Uncovering Cover-Ups at The Oliver Cromwell

by Tom Miller

West 72nd Street was lined with lavish private homes in the 1890’s. But by the 1920’s many of them were being replaced by shops and modern apartment buildings. In 1926 a development firm, Washington Square, Inc., purchase the four rowhouses at 12 through 18 West 72nd Street and hired the prolific architect Emery Roth to design a replacement “apartment hotel.”

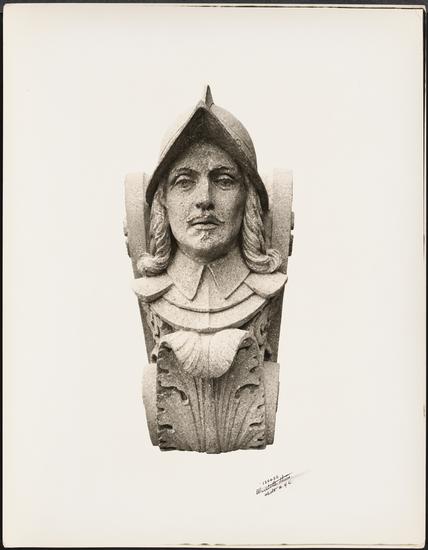

The 29-story building was completed in 1927. Roth had splashed the façade with Italian Renaissance style decorations—pseudo balconies, for instance, which might have sprung from Romeo and Juliet. The deep set-back above the 14th floor provided large outdoor spaces while not only increasing light and ventilation to the upper floors but breaking up the visual monotony of the design.

Called the Oliver Cromwell, its 200 apartments housed a blend of well-to-do transient and permanent residents (hence, “apartment hotel”). On October 31, 1927, for instance, The Troy Times reported in its society column that Colonel and Mrs. Herman Clark had leased the Butler residence in Troy, New York, adding “Mr. and Mrs. H. H. Butler and family will spend the winter at the Oliver Cromwell Hotel in New York.”

At the time of the Oliver Cromwell’s completion New Yorkers (and Americans in general) were merrily and recklessly playing the Stock Market. Everyone from millionaires to taxi drivers invested and it seemed that no one could lose. Among the initial permanent residents of the Oliver Cromwell was stockbroker Arthur Carter, who was reaping enormous profits from it all.

But on August 15, 1929 the Daily News reported that he had been investigated by Assistant United States Attorney George J. Mitzer for running a “phony stock house” which the newspaper deemed a “financial speakeasy.” The article said, “the government charges [he] made millions in Wall Street through manipulation of sucker lists and questionable stock deals.” Carter’s well-heeled neighbors were no doubt shocked when he was led out of the building in handcuffs, charged with “using the mail to defraud and with manipulations of fake stock.”

Another of the first residents was the affluent bachelor Dr. Michael P. Rich whose 26th floor apartment had magnificent views. Born in San Francisco in 1867, he had graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, but, according to The New York Times, “never practiced his profession, as he was independently wealthy.”

He was found unconscious by a runner who summoned a policeman. Detectives found a bloody shoemaker’s awl nearby and a large blood-covered rock. Klein regained consciousness in the Metropolitan Hospital long enough to say he “had been set upon by two colored footpads who had robbed him of several dollars,” as reported by the Daily News.

Gertrude Eisel was a maid in the apartment of Arthur Siegmund six floors below Rich’s. Shortly after 9:00 on the morning of April 12, 1929 she found the body of Michael P. Rich, fully clothed, on the terrace. The New York Times reported “the police concluded that he had jumped or fallen from an open window in his apartment on the twenty-sixth floor.” He had died instantly upon impact several hours before Gertrude noticed his body.

Suicide at the time was scandalous and wealthy families went to great efforts to dispel rumors whether they were true or not. Four days later The Brooklyn Daily Eagle was not even entertaining the possibility that the 62-year old had committed suicide, saying he “died accidentally in a six-story fall from his apartment in the Oliver Cromwell Hotel.” He left an estate of about $6.5 million in today’s dollars, about one-fourth of which he left to charities.

The Great Depression had little effect on many of New York’s wealthy families, like those who lived in the Oliver Cromwell. Among the residents in the 1930’s were retired diamond dealer, David de Sola Mendes and his wife, Leah; Max V. Miller, president of the Madison Square press, and his wife, Elizabeth Lovett Miller; and accounting firm executive Charles A. Klein.

Born in Cleveland, Klein was the principal in Charles A. Klein & Co. on Fifth Avenue. The 60-year old was walking through Central Park around 8:00pm on the night of December 2, 1937 when, according to The Sun, he was “set upon by thugs.” The muggers “stabbed him, bludgeoned him with a heavy rock and left him to die.”

He was found unconscious by a runner who summoned a policeman. Detectives found a bloody shoemaker’s awl nearby and a large blood-covered rock. Klein regained consciousness in the Metropolitan Hospital long enough to say he “had been set upon by two colored footpads who had robbed him of several dollars,” as reported by the Daily News. His attackers “sprang at him suddenly, one throwing an arm around his throat before he could escape. As he struggled to free himself one of them stabbed him four times in the chest, twice on each side, and hit him over the head with the rock.” Klein, who suffered a fractured skull, head wounds, a broken neck and stabs wounds, died at around 4:00 in the morning.

As 4,000 policemen were detailed to find Klein’s murderers, an unbelievable twist in the case developed. On December 6, 1937 the Daily News reported “Police last night believed that Charles A. Klein…might have committed suicide.” Two young men, 21-year-old Charles Tobin and 20-year old Edward Gerke, had gone to the offices of the Daily News saying “We saw a fellow about 60 years old hitting himself on the head with a rock. We didn’t pay much attention because we thought he just might be nuts. At about 7:35 we passed the same place on our way back, and we saw a man lying on the sidewalk with a young fellow bending over him, trying to help him. We told a cop at 59th Street about it, but he thought it was a gag, so we shut up.”

Astoundingly, the Daily News continued, “Police now theorize that Klein attempted to stab himself to death with an awl, then struck himself with the rock…They were inclined to ignore Klein’s own story.” Modern forensics and medical knowledge would be less willing to believe he could have successfully fractured his own skull, broken his neck and stabbed himself.

The circumstances surrounding the death of another Oliver Cromwell resident the following year were almost equally bizarre. Artist Irene Racz shared an apartment with her mother, Catherine. Irene, who was 30-years old, was born in Budapest and was a successful painter. They had come to New York in 1930. Four years later Irene held her first one-man show in the Piggins Galleries in the Hotel Roosevelt. Her works were repeatedly exhibited in similar shows in well-known galleries over the next years. After settling in New York, she had turned to “the American,” according to The New York Times, “particularly the metropolitan scene.”

Despite her artistic success, Irene was suffering from mental problems. On the morning of August 22, 1938, Catherine found her dead in bed. A note in Hungarian read:

Dearest Mother: I am going to commit suicide and I want you to do give the dog some of the poison and take the rest yourself. I will meet you in the next world. Don’t call any one or let any one in the apartment until you have done this.

Their apartment had been entered and Mrs. Feinstein’s jewelry stolen. It was the fifth such burglary within five days. Included in the heist was a 25-carat diamond ring valued at $253,000 in today’s money. The Daily News reported it “had been kept in a manila envelope secreted in a bedroom closet. The closet was locked, but the thieves opened it with a celluloid strip.”

Sally Miller lived here in the 1950’s. The estranged wife of Jules Miller, described by the Daily News as a “wealthy cloak and suiter,” she was remembered by many New Yorkers as a former musical comedy singer.

On the evening of March 20, 1955, she had her sister, Mrs. Jeanette Fisher, over. At around 7:00 Morty Karp, a tile contractor, joined them. Sally knew him because his brother lived in the building. He asked if he could wait there until his brother came home.

At some point conversation turned to jewelry and Sally showed her guests an 8.4-carat diamond ring her husband had given her (the $10,000 valuation would be closer to $95,500 today). She then put it back in the dresser drawer in her bedroom. On October 17 the Daily News reported, “Later, she related, Karp made two or three trips to the bedroom to make phone calls. When she went to the dresser to get the ring, she found it gone. Karp and her sister were still in the apartment, she said.”

Sally immediately called the police and the insurance company, “but Karp left before the cops arrived,” said the article. Although suspicion landed squarely on Karp, the ring was never recovered. The Home Insurance Co. refused to honor its coverage, saying that Sally had failed to “safeguard and secure” the ring. And so, Sally Miller sued.

Sally Miller’s expensive jewelry was no exception among the residents of the Oliver Cromwell, a fact that was typified by William Feinstein, the owner of a chain of ladies’ dress shops, and his wife. The couple lived here in 1962 when a rash of hotel burglaries took place.

At around 2:00 on the afternoon of December 2, they left their apartment, returning six hours later. Their apartment had been entered and Mrs. Feinstein’s jewelry stolen. It was the fifth such burglary within five days. Included in the heist was a 25-carat diamond ring valued at $253,000 in today’s money. The Daily News reported it “had been kept in a manila envelope secreted in a bedroom closet. The closet was locked, but the thieves opened it with a celluloid strip.”

Other residents at the time were Dr. Herbert Block and his wife, Ruth Miller Block. A psychiatrist with Grasslands Hospital in Eastview, New York, he was also part of the medical department of Macy’s.

Samuel L. Deitsch was a founder of the Fashion Institute of Technology and a founding partner of Dietsch, Wersba & Coppola, Inc., women’s apparel manufacturers. He and his wife, Frances, maintained a country home in Danbury, Connecticut where, according to The New York Times, they had “an outstanding collection of early American furniture.”

In 1970 science fiction author Isaac Asimov moved into the Oliver Cromwell, staying through 1973. But perhaps an even more celebrated tenant was actress Sigourney Weaver and her husband, stage director Jim Simpson. They moved in shortly after their marriage in 1984.

A retail space had operated from sidewalk level since 1950. It was home to Sidewalkers’ restaurant in the mid 1980’s, described by the Daily News on September 26, 1986 as not “just a restaurant: It’s a festive dining experience.” The article advised, “Leave your Emily Post dining manners outside before you enter this crowded, noisy, casual and fun dining place.”

The affluent tenants of the Oliver Cromwell coexisted with the “crowded, noisy” restaurant until its closure in 1994. But they were less willing to accept its replacement, a food market. The New York Times called it, “Not just any market, either, but a new breed: a gourmet retail food market with a restaurant that features its own wares.” It posed a problem for the tenants, however. “But to the residents of the Oliver Cromwell, the whole thing boils down to one thing: takeout,” said The New York Times.

One resident explained “We have no objection to a different restaurant, but we are very vehemently opposed to having a take-away market. It would draw everyone from Central Park to our block, impair the character of our block, and make it more commercial.” A compromise was reached with restaurant owner Danny Evans, who also owned the Gourmet Garage in Soho, and the new shop opened in June 1995.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

12-18 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Meet Sammy Radoncic!