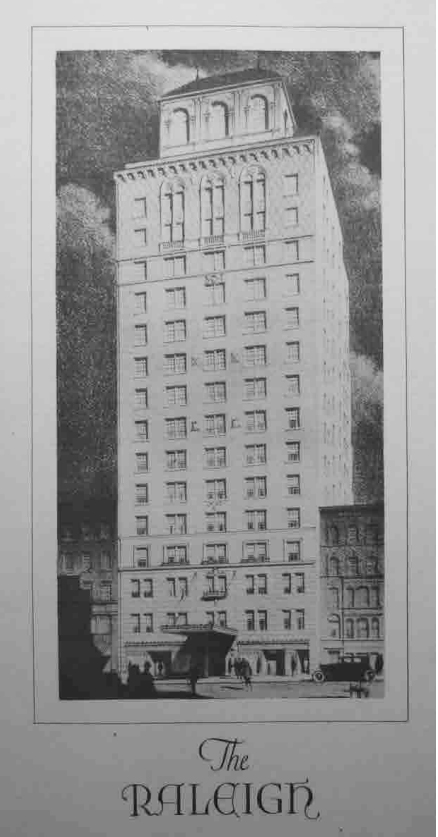

View of Raleigh Apartment Hotel at 121 West 72nd Street from south. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The Hotel Raleigh

by Tom Miller

In 1925 Nathan Minskoff, who headed the Milnat Realty Corp., demolished the three 1887 rowhouses at 119 through 123 West 72nd Street. He hired Hyman Isaac Feldman to design a residential hotel on the site. Feldman, who was 32 years old and went professionally by his initials, had started his practice just eight years earlier. He would soon become well-known for his Art Deco apartment houses along the Grand Concourse in the Bronx and similar buildings in Brooklyn.

But for the Hotel Raleigh Feldman turned to the Italian Renaissance for inspiration. His 15-story tripartite design featured a three-story rusticated stone base. Retail store spaces flanked the centered, arched entrance. The mid-section was relatively unadorned, Feldman making use of light and dark brick to provide visual interest. Lavish decoration was reserved for the top two floors where double-height terra-cotta framed arches created the illusion of balconies and a terra cotta cornice rested up an elaborate corbel table.

Hotel Raleigh was a residential hotel–essentially an apartment house with amenities of an upscale hotel, like maid and linen service. The suites of one, two or three rooms had no kitchens, prompting the Department of Buildings to note, “no cooking is permitted in any apartment of this building.” Residents enjoyed amenities like the rooftop sun parlor, solarium and children’s playroom.

Although the apartments were somewhat small, they filled with professionals, like Dr. Morton K. Hertz, an initial resident. A bachelor, the young physician treated some recognized personalities, like Mildred Richardson Hill, a former chorus girl whom Florenz Ziegfeld described as “a perfect American beauty on a perfect stem.”

Residents enjoyed amenities like the rooftop sun parlor, solarium and children’s playroom.

Dr. Hertz became unintentionally involved in her divorce from millionaire rancher Walter J. Hill in 1927. The Daily News reported on October 20, “According to Mrs. Hill in a telegram yesterday to her friend and personal physician, Dr. Morton K. Hertz of 121 West 72d st., Hill changed his manners from those of a cattleman to those of a boulevardier when he came east, but on returning to Montana with his bride reverted to type.” The Daily News surmised, “Walter turned out to be wilder and woolier than she had fancied, it appears.”

Dr. Hill’s name appeared in the newspapers again the following year when he treated executioner Robert Elliott for a nervous condition. The Evening Post described Elliott as “that strange, cadaverous craftsman who holds a monopoly on executions in five States,” and said, “Never before has this gimlet-eyed man who plays with wires that send his fellows to eternity been shaken.” But the double execution he performed on January 12, 1928 was different.

Ruth Snyder and her lover Judd Gray had been convicted of the brutal murder of Snyder’s husband. Both were executed by Elliott, one after the other. But the thought of executing a woman totally unnerved him. The Evening Post said he suffered “an attack of ‘nerves’ so severe that it demanded the presence of his personal physician, Dr. Morton Hertz of 121 West Seventy-second Street.” Hertz explained to the press, “the idea of executing a woman—his first—had preyed on his mind.” The newspaper said, “The doctor found his patient ‘pretty badly shaken’ after his task was done.”

Dr. Hertz’s bachelorhood came to an end on January 21, 1931 when he married Selma Y. Rosenthal in the Crystal Room of the Ritz-Carlton. In reporting on the event, The New York Sun noted, “Dr. Hertz is on the staff of the Post Graduate Hospital and a member of the surgical staff of the Broad Street Hospital.”

During the Depression years, one of the commercial spaces was home to the Cecil Restaurant. Following the breakfast rush on February 9, 1934, manager Sam Rosenbloom collected the $300 receipts from the previous evening to deposit. A shivering man walked in and asked for a cup of coffee. Rosenbloom explained that the breakfast was over, and lunch was not ready yet, but he would give the man a dime to buy coffee elsewhere. As he turned to open the cash drawer, the man grabbed the $300 and disappeared into the crowd outside.

Following the end of World War II in 1945, Alfred Gloch obtained a civilian job with the American Military Government in Occupied Germany. When he took advantage of his situation by ignoring regulations against trading with the enemy, he was arrested and jailed in Berlin. The 25-year-old was charged with having “sold liquor, tobacco and other products to Germans at lucrative prices and used the proceeds for purchasing an automobile, a boat and other items and renting a large house from Germans.” Gloch was awaiting military court martial in August 1946. The severity of the crime was such that another man involved in the scheme had committed suicide while under investigation.

In 1949 the building was converted to a true apartment house, with no more than seven apartments per floor. The former Cecil Restaurant space was leased to brothers Jack and Charles Strauss in the summer of 1956 for their Polka Dot restaurant-cabaret. Writing in his Broadway Showcase column on August 3 syndicated columnist Paul E. Pepe wrote, “The Polka Dot Restaurant is a combination restaurant-supper-club-nitespot that is fast becoming one of the high spots in Gotham nightlife.” He went on, “the Polka Dot, now becoming better known as a supper-club and after-theatre spot also boasts a top-rate floor show.”

Starting around 1959 the Hotel Raleigh was home to several Soviet diplomats. That was still the cast in 1962 when Nicolai Vasilevich Russkikh and Alexander F. Baryshev, Second and Third Secretaries, respectively, to the USSR Consulate lived here.

The 25-year-old was charged with having “sold liquor, tobacco and other products to Germans at lucrative prices and used the proceeds for purchasing an automobile, a boat and other items and renting a large house from Germans.”

A colorful resident at the time was Dr. Harry L. Kenmore. He became intensely interested in Indian spiritualism and in 1959 flew to India to meet the yoga guru Meher Baba. Baba claimed to be the Avatar, or God in human form. The trip was not cheap—Kenmore’s round-trip ticket costing the equivalent of more than $17,000 today.

In 1967 Dr. Kenmore opened The Society for Avatar Meher Baba in the second-floor apartment next door to his. Kenmore spoke about the yoga guru during the weekly Saturday night meetings. That year, according to compilers Larry and Rita Karrasch in their 2017 book Harry, The Story of Dr. Harry L. Kenmore and His Life with His Beloved Pop, Meher Baba, “Baba gave Harry an order to hold two Public Celebrations each year; Baba’s Birthday and His Silence Day Anniversary.”

In 1971 the Polka Dot space was renovated for Jennifer House furniture and interior decorating store. The other space became home to Edward Walsh Flowers.

Among the residents in the 1970’s was Broadway actress Barbara Coggin. She was in the original 1976 production of Poor Murderer along with Kevin McCarthy, Laurence Luckinbill, Maria Schell and Ruth Ford. In 1979, she took the role of Bunny Weinberger, originated three years earlier by Jessica James, in the play Gemini. She was still performing in that play when, on January 19, 1981, she died in her sleep. The New York Times reported, “A medical report said that the actress had died of natural causes.” She was 41 years old.

The Jennifer House space was later the long-time home to Long’s Bedding, a mattress and bedding store, and now the former Edward Walsh’s florist shop is a UPS store. Other than unsightly window air conditioners, little has changed in the Hotel Raleigh since it opened in 1926.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

121 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 121 West 72nd Street: