Harsen House

by Tom Miller

On December 20, 1890, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide opined, “Seventy-second street is probably the best street on the West Side…on a fine afternoon it rivals 5th avenue in the elegance of the numerous equipages which pass through the street.” The article noted that the West 72nd Street was lined “with the highest class of private residences,” and said, “Among these, the latest, the most expensive and therefore, presumably, the best, are the eight four-story dwellings built by Mr. Francis Crawford.”

Each of the brownstone-fronted homes were 25-feet-wide and four stories high above high stone stoops. Inside were inlaid oak floors, and white mahogany woodwork. The dining rooms had built-in buffets and full-length pier mirrors. On the second floor were the library and the master bedroom, and in the hallway an ingenious series of buttons which, when pushed, ignited an electric spark that would turn on the gas lamps in the room selected. Another innovation was a burglar alarm system connected to every door and window in the basement through second floors. Should a window or door be opened, an 8-inch gong on the outside of the house would ring. The Record & Guide pointed out, “The same instrument may be set to any hour in the morning to awake the servants, whose rooms are on the fourth-floor, at the same time turning off the burglar alarm.”

The article added, “On the basement floor there is a billiard and smoking-room, 17×26 feet in size, handsomely finished in carved hardwoods, with a mantel, in which are set several mirrors.” Also in the basement were the laundry, kitchen and a coat and washroom.

In June 1891 Crawford sold 120 West 72nd Street to the Rev. Philip Auld Harrison Brown and his wife, the former Jane Russell Averell Carter. Born in Baltimore in 1842, Brown had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War, seeing action in the battles of Cedar Mountain, Cold Harbor and Gettysburg. He completed his religious training in 1871 and became vicar of Trinity Parish in 1875.

Should a window or door be opened, an 8-inch gong on the outside of the house would ring.

Philip and Jane had eight children. Their country home, Holt Averell, was in Cooperstown, New York, where Jane had been born. Jane had inherited it upon her mother’s death in 1888.

In the meantime, Crawford sold 122 West 72nd Street to Charles G. Emery on October 13, 1891 for $75,000—the equivalent of $2.2 million in today’s money. Emery made a substantial profit two years later when he sold it to Daniel Appleton for $80,000.

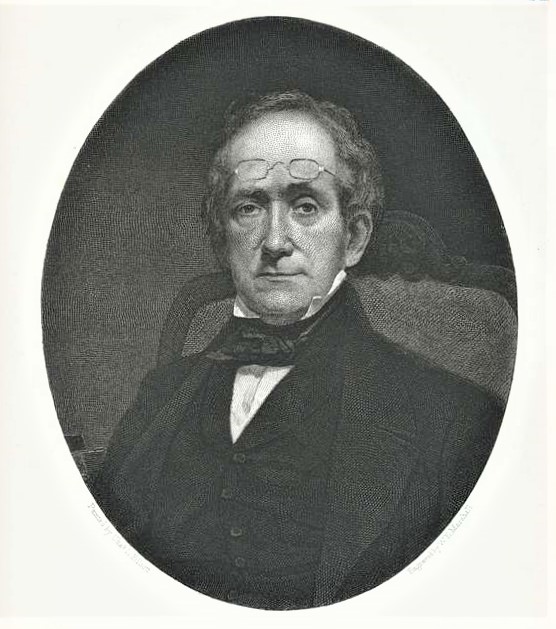

Appleton’s family had arrived in America early in the 17th century. His grandfather had founded the publishing house of D. Appleton & Co. in 1838. Daniel was born in 1852 and, after studying in Germany, entered Harvard College. By the time he purchased the 72nd Street house he had been a partner in D. Appleton & Co. for 12 years.

Daniel Appleton was a bachelor and his widowed mother, Serena P. Dale Appleton, moved into the house with him. Their country home, Rockhurst, was in New Rochelle, New York.

The year 1900 was socially important to the Brown family. On January 14, The New York Times reported, “On Monday last, Mrs. Philip Brown of 120 West Seventy-second Street gave her daughter Jean, a debutante of this season, a luncheon, to which some twenty young women were invited.” The prominence of the family was reflected in the names of the guests, De Peyster, Schuyler, and Delafield among them.

Serena Appleton died on the evening of January 8, 1902. The New-York Tribune attributed her death to “the infirmities of age.” She was 76 years old. Soon thereafter, Daniel Appleton moved to 436 Fifth Avenue, and leased 122 West 72nd Street to Edwin Fowler and his wife. Fowler converted the mansion to the Columbia Institute, a boys’ preparatory school. It offered courses “from primary to college,” including “optional Military Drill.”

Rev. Philip Auld Harrison Brown died on September 15, 1909. While Jane retained possession of the house, the family almost immediately moved out. It was leased to Mrs. Mary Philips, who operated it as a high-end boarding house.

Following the end of World War I, West 72nd Street was seeing noticeable change, as former mansions were being converted for business, or being replaced by modern apartment buildings. In October 1919, Daniel Appleton and Jane R. A. Brown simultaneously sold their properties to Samuel Wheeler. The architectural firm of Ross & McNeil, in association with George A. Wotherspoon, converted the houses. The stoops were removed, and storefronts installed. The upper floors were combined internally to become a bachelor apartment house.

Davis paced about, presumably waiting for his friend to re-emerge. He then casually slipped a gold mesh bag, valued at $150, into his pocket.

The ground floor became home to the Aristocrat Restaurant. Upstairs, not every tenant was especially upstanding. On the afternoon of January 17, 1921, a tenant, William Davis, entered the J. M. Gidding & Co. department store with a woman. The New York Times said, “The man was tall and stylishly dressed; his companion was swathed in furs.” The woman asked to be shown to the ladies’ room and she and Davis were taken to the fourth floor. Davis paced about, presumably waiting for his friend to re-emerge. He then casually slipped a gold mesh bag, valued at $150, into his pocket.

A salesgirl saw the theft and screamed “Stop, thief!” The store detective chased Davis onto 47th Street and towards Sixth Avenue. When Davis refused to halt, the detective shot his revolver. The New York Times said, “The bullet passed under the man’s left ear and grazed his cheek.” It was enough incentive for Davis to stop. He was arrested, convicted, and sent to the State Penitentiary.

On the night of January 4, 1922, Harry Ritz noticed Ruth Knight, another tenant, walking on Broadway in the rain. He pulled his car over and asked her if she would like a ride home. When they got to the 72nd Street address, she invited him up.

As they entered, they met a man in the hallway, George Phillips, an old friend of Ruth, so she invited him to join them. After having a drink, “it was suggested a game of craps might enliven the party,” reported the New York-Tribune. Conveniently, Phillips had a pair of dice in his pocket. Within 20 minutes Ruth and Phillips “had eighty of [Ritz’s] dollars and a great deal of his enmity.” Not letting on that he suspected loaded dice, he bid them good night then went directly to the West 68th Street police station. The pair was locked up, charged with grand larceny.

In 1937 the combined houses with their checkered pasts were razed, to be replaced with an Art Moderne style “taxpayer”—a single story structure that earned enough rental income to pay the property taxes. It was succeeded in 2008 by a modern apartment building.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

120-122 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 120 West 72nd Street: