View of 135 West 72nd Street from south. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

Regine Took Herself “to the Cleaners”

by Tom Miller

The handsome, four-story, high-stoop brownstone house at 135 West 72nd Street was designed by architects Thom & Wilson and completed in 1887. At the time, West 72nd Street was lined with sumptuous rowhouses like this one. By the turn of the century, it was home to Robert Bayard Carpenter and his wife, Nellie L. Carpenter.

Nellie died on January 2, 1902. The opulence of the mansion was reflected in the sale advertisement in December that year. It described the house as “exquisitely decorated; beautifully trimmed in hard woods, including elegant gas fixtures, andirons, onyx mantels, shades, etc.”

It became home to the Phineas C. Kingsland family. Born in 1842 Kingsland had served in the Civil War. The Kingslands would not stay long. Phineas sold the house to Rudolph Oelsner in December 1905.

Change would come to West 72nd Street before long. At the end of World War I, commercial traffic, once banned from the street, was moving freely and the lower floors of many houses were being converted for business purposes. On November 14, 1920, the New-York Tribune reported that the one-time Carpenter mansion had been sold to the 135 West Seventy-second Street Corporation.

The newly organized development group hired the architectural firm of Gronenberg & Leuchtag to make massive renovations to the house. Its plans, filed in February 1920, called for a new façade, an additional story, an elevator, and the rearrangement of the interior walls.

The stoop was removed, the front pulled forward to the property line, and a prim brick façade in the “20th century commercial” style was erected. The renovations cost the owners the equivalent of a quarter of a million in today’s dollars—a considerable savings over demolishing the house and starting from scratch.

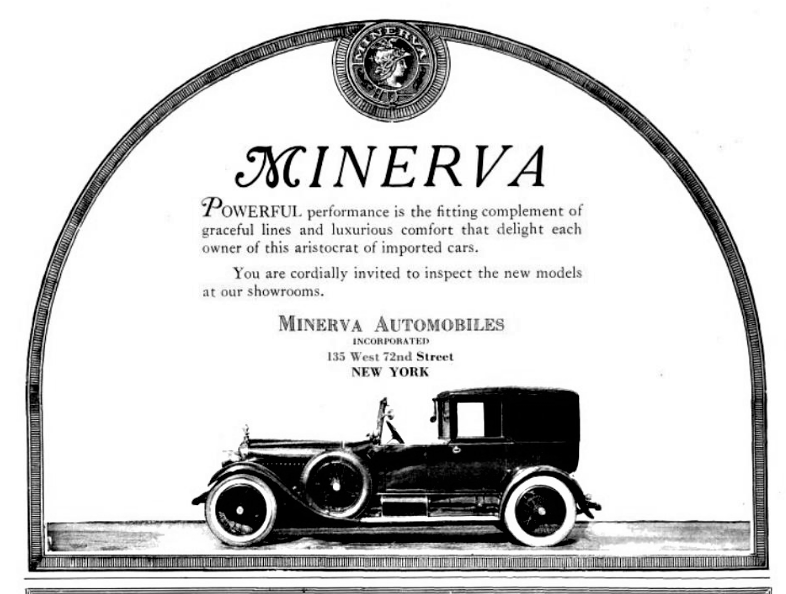

Minerva Automobiles, Inc. opened its showroom here in 1921. The luxury motorcars had been made in Belgium since 1902.

The renovated structure was quintessentially multi-purpose. An advertisement in August 1920 described, a “very desirable street-level store [with] high ceiling, doctor’s and dentist’s suites, photographer’s studio [and] 2 and 3 room apartments with Kitchenette.” Rents for the medical suites and the apartments ranged from $100 to $125—just over $1,800 per month by today’s standards.

Leases were quickly signed. The Real Estate Investors of New York took an office, and one of the medical suites was leased to Dr. Edward P. Fischer. In December 1920 the second-floor space was rented to Elphick & Crabb, “who will conduct a school for golf instruction,” according to the New York Herald. But most impressive was the ground floor tenant.

Minerva Automobiles, Inc. opened its showroom here in 1921. The luxury motorcars had been made in Belgium since 1902. They were, by now, popular among American motion picture stars, industrialists, and politicians.

Among the original apartment residents was Hanna Brocks. In 1921 the Musical Courier reported:

Hanna Brocks, well-known concert soprano and teacher, has recently returned from her summer home where she and several of her pupils enjoyed a very pleasant season, and has opened a new studio at 135 West 72nd street, New York. Mme. Brocks reports many pupils and concerts booked for the season.

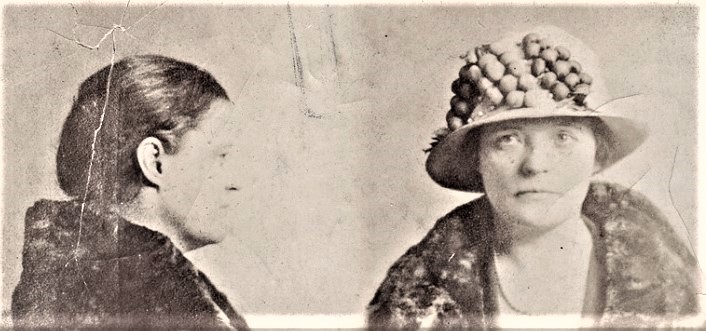

Also living here at the time was 36-year-old Ethel Bruce Attell, the divorced wife of champion fighter Abe Attell, who had been disgraced in the White Sox baseball scandal of 1919 (he was connected with the “throwing” of the game). When police came by her apartment on January 10, 1922, the landlord said he had not seen her since the previous day, “when she removed her trunk from her apartment and fled in a taxi, forgetting, in her haste, to leave a forwarding address.”

Ethel was in a hurry to leave because she was jumping bail before her trial, which was scheduled to begin on January 14. She had been arrested for being the mastermind in “recent spectacular mail robberies, involving losses of more than three million in Government bonds,” according to the Daily News on January 11.

She had been arrested on December 31, 1921 as she attempted to cash a $500 bond in the delicatessen of Jacob Orgel on 49th Street near 7th Avenue. Almost immediately after her arrest detectives rounded up her alleged accomplices, Sam Gold and Harry Cohen, who shared her apartment. The News-Review of Roseburg, Oregon added, “The inspectors said they found a complete opium set in the apartment.”

Ethel was eventually found and, rather unbelievably, she wriggled out of the Liberty Bond theft case and a series of fur thefts for which she had previously been arrested but not yet tried. She ended up not being charged in any of the crimes.

In September 1926 Lawrence L. Elzas leased the former automobile showroom for his Federal Dry Cleaning Company store. His wife, Regine, and infant son were living at the home of his in-laws in Hudson, New York. The couple had been married in September 1925 and things were not going well. On June 1, 1926, the day after their son was born, Lawrence left and moved to New York, coming back only on the weekends.

Regine later said that in June and July, while she was in and out of the hospital, he “would occasionally strike me, would refuse to permit me to nurse the baby, and, on other occasions, in the presence of household servants, would call me by vile names, such as ‘son-of-a-bitch.”

Four hours later police were back. The unnamed man had returned with a friend and shot Hopkins in the head and Dalton in the chest.

Regine made a serious mistake on October 6, 1926, by going to the dry cleaning shop, hoping to convince her husband to give her money for her and the baby to live on. She testified later, “My husband refused to permit me to enter the store, grabbed me by the neck, tore my beads off and scratched me and bruised me considerably, creating a public disturbance, to my great humiliation and pain.”

The not-so-nice dry cleaner was in business only a few more months. In 1927 the space became home to the Lafayette Cafeteria. The second-floor space changed hands that year, as well. It was now the dance studio of Miss Newall, who taught “Ballroom Dancing [and] Tango,”

On the night of August 10, 1933, tenant John Dalton hosted a poker party. Things got out of hand and around 4:15 in the morning police were called about a disturbance. According to The Knickerbocker Press, they “found Dalton and [Noble] Hopkins arguing with a man who had been hit with a bottle. Police sent the man on his way.” Noble Hopkins was the building superintendent. Four hours later police were back. The unnamed man had returned with a friend and shot Hopkins in the head and Dalton in the chest.

At the time of the shooting, the former cafeteria had become Beran’s Restaurant. With the end of Prohibition in December 1933, the restaurant obtained a liquor license in 1934.

A renovation completed in 1945 resulted in a total of ten apartments above the ground floor store. One of those apartments doubled as the headquarters of the Dissenting Democrats in 1967. It was described by a reader of the Schenectady Gazette as “a promising organization to dump [Lyndon B.] Johnson in the coming Democratic convention, and to elect peace candidates for Congress.”

In the 1990’s the ground floor was home to the upscale boutique, Cele. Today a nail salon occupies that space while (although officially still listed as an apartment) the second floor houses a real estate firm. A coat of moss-green paint hides the contrast between the brick and terra cotta ornament, but overall most of Gronenberg & Leuchtag’s 1920 design survives.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

135 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 135 West 72nd Street: