Engagements: Broken and Otherwise

by Tom Miller

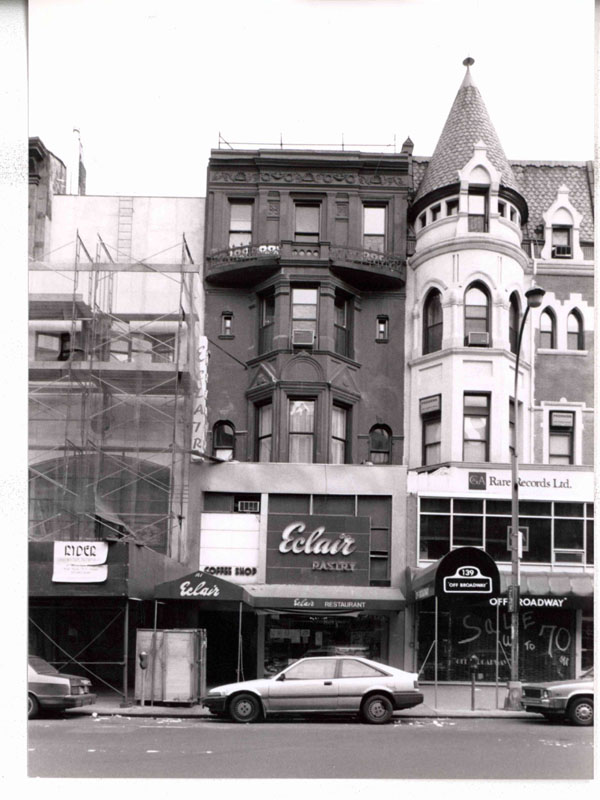

As a flurry of construction took place along West 72nd Street in the mid-1880’s, the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson was kept busy by developers. In June 1885 it filed plans for five “four-story brick (stone front) dwellings for real estate operator Robert Irwin. The high-stoop homes were completed in 1886, with two of them, 137 and 139, stealing the show from their siblings. But 141 West 72nd Street held its own with a brownstone facade liberally trimmed in ruddy terra cotta, a faceted three story bay at the parlor through third floors, and a bowed balcony at the fourth.

Described in an advertisement as a “magnificent four story and basement brown stone dwelling, with dining room and bedroom extension; open plumbing, hardwood trim, parquet floors,” it became home to the Nathaniel Hess family. Hess was a retired woolen merchant. Living with him and his wife were her two children by a former marriage, Mary Britton Leary and Joseph Britton Leary. The family’s name appeared in the society columns regularly.

On December 14, 1893, for instance, newspapers reported that “Cards have been issued by Mrs. Nathaniel Hess of 141 West Seventy-second Street for the afternoons of Wednesdays in January.” (It was necessary for socialites to announce when they would be “at home” to receive so as not to confuse schedules.) And four months later The New York Times announced “Mr. and Mrs. Nathaniel Hess and family…will leave town for Italy on March 17 on the steamer Kaiser Wilhelm. They will remain abroad until late in the Fall.”

Following Joseph Leary’s wedding, he and his bride lived elsewhere. After her death in 1900, he chose to live at his club. Now, in 1902, when he was remarried to Janet Graves Ford, he was 28 years old and vice-president in his father’s brewery, the Leavy & Britton company. The Sun mentioned in its article on the wedding that the bride “is rich in her own right.”

Scotti, who was said by newspapers to be popular with the ladies, did not return to New York that season. There were no doubt many feminine tears in the 72nd Street house before The World ran the headline on December 8, 1903, “Scotti Released From Cupid’s Chain.”

In 1901, Mary Britton Leary, just out of the Convent of the Sacred Heart school, met the opera star Signor Antonio Scotti. Everybody’s Magazine noted “as she spoke little French, and he knew less English, they had not a wide basis of communion.” But in 1903 the magazine wrote “One of the interesting October weddings will be that of Signor Antonio Scotti, the well-known baritone of the Metropolitan Opera Company, to Miss Mary Britton Leary, of New York, daughter of Mrs. Nathaniel Hess.”

But October came and went, and the marriage did not happen. Scotti, who was said by newspapers to be popular with the ladies, did not return to New York that season. There were no doubt many feminine tears in the 72nd Street house before The World ran the headline on December 8, 1903, “Scotti Released From Cupid’s Chain.” The Sun reported “The family of the young woman also refused to say more than that the engagement had been terminated by mutual consent.”

But love was in Mary’s near future. On July 29, 1904 The Standard Union reported that she had “quietly” married Juan de Jara Almonte, Marquis de Casa Jara in Spain. The article described the new marquess as being “of unusual culture, a musician and a linguist.” The couple spent their honeymoon in the country home of Chauncey Olcott and his wife in Saratoga before moving into the Hess home on West 72nd Street.

Hess sold the house in 1905 to Henry Eugene Spadone and his wife, the former Mary Louise Dusenbery. Henry was president and a director in the Gutta Persha and Rubber Manufacturing Company, which manufactured mechanical rubber goods like belting and packing hose. He and Mary Louise had been married since June 1875 and had three children, Henry, Blanche and Amedee. Also moving in with them was Mary Louise’s widowed mother, Emily Adeline Dusenbery.

The Spadone’s most often summered in the fashionable community of Summit, New Jersey; however, they always leased a house there rather than buy one. Following America’s entry into World War I, on April 11, 1918 Mary Louise presented a large American flag to the town in honor of Amedee, who was a captain in the army.

Later that year, in October, the Spadones announced Blanche’s engagement to Samuel F. Adams, Jr. In a déjà vu moment, however, on December 3, 1918 The Sun reported “Mr. and Mrs. Henry Spadone of 141 West Seventy-second street, announced yesterday that the engagement of their daughter, Miss Blanche Spadone, to Samuel F. Adams, Jr., has been broken. No reason was given for the break.”

Mary Louise and Blanche entertained and traveled together after the romantic disappointment. On February 8, 1920, for instance, The New York Herald announced that “Mrs. Henry Spadone and Miss Spadone” were escaping the New York winter weather in Augusta, Georgia.

When Henry Spadone sold No. 141 West 72nd Street to Charles K. Clisby in October 1923, his was among the last of the private houses along the thoroughfare, the others having been razed or converted for business. The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that Clisby “will use it for his brokerage and mortgage business.”

The inevitable came in 1927 when architect Otto A. Staudt removed the stoop and façade of the lower floors to erect a two-story commercial extension. The space would become home to an Upper West Side phenomenon in 1939.

Alexander M. Selinger would operate what was eventually known merely as Éclair for half a century. He sold the business in 1993 and died at the age of 91 five years later.

Alexander Selinger was the refugee son of a Czech father and Italian mother. He opened the Wiener Kaffeehouse Éclair, modeled after the cafes of Vienna. Peter Schrag, in his 2019 The World of Hitler’s Refugees in America, wrote:

It soon was a draw not only for the Viennese immigrants who came, some almost daily, for their pastries and their Kaffee mit Schlag, and maybe a slug of nostalgia, to sit schmoozing with their friends, or even for a full course dinner of Wiener Schnitzel, potatoes, and Kopfsalat. It was also an attraction for a long list of celebrities, many of them Jewish but few of them emigres from the Nazi era—Aaron Copland, Burl Ives, Eddie Cantor, Melvyn Douglas, Jack Palance, Roberta Peters, Richard Tucker, Bruno Walter, and Barbara Streisand.

Alexander M. Selinger would operate what was eventually known merely as Éclair for half a century. He sold the business in 1993 and died at the age of 91 five years later. Upon his death Robert McG. Thomas, Jr. wrote in The New York Times, “They are mostly ghosts now: the Éclair itself, and the throngs of displaced singers, musicians, writers, artists, undifferentiated intellectuals and other culture-shocked refugees who made their way to New York from Nazi Europe in the 1940’s and found instant nostalgia, animated conversation and sometimes even love over a schlag-slugged cup of coffee and perhaps a nice piece of Éclair strudel.”

Almost as a slap in the face, a year before Selinger’s death a Krispy Kreme store opened in his former café. In 2007 the Buttercup Bake Shop opened, remaining until around 2014. Looking above the 1927 commercial addition, the passerby can see the top floors of Nathaniel Hess’s 1886 residence, a relic from a gentler time on West 72nd Street.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

141 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 141 West 72nd Street:

Meet Allen Ng!

Meet Sarah Berman!

Meet Robert Stern!

Meet Lora Heller!

Meet Sebastian Alappat!