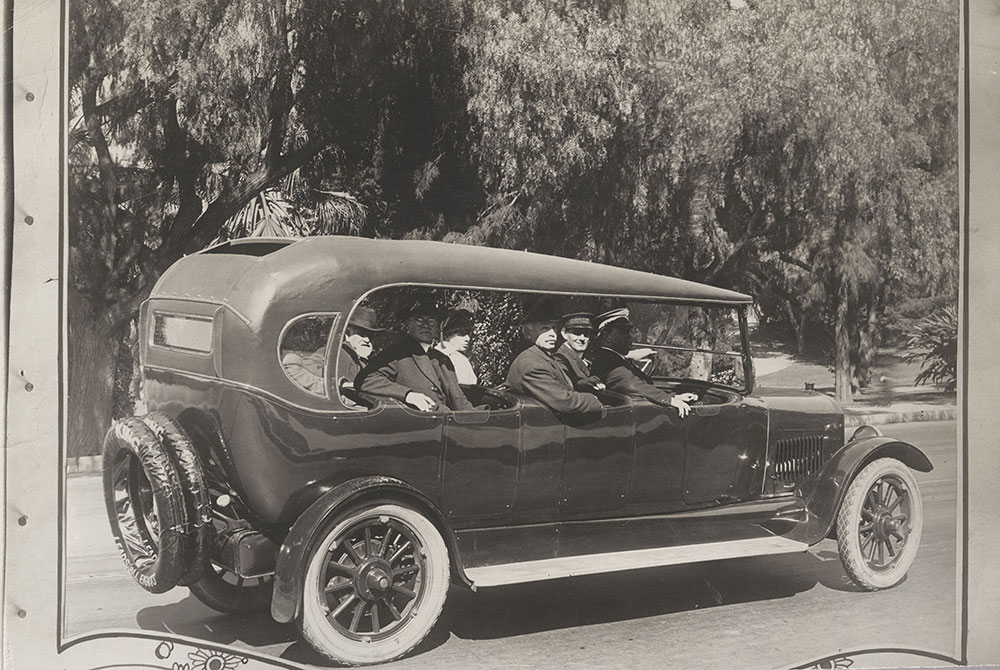

Indeed, The New York Times reported on April 10, 1920, “Two four-story dwellings at 152 and 154 West Seventy-second Street, near Broadway, are to be remodeled into showrooms and offices for the King Car Corporation.” Architect Robert T. Lyons was commissioned to remove the stoops and install a single two-story storefront that extended to the property line. The upper floors were converted to 30 studio and non-housekeeping apartments (meaning there were no kitchens).

The King automobile company was founded in Detroit in 1911. During its best times King automobiles were exported across the world. The shiny cars exhibited in the new 72nd Street showroom had prices tags of about $33,000 in today’s money. But the plan to construct a branch in New York now was bad timing. In the fall of 1920, directors sought to dissolve the company. It was purchased early in 1921, signaling the end of the expensive and brand new 72nd Street location.

With the departure of the King, the store spaces were separated. The New York Telephone Co. moved into the ground floor of 154 West 72nd Street, while Julius Bloom moved his hair salon into the upper space. Bloom was known in the industry simply as Mr. Julius. When the American Master Hairdressers’ Association, Inc. held its convention in the Waldorf-Astoria in March 1924, Greater New York magazine noted that its president was Mr. Julius.

Among the residential tenants in 1921 was 21-year-old stage and motion picture actress Helen Neary McCloskey. She was arrested that November on charges of driving an automobile while intoxicated. Taken before Magistrate House in Traffic Court, she told him he was “too old” to try her case. And so, it was transferred to Special Sessions. Released on $500 bail, she failed to show up for her trial.

She made it to her second trial on April 10, 1922. But it did not go well for the actress. The Evening World reported, “Much to her amazement and chagrin, Miss Helen Neary McCloskey, who says she is a moving picture actress…was to-day in Special Sessions found guilty of driving her motor car while intoxicated.” A physician and the arresting officer testified to her condition. Patrolman Samuel Weinstein added that she had had “something between a Bronx cocktail and a gin fizz.” He also testified that “she said some decidedly rude things to him when he stopped her car.” The newspaper said, “Miss McCloskey frequently interrupted witnesses with exclamations…‘I didn’t do any such thing!’ and ‘That’s wrong; get up and object to it!’”

In 1931, the ground floor of 152 West 72nd Street was a speakeasy, operated by Louis Greenstein. But it was much more than just that. It was what was called at the time a “clip joint.” The term referred to places, which lured out-of-towners, often through the recommendations of paid taxi drivers, and then being charged outrageous amounts for drinks. One patron, Frank S. Long, had two drinks with two bottles of ginger ale on December 3, 1931 and was charged $95—more than $1,500 today.

It was discovered that some patrons would be drugged and taken to rooms upstairs where they were held captive, sometimes for weeks, until they paid the enormous bills.

Another salesman, William H. Turner, testified that he was taken to the place on March 3, 1932. He was “shaken into consciousness by Greenstein” the next morning and told he had signed a check for $100. The check was worthless because Turner had closed that account. The New York Sun reported that according to Turner, “Greenstein called him up several times and that someone, he was not sure who, suggested that if he did not make good, he might lose an ear.”

After a raid in April 1932, evidence against Greenstein worsened. It was discovered that some patrons would be drugged and taken to rooms upstairs where they were held captive, sometimes for weeks, until they paid the enormous bills. In some cases, while the victim was unconscious, Greenstein would bring in a woman and photograph them together for extortion purposes.

On June 9, Federal Judge Frank J. Coleman sentenced Greenstein to three years in the Atlanta penitentiary. He told him, “The reason for the severity of the sentence is not because you ran a speakeasy, but because of the kind of speakeasy you ran…Your type of resort is not wanted in New York nor in any other city.”

By the 1940’s Gartner’s Hardware was in 154 West 72nd Street. In 1966, the Hahn Real Estate office was in 152, joined in the second space in 1971 by Modern Art Furniture. They would be replaced by The Smile Center, a dental office, and Negev Caterers, a kosher foods shop, in the 1980’s.

In the 1990’s the Arclight Theater Company operated from 152 West 72nd Street. It was the scene of a memorial production, Tennessee Williams Remembered, in 1999, starring Eli Wallach and Anne Jackson. Next door, Ivy’s Café opened in 154, replaced by Dark Bullet Sake & Oyster Bar around 2013.

The first and second floors of Thom & Wilson’s lavish homes have all sprouted storefronts. But a glance above reveals what the row looked like when millionaires and their wives lived here.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

152-154 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 152-154 Columbus Avenue: