Unamusing Tax Fraud

by Tom Miller

In offering the house at 144 West 72nd Street for sale in April 1889, developer George J. Hamilton described it as “elegant” and said that in “design, material and workmanship” it was “the very best.” He added that West 72nd Street was “acknowledged to be the finest in the city.”

The house was one of a row of five designed for him by the firm of Thom & Wilson in 1885. The 21-foot-wide residence was faced in brownstone; its imperious Renaissance Revival façade was decorated with tall paneled Corinthian piers, classical pediments over the third floor windows, and a pressed metal cornice.

Hamilton’s advertisement came two years after the house was completed. The following year, on October 23, 1890, it was sold it at auction to James Henry McCoon, whose winning bid was $58,8000—about $1.7 million today.

A stockbroker, McCoon was the son of Cornelius and Catherine Adelia McCoon. Two years before purchasing the 72nd Street house he had married Alice Maude Martin. The newlyweds would have company in their new home. Not only did the widowed Catherine McCoon move in with them, but so did James’s sister, Catherine Augusta.

Alice’s mother-in-law was as socially visible—or more so—than she. On February 20, 1896, for instance, The New York Times reported, “Mrs. C. A. McCoon of 144 West Seventy-second Street gave a luncheon party yesterday, when covers were laid for six persons.”

She had named James the executor of her estate. But his sister and brother-in-law went to court, claiming that he was mentally unbalanced. On January 1, 1906, the courts declared him “to be of unsound mind,” and a month later he was removed as executor of the wills of both his parents.

Around the turn of the century, the younger Catherine married Frederick W. Gunther, increasing the population of 144 West 72nd Street by one.

On November 24, 1905, Catherine Adelia McCoon died in her bedroom, setting off what would be a somewhat bizarre legal battle. She had named James the executor of her estate. But his sister and brother-in-law went to court, claiming that he was mentally unbalanced. On January 1, 1906, the courts declared him “to be of unsound mind,” and a month later he was removed as executor of the wills of both his parents. Frederick and Caroline McCoon Gunther were appointed the sole trustees of the trusts.

There may have been something to the Gunthers’ claims. James Henry McCoon died later that year, on December 9, and his will was somewhat remarkable. It directed Alice “to pay over to his mother, Mrs. Catharine Adelia McCoon, all sums received…in the payment of his life insurance.” The New-York Tribune reported that he also left his mother the proceeds of the sale of his seat on the Stock Exchange. The rest of his estate was divided into three equal parts—bequeathed to his mother and two sisters. Nothing was left to his wife.

Luckily for Alice, because Caroline McCoon was dead the state demanded that “his estate would be distributed as if he had died intestate,” according to the New-York Tribune on December 19. The bulk of the fortune now went to her.

Alice began construction of a handsome townhouse at 109 East 79th Street—one of a matching pair. (Her sister, Edith Martin, built the other.) She transferred ownership of the 72nd Street house to Caroline and Frederick Gunther. The couple did not wait for Alice to move out before initiating major renovations.

They hired the architectural firm of Pickering & Walker to design a three-story extension to the rear, make “interior changes,” as worded by the Record & Guide, and to install a full-width rounded bay at the second floor. The renovations cost the equivalent of $293,000 today.

The Gunthers remained in the house while the 72nd Street neighborhood changed around them. At the time of Frederick’s death on February 17, 1920, theirs was among the last of the private homes along the block. Caroline sold it not long after his funeral (which was held in the drawing room here) to a real estate operator, who wasted no time in converting it for business purposes.

The former McCoon house was joined internally with 140, 142 and 146 to create the St. Nicholas Apartments on the upper floors. The stoops were removed, and a two-story commercial extension erected at the property line.

Real estate operator and builder G. L. Lawrence took the first-floor space in 144 West 72nd Street for his offices in April 1921, and Arthur J. Meyers leased the second floor for his “hairdressing parlor” eight months later. The apartments were not expansive, but on the higher end. An advertisement in 1922 described a “large two-room apartment with bath and kitchenette.”

Among the initial tenants were Herman Broesel and his wife, the former Mary Agnes Lawton. Broesel had graduated from Princeton University in 1908 and was Sales Manager of the Cunningham Motor Sales Company. A member of the New York Athletic Club, he and Mary Agnes owned a summer home at Lake George.

On December 24, 1940, The Brooklyn Citizen entitled an article “Nine Gay Spots Accused by U.S. Of Tax Evasion.” Among them was the West End Grill, accused of “amusement tax frauds,” according to the article.

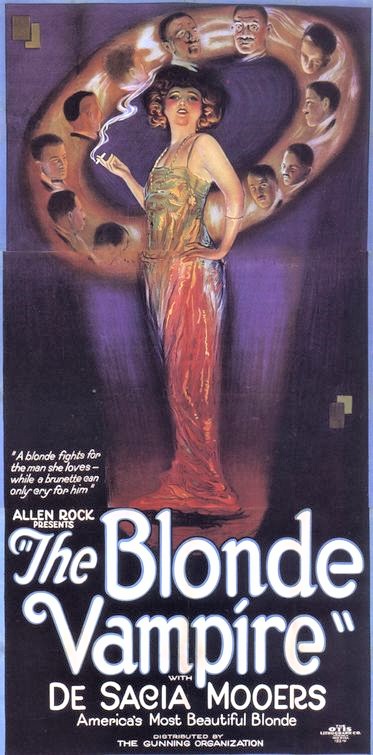

Silent film actress De Sacia Mooers was another early tenant. She was estranged from her husband, Edward Demarest Mooers, owner of the Yellow Aster gold mine in California. Their romance was doomed from the start because his wealthy family disapproved of her career. In 1922 she appeared in the first of a series of “vamp” roles as the lead in The Blond Vampire. She remained in the building at least through 1924.

The apartment of Mildred Mathews doubled as her dance studio. The Brooklyn Citizen reported on February 10, 1929, “You can dance every Friday evening and Saturday afternoon in the refined atmosphere of Mildred Mathews’ Studio at No. 144 West Seventy-second street, New York. Miss Mathews has achieved unusual distinction as a dancing teacher, and offered instruction in ballroom dancing at these social gatherings.”

Following the end of Prohibition, the ground floor space was converted to a tavern-restaurant known as the West End Grill. The innocuous restaurant by day became a more shocking gathering spot at night. On December 24, 1940, The Brooklyn Citizen entitled an article “Nine Gay Spots Accused by U.S. Of Tax Evasion.” Among them was the West End Grill, accused of “amusement tax frauds,” according to the article.

The West End Grill was gone not long afterward. By 1942 the space was home to the Castellanos-Molina Music Shop, known nationally for dealing in Latin-American music, records and sheet music. It remained until around 1953, replaced by the Randolph Radio TV Service.

In the mid-2000’s the store was home to the Always Love Discount Smoke Shop, and more recently to the Wellness Pharmacy. The upper floors of James Henry McCoon’s handsome house—complete with the Gunthers’ striking bay—survive above the 1921 storefront.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

144 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 144 West 72nd Street: