Especially for Doctors, Specialists, Dentists

by Tom Miller

Builder and contractor James J. Slevin’s family had lived in the handsome 22-foot wide residence at 133 West 72nd Street for years by 1911. But the once tranquil residential neighborhood had become increasing commercial and vehicular and foot traffic now shattered the family’s domestic calm.

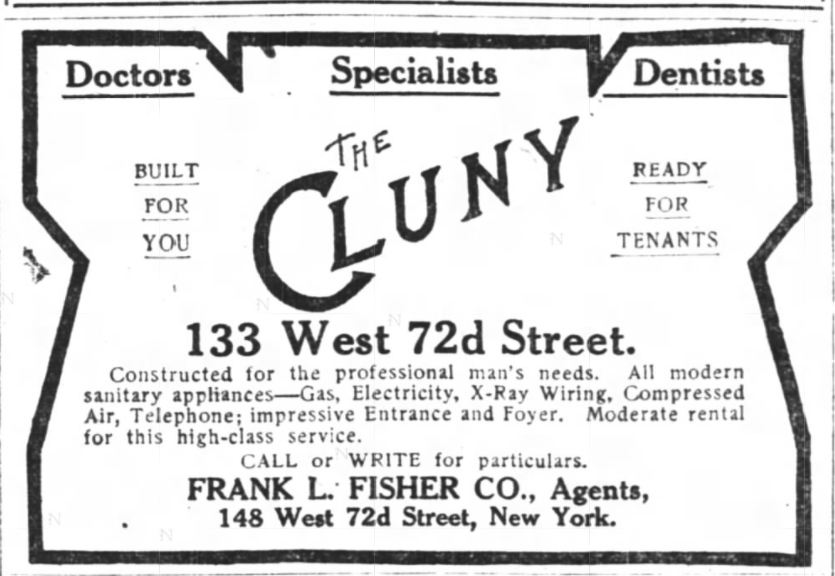

On June 4 that year The New York Times reported “Within a few days another of the fine private residences on Seventy-second Street, between Broadway and Columbus Avenue, will be torn down, adding one more link in the chain that is making this thoroughfare one of the most important cross-town business streets on the west side.” Slevin had sold his house to the newly formed Cluny Realty Corporation. The article continued “on its site will be erected an attractive seven-story apartment building to be used exclusively as offices for dentists and doctors. The latest improvements and conveniences will be provided, particular attention being paid to the lighting features of each office.”

It would be interesting to know if the Cluny Realty Corporation took its name from the plans of architect Charles E. Birge, or if Birge modeled the architectural style of the building after his employer’s name. Either way, The New York Times explained that Birge “has treated the façade in the French Celtic style of the type of the famous Cluny Palace in Paris.”

Other than its height, the resultant limestone-faced structure looked perhaps more like a mansion than an office building. A short, three-step stoop led to the double-doored entrance. The first and second floors were decorated in carved French Renaissance motifs and the tall stone parapet atop the roofline was decorated with pierced Gothic panels. The $75,000 cost of construction would be equal to just over $2 million today.

An advertisement intent on luring physician tenants promised that patients would enter a smart foyer with “caen stone [a soft marble-like material] walls and tiled floor, beautiful settees and chairs of Henry II period (specially made) on either side, with rug in center, white pedestal, covered with plants and ivy,” said an advertisement. “CLUNY lace curtains hang on doors and windows, plants in window boxes outside, elevator boy in livery, maid in constant attendance—everything the best; highest class service furnished.”

“Within a few days another of the fine private residences on Seventy-second Street, between Broadway and Columbus Avenue, will be torn down, adding one more link in the chain that is making this thoroughfare one of the most important cross-town business streets on the west side.”

Each of the offices had four rooms (operating, laboratory, reception and “retiring”, a toilet and two washrooms. They were fitted for “gas, compressed air, X-Ray wiring, [and] telephone connections,” according to one advertisement. The operating rooms were equipped for minor operations. Perhaps to prevent unwanted stains, the floors were “ox-blood tiled.”

The Cluny Building filled with physicians and dentists. One of them, Dr. Bruno W. Kirschner, seemed to have everything in 1914—a successful career, a fine home on West 135th Street, and a wife and daughter. But soon after the birth of their second child in the fall of that year, Kate Kirschner became despondent with what today would be termed postpartum depression. In October Dr. Kirschner had her admitted to the Jacobi Sanatorium in New Rochelle for treatment. Tragically, on February 25, 1915 Kate eluded her nurse by climbing out a bathroom window, dropping to the porch roof and then to the ground. Wearing only a bathrobe and nightgown, she found a stream on the property where she drowned herself.

One-year old Dorothy Charlotte Kirschner was temporarily placed in the care of her aunt, Charlotte Gustow, in Queens. When Dr. Kirschner remarried shockingly soon after his wife’s death, Mrs. Gustow had one more reason not to want to return the child to him. When she steadfastly refused to turn Dorothy over to him, Kirschner took her to court where she laid out her litany of charges.

On November 18, 1816 the New-York Tribune reported that Charlotte told the judge the dentist and his new wife “go out to restaurants and to the theatre almost every evening” and “She was also perturbed about the religious training of the infant, Dr. Kirschner being a Jew, while Dorothy was christened in a Methodist church. Mrs. Gustow expressed the fear that Dr. Kirschner might not permit his daughter to attend Sunday School.”

Judge John P. Colahan (who had seven children of his own) was not moved. “A father has the right to go to the theater and restaurants every night and still bring up his family. One hundred thousand families in this city are living just this way.” And as for the religious argument, he said “No one has a better right to select the creed in which a child shall be brought up than the parent. Be he Catholic, Protestant, Jew or Atheist, we cannot deprive a father of his child because of his religious beliefs.” Dr. Kirschner regained full custody of his daughter.

A bizarre incident surrounded Dr. Harold E. Roy in 1921. Dr. Roy, the son of Dr. F. Austin Roy, was 31-years old and lived with his wife on West 83rd Street. The skinny dentist was described by the New York Herald as “unusually tall, being 6 feet 3-1/2 inches” but only 165 pounds.

On the afternoon of Thursday, March 17 he took a canoe from the Interstate Boat Club at the foot of Dyckman Street and started paddling across the Hudson River. And that was the last anyone heard of him. The New York Herald reported two days later, “The water was rough, and members of the club recall having seen an oil tanker passing up the river in midstream pause and turn about several times about the time Dr. Roy would have been well out toward the Jersey side.” On Friday afternoon, a canoe with a battered prow drifted near the Columbia Yacht Club at 86th Street. “It was half filled with water,” said the newspaper.

Three months after his disappearance the life insurance company issued a check to Gladys C. Roy for $10,000. But nearly a year later, in February 1922, the Bankers’ Life Company was looking for Gladys and wanted its money back. A man was discovered in the West, “who is said to follow closely the description of the dentist,” reported the New York Herald. The article added that he “is believed to be suffering from amnesia and has scars about his head which indicated he has been in an accident which robbed him of his memory.” The insurance firm quickly devised its explanation. “Dr. Roy was in collision with a boat about midstream. It is believed the person or persons in the craft that hit the canoe picked up the dentist’s body, found he had been seriously injured and, in an effort to ‘cover up,’ carried him up into Canada, probably by water, and dumped him off somewhere along the St. Lawrence River.” (The man had been found with Canadian money in his pockets.)

The New York Herald added “A peculiar part of the case is that friends of Dr. Roy have seen the man in the West and have not been able to make an identification. They say that the resemblance is remarkable, but there is something about the man which makes them hesitate to make a positive identification.” Hesitation aside, the mystery man was identified as the missing Dr. Roy by the beginning of March 1922 and Gladys had to repay the death benefits.

Just after mid-century the Cluny Building was seeing the first tenants not affiliated with the medical profession. In 1959, for instance, the De Lys Theatre Associates, Inc. had its offices in the building. A renovation completed in 1965 replaced the domestic-looking first floor with a modern storefront. Thankfully, Charles E. Birge’s French Renaissance decorations were preserved.

“Dr. Roy was in collision with a boat about midstream. It is believed the person or persons in the craft that hit the canoe picked up the dentist’s body, found he had been seriously injured and, in an effort to ‘cover up,’ carried him up into Canada, probably by water, and dumped him off somewhere along the St. Lawrence River.”

The days of doctors and dentists had come to an end. In 1967 the headquarters of the newly formed Jeanette Rankin Brigade opened in the building. It the group was dedicated to peace and ‘to bring the (American) boys back from Vietnam,” according to its 87-year old founder and namesake. It was possibly in association with the Jeanette Rankin Brigade that The Viet Report was published here. According to the 1969 minutes of the Congress’s Committee on Government Operations, “The Viet Report is a monthly publication critical of U.S. policy in Vietnam…Viet Report sales are primarily confined to college campuses.”

Less controversial were tenants like the Soulmate, an apartment sharing and roommate referral service for single women. The agency “places emphasis on the special housing needs of Black women,” explained the N.Y. Amsterdam News on February 6, 1971.

Around 1974 the New York Hair Center opened in the building. It marketed “The Ultra Skin Hair Replacement” and promised bald or balding men that their new hair would be “totally undetectable. Sleep in it, shower, or swim. It won’t come off.” By 1977 Bazaar salon was leasing space. The parlor not only styled hair but had a hot line for advice on hair that was “too curly, too straight [or] been messed up by a poor permanent of coloring.”

In the spring of 1983, Club de Beauté operated within the building. The spa offered a variety of methods to lose weight, promising that a client could lose unwanted inches in 90 minutes. Included in the procedures were steam cabinet sessions, “pressotherapy,” cellulite massage and “passive muscle exercise.”

Other than the renovated ground floor, the Cluny Building is little changed after more than a century.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

133 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 133 West 72nd Street:

Meet Tracy Hattem!

Meet Rebecca Correia!

Meet Satu Ferentz!