View of 116 West 72nd Street from north. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archive LINK

The George Washington (Sussex) Hotel

by Tom Miller

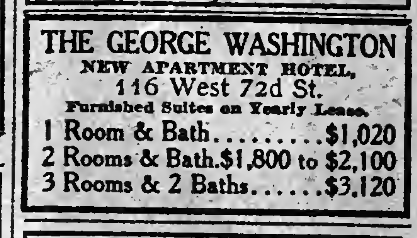

On January 26, 1917, The Sun announced that W. H. Waitt had purchased the two high-stooped houses at 114 and 116 West 72nd Street from Charles A. Dards and Mary E. Jones. The article explained that Waitt, who was the principal in the Waitt Construction Company, “will erect a fifteen story hotel from plans by Schwartz & Gross.” The architects placed the construction costs at $500,000—more than $10 million in today’s money.

Completed the following year, the Italian Renaissance inspired George Washington Hotel had a restaurant on the ground floor, and apartments ranging from 1 room-and-bath to 3-rooms-and-2-baths in the upper floors. Yearly leases for the largest apartments were about the equivalent of $3,900 per month by today’s standards.

Among the tenants in 1919 was Jeanne Loraine. She had been engaged to a soldier, Bernard Goldsmith, since 1917, just before he left to fight in France. The first of Jeanne’s problem came on February 7, 1919, when, according to her, a man she knew as Eddie Hart and Detective Ferdinand J. Chapey had “forced an entrance to her apartment and relieved her of some money.” She complained to Police Headquarters and an investigation was launched.

The Sun reported on June 1, that “Chapey said at the time that he was making an investigation in a homicide case for the District Attorney’s office.” Jeanne’s complaint was dismissed, but shortly afterward, Chapey was demoted to patrolman. After having been on the force 10 years, he resigned.

Suffering from shell shock (known today as post-traumatic disorder), Goldsmith arrived in New York in July and informed Jeanne that he no longer wanted to be married.

Jeanne Loraine’s name was back in the newspapers two months later. Her fiancé had returned from the war a changed man. The Sun reported on August 6, 1919, “Six months in a section of rainy France not conducive to longevity, sightseeing or romance because of the proximity of German troops, artillery, airplanes and snipers gave Bernard Goldsmith, 26, who now lives at the Hotel Belleclaire, lots of time for reflection.”

Suffering from shell shock (known today as post-traumatic disorder), Goldsmith arrived in New York in July and informed Jeanne that he no longer wanted to be married. “When he returned,” said The Sun, “there was a stormy interview during which Goldsmith said his experience in France had caused him to change his mind and he emphatically stated he had no intention of getting married at the present.”

Jeanne Loraine responded with a quarter-million-dollar lawsuit for breach of promise. When told of the suit, Goldsmith’s father, a lace manufacturer, exclaimed, “Why this is a joke. My boy can’t be sued for $250,000. He hasn’t got his civilian clothes all paid for yet.” In the end, the marriage never took place and Jeanne Loraine did not get the $250,000 needed to mend her broken heart.

Other residents at the time Mary Watson, the mother of well-known actress Irene Fenwick; and R. Daniel Wolterbeek and his wife, Grace. Born in Holland in 1860, Wolterbeek was in the import-export business on Frankfort Street. He left on a business trip to Europe in the spring of 1920, expecting to return on July 1. He would not make that voyage. On May 27 Grace Wolterbeek received a telegram informing her that he had died in Germany. His body was transported to Holland for burial.

Despite the small size of the apartments in the George Washington, at least some of the residents were well-to-do. On the morning of November 18, 1921, for instance, A. M. Carlisle and his wife hailed a taxicab at West 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue. The driver waited as they went into the bank in the Hotel Ansonia, then, took them to 282 Madison Avenue. In their hurry, they left belongings in the cab.

The New-York Tribune reported that the cabbie, Thomas Byrnes “discovered two packages…in the tonneau [i.e., backseat] of his machine.” Inside were two mesh bags containing $5,000 in jewelry. He drove to the bank, and then to the Madison Avenue address, but no one could identify the owners. Happily, a policeman somehow tracked down Mrs. Carlisle who went to the police station and identified her jewelry.

Not all the residents of the George Washington Hotel were upstanding. Living here in the spring of 1926 was Joseph Stern, a known gangster. He had taken an apartment here after his former roommate, David Braun, “a gangster and dope peddler,” according to the New York Evening Post, was brutally murdered on September 25, 1925. His body “was found bound and shot in a burning coupe in First Avenue,” said the newspaper.

Detectives Horan and Maloney had been looking for Stern since the incident. They spotted him outside the George Washington Hotel on April 16. “He sprinted toward Broadway and they pursued, pistols in hand,” said the New York Evening Post. “They overtook him and subdued him without firing a shot.” Their efforts were fruitless, however. At the station house Stern insisted he knew nothing about the murder nor about the fur robberies with which he had been connected.

the ring “supplied bogus visas at prices ranging from $250 to $12,000” and “did a business of $500,000 a year.”

In 1929, the George Washington became the Sussex Hotel, a transient hotel. Rates for a single room and bath ranged from $2.50 to $4.00 per night (about $60.50 for the most expensive accommodations)

The Sussex was renovated to apartments in 1950. There were now two stores at sidewalk level, a “club room” and the lobby on the first floor, and four apartments each on the upper floors.

One of those apartments was home to Arturo Arrocho Lopez in 1956. The 45-year-old was arrested in April that year, charged with being the leader of a ring that supplied fake passports to Latin American criminals. United States Attorney Paul Williams told reporters that the ring “supplied bogus visas at prices ranging from $250 to $12,000” and “did a business of $500,000 a year.” Lopez and his cronies had operated the ring since 1953.

A subsequent renovation completed in 1967 increased the number of apartments per floor to five.

In the mid-1970’s one of the stores was home to Japan Art. The crafts shop offered supplies like the Your Own Post Card kit, which allowed the buyer to create his own postcards. The following decade saw The Hernia Center occupying one of the commercial spaces. Today, other than replacement windows, the structure is little changed on the exterior since the 1950 makeover.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

116 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 116 West 72nd Street: