New York’s Most Accessible Hotel

by Tom Miller

On January 6, 1903 Walter Stabler delivered an address to the Real Estate Class of the Y.M.C.A. on “The Development of the West Side.” In it, he outlined the rather stumbling progress of developers in what was, in the mid-19th century, “one vast stretch of farm land.” It was not until the early 1880s, he pointed out, that real development took hold. Only a few years after those rows of houses were erected, many of them along the avenues and major streets were demolished as a new trend arose: residential hotels.

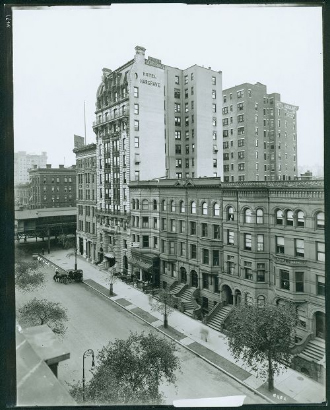

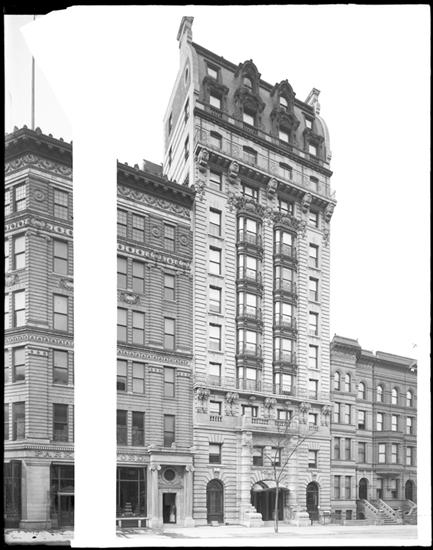

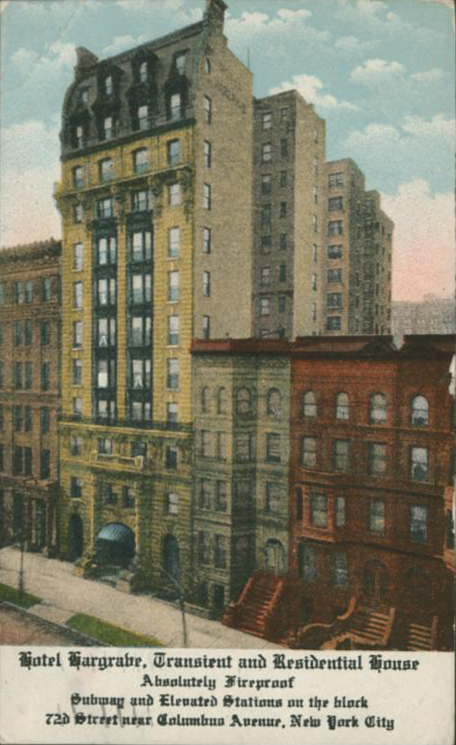

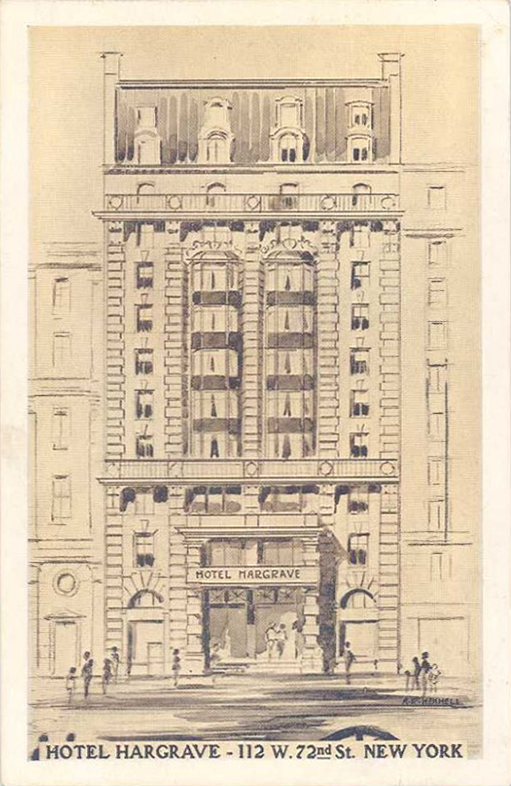

In 1901, George L. Felt commissioned architect Frederick C. Browne to design a 12-story hotel at Nos. 106 through 112 West 72nd Street. The property ran through the block where four brownstones, completed in 1884, faced 71st Street. Most likely inspired by the Parisian-type structures that had earlier begun arising along Broadway, Browne turned to the popular Beaux Arts style.

Completed in 1902, the Hotel Hargrave was a bit more restrained than its larger and grander Broadway counterparts—there were no heroic sculptures nor fruit-burdened garlands, for instance. Its brick and stone façade, however, did not disappoint. The rusticated stone base rose three stories to an iron-railed stone balcony supported by pairs of ambitious stone brackets. The six-story central section featured two curved copper-clad bays that culminated in frothy, carved cartouches. Another full-width balcony introduced the upper section, dominated by a double-height copper mansard.

The Hotel Hargrave extended, partly, through to 71st Street. When Henry L. Felt leased the new building to the Hargrave Hotel Company in March 1902, the paperwork noted that it included “the 16-foot house in the rear.” The management company, which agreed to pay $730,000 in total during its 21-year lease, had been organized specifically to run the hotel. The New-York Tribune noted the group “is controlled by a number of wealthy club men and one of the largest wholesale manufacturers of furniture in the city. It is to be fitted up elaborate, and will be rented as a high grade hotel. It will be managed by a man who at present runs one of the most prominent clubs in New-York.”

That manager was George Brown, who advertised the Hotel Hargrave as “New York’s most accessible hotel,” boasting the “six lines of transit, including Elevated and Subway express stations” nearby. Unlike the residential hotels, which were essentially high-end apartment houses without individual kitchens, the Hargrave was a “modern, high class family and transient hotel with superior appointments.” The distinction made it clear that travelers were welcomed as well.

The least expensive accommodations cost $2 per day—about $57 in today’s dollars. Brown marketed the hotel’s amenities saying it offered “superior appointments,” the restaurant service was “excellent,” and “fine music a feature.”

Thefts in turn of the century hotels were a constant problem and Brown apparently tried diligently to screen his potential employees. When 18-year old Louis Messier applied for a bellboy position early in 1903, he seemed the perfect fit. The young man came from a good Massachusetts family and he had graduated from a college in Montreal. The New-York Tribune noted that he “presented good recommendations.”

It was not long before police were searching for a hotel thief. Among the guests robbed was George H. Pursur, who discovered $1,050 in jewelry missing from his room. On February 23, 1903, two detectives entered Messier’s room at No. 248 West 45th Street. With Messier was 22-year old telephone operator John Cullen. The officers found $3,400 in stolen jewelry in Messier’s pockets and dresser drawer along with pawn tickets for almost that much more.

The Sun reported that Brown and other employees “saw that his arms were burned and swollen and that his face was purple.” The New-York Tribune added, “While waiting for the ambulance Depierre had an acute nervous attack, in which he constantly bit his finger nails, and the combined strength of the manager and a guest could not keep him from doing so.”

With Cullen’s arrest, his telephone operator position became available. It may have been Rene Depierre, working in that position the following year, who filled the spot. It was a job that nearly took Depierre’s life on August 26, 1904.

At around 3:00 that afternoon, after connecting two rooms, he placed his hand on the metal portion of the transmitter. According to the New-York Tribune, he “instantly feel to the floor, writing in pain.” George Brown rushed to aid him, while bellboys ran for doctors.

The Sun reported that Brown and other employees “saw that his arms were burned and swollen and that his face was purple.” The New-York Tribune added, “While waiting for the ambulance Depierre had an acute nervous attack, in which he constantly bit his finger nails, and the combined strength of the manager and a guest could not keep him from doing so.”

All the while, he was unable to speak and contorted his body as if in great pain. His condition became more exaggerated at the hospital. After a long period of continuous “massage treatment” he finally returned to normal. Depierre remembered that after making the connection he felt a “terrific shock” and felt “as if red hot irons” were being thrust through his body. After that, he remembered nothing.

The hotel electrician searched for the cause, but could find nothing wrong with the switchboard. His theory was a bit bizarre. He told a reporter “the telephone wires, which run underground to the hotel, may have become crossed with the Columbus avenue trolley wires, also underground.”

The Hotel Hargrave contributed in part to the women’s movement in 1905 when it was the scene of the organization of the Women’s Easter Golf Association on December 13th. The club continued to meet in the hotel for years.

The success of the Hotel Hargrave prompted Frederick C. Browne to be called back in 1905 to enlarge the building. The extension, completed in 1907, filled the entire 71st Street parcel. There were now 300 guest rooms, 200 baths, a restaurant, four electric elevators and its own electric and ice making plants.

Burglaries continued to be a problem; but one guest handled an incident with amazing calm. Samuel Fessenden was State Attorney of Connecticut and his family home was in Stamford. The family closed the house for the winter of 1906-07 and moved into the Hargrave.

While the family was at dinner on the evening of Saturday, February 16, the telephone rang. Fessenden’s daughter, Helen (“well known in Connecticut society,” according to the New-York Tribune) left the table to answer it. Just as she entered the darkened room, a dark figure holding a revolver stepped out of a corner and ordered her not to make a noise. He demanded that she turn over her jewelry.

Helen calmly explained that the family was in mourning and there were no jewels. None-the-less, she walked to a dresser and took two dollars from her purse, saying she was sorry that was all she had.

“Confound it, that’s just my luck!” growled the burglar in hushed tones. “This place looked good to me, and just because I am up against it and need the money there’s nothing doing. I won’t fall for two bones, so here’s your money back, and now, show me the way out.”

Helen led him to the fire escape but before he left she “remonstrated with him on the error of his ways,” according to the New-York Tribune. When she was sure he was gone, she returned to the dining room and informed the family. With the danger behind her, the reality of what had just transpired hit the feisty socialite. “Miss Fessenden was much unnerved by the incident, but soon regained her composure,” said the newspaper.

Living in the Hargrave at the time was Gustav J. Fleischmann, president of the Fleischmann Realty and Construction Company. Their mansion at 18 West 86th Street, which he would share with his brother and business partner Leon, as well as their parents Julius and Julia, was being completed.

Only a month after Helen Fessenden’s incident, on March 25, Mrs. Fleischmann noticed that a blue velvet jewelry box in her dresser had been tampered with. Missing were two diamond festoons valued at $6,000—more than $155,000 today.

The couple had hosted a dinner party for 12 guests the evening before. Mrs. Fleischmann became indignant when police asked about them. “Please do not refer to that. They were all friends, just a little party of friends, and they enter in no way into this affair. So say no more about them.”

Police knew for sure that whoever the thief was, he was in a hurry. He left behind $20,000 worth of diamonds, pearls and other gems in the same drawer; including a $15,000 diamond necklace, which had been only a few inches away from the lost festoons.

Suspicion fell on the Fleischmann’s two maids and the three hotel servants who had been in the apartment to clean. The police were confident it was “an inside job,” and noted that Mrs. J. Floyd Jones had recently been robbed of a $500 pearl necklace.

Annie Cronin, a 23-year old Hotel Hargrave maid, who had been hired in October, was arrested on what today would be considered rather flimsy grounds. One of the Fleischmann maids told Detective Price “she saw the Cronin woman standing near Mrs. Fleischmann’s dressing table Sunday morning.” The New York Times admitted “This is the only evidence so far against Annie.”

If indeed Annie Cronin was responsible for the robbery, she was far less professional than the burglar who made off with $5,000 worth of Martha H. Armitage’s jewelry on January 6, 1908. Called by police the Rope Ladder Hotel Thief, 21-year old James Lakin was arrested on February 24th. The daring robber was wanted for robberies and burglaries both in New York and in Boston for his four-month crime spree. He entered hotel rooms by dropping a rope ladder from the roofs.

Lakin confessed to the Armitage theft. In reporting on the arrest, The Sun mentioned “Mrs. Robert Tainer of the Hotel Hargrave was robbed of a quantity of valuables on February 16, but Lakin said he had no hand in it.”

Terror filled the hotel on November 22, 1911 when a massive explosion occurred on the corner of 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue, just feet away. A shanty had been erected there by sewer workers to hold dynamite. Because the sticks had become partially frozen, they were being “toasted” to thaw them out. The resultant explosion rocked the neighborhood, killed one man and injured several more.

The New York Times reported that the Hargrave “was the scene of intense excitement…Manager McGrath was in the lobby when he saw his windows go to pieces.” Almost all of the windows were blown out.

The telephone operator, Agnes Costello, “plugged every room in the house and gave a hasty assurance…that no one in the building was in danger,” wrote The Evening World. But guests were nonetheless shaken. Rubber manufacturer E. L. Goodlove was shaving at the time. “The shock threw his razor blade against his throat and inflicted a slight cut,” the World said.

And John A. McCarthy, here from Albany, was blown into his bathtub by the force of the blast. The New York Times lightened the mood by reporting “He was not hurt and showed his appreciation of the help accorded him by turning on the water and finishing his bath. It was the first time, it was said in the hotel, that a guest had been assisted at his bath by an explosion of dynamite.”

Perhaps the most infamous guest of the Hotel Hargrave was the former President of Nicaragua, General Jose Santos Zelaya. In November 1913 when he arrived in New York he was wanted by the Nicaraguan government for the murders of Sixto Pineda and Domingo Toribio.

According to officials, Zelaya was “plotting to return to power in Nicaragua.” He and his son, Macias, went to the Hotel Victoria, then slipped away to the Waldorf-Astoria. Discovering that he was being followed, he quietly checked into the Hotel Hargrave on November 20.

The New-York Tribune reported on November 25 “The Secret Service men followed the party to the Hotel Hargrave, and it was thought that the former dictator was trapped. But Zelaya has friends in New York.”

After staking out the hotel for some time, officials saw no trace of the fugitive. The Tribune reported “At the hotel desk it was learned that General Zelaya had not been seen about the hotel since Saturday night. It was thought that he might have left the place on Sunday. The baggage, the clerk said, was still in the house, but the hotel was being closely watched by Secret Service agents.”

It was later discovered that Zelaya had been spirited out of the hotel in a trunk. He was finally arrested in a friend’s apartment on West End Avenue. The Nicaraguan Government dropped its charges and allowed him to be released from The Tombs as long as he went to Spain.

Terror filled the hotel on November 22, 1911 when a massive explosion occurred on the corner of 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue, just feet away. A shanty had been erected there by sewer workers to hold dynamite. Because the sticks had become partially frozen, they were being “toasted” to thaw them out. The resultant explosion rocked the neighborhood, killed one man and injured several more.

In the years just prior to World War I the Hotel Hargrave was still upscale. An advertisement in October 1916 noted that it catered “only to a Discriminating Clientele.” A two-person suite of parlor, bath and bedroom cost $3.00 per night, or about $46 today. The same size apartment, rented full time in 1922, cost the equivalent of $2,667 per month today.

Prohibition brought frustration to many, if not most, Americans. One of those was Hotel Hargrave resident Harry Schloss, who attempted to take matters into his own hands. On July 10, 1924 The New York Times reported “The blockages against rum-runners in the estuary of the Shrewsbury River resulted yesterday in the seizure of 144 bottles of liquor found in a trunk and packing case that were being loaded on a truck from a steamboat, the Mary Patton.” Customs inspectors told reporters that the trunk was consigned to H. Schloss, Hotel Hargrave.” Harry could not be found when agents followed up at the hotel.

For years the widow Evelyn A Mossman and her son, John had lived a secluded life in the Hargrave. An invalid, she never left the apartment and spent no money. Reportedly she had no jewelry and only $25 worth of clothing. But the eccentric recluse was by no means indigent.

After she died in her apartment on November 19, 1925 a counsel for her estate discovered that banks and corporations had been searching for her for years. “Mrs. Mossman’s securities were so widely scattered and so neglected that many stocks had been called in long before her death and dividends on them ceased,” reported The Times. “Many bonds had unclipped coupons which had matured far back.” Because she never turned in retired stocks or collected interest on bonds, institutions had been trying to find her.

After two years of unravelling Evelyn’s tangled affairs, her estate included more than $1.1 million in securities, nearly $200,000 in bank accounts, and almost $67,000 in mortgages. It was estimated that son John would inherit $1.35 million—about 18 times that much today.

The Great Depression and changing taste negatively affected the Hotel Hargrave. Fussy Beaux Arts hotels had lost favor to modern Art Deco structures. Instead of the upscale suites of two decades earlier, a 1937 advertisement touted wicker-furnished rooms as “comfortable living at reasonable rates.”

A faded start living here at the time was Helen Lackaye. Born in 1883, she was known for her roles in such plays as Neal of the Navy in 1915, and The Knife in 1918. She appeared as late as 1928 in Revolt at the Vanderbilt Theater.

Helen was in private life Mrs. Agnes Helene Ridings. On October 19. 1940 she was returning home from Pennsylvania on a Baltimore & Ohio train. She became ill and was given first aid from a train attendant; but just as the train approached the Jersey City Terminal, Helen died.

Helen Lackaye would not be the last of memorable names from the theater to live in the Hotel Hargrave. In the fall of 1951 actor James Dean arrived in New York. According to his biographer Peter Winkler in the 2016 The Real James Dean, “Sometime later after meeting and beginning an intimate relationship with dancer Elizabeth “Dizzy” Sheridan, they rented a tiny, dilapidated room at the Hargrave Hotel.”

As the Columbus Avenue-72nd Street area underwent a renaissance in the 1970s, the bleak hotel got a make-over. On October 28, 1973 Robert E. Tomasson, writing for The New York Times, said “West 72d Street, a major commercial thoroughfare that has undergone a marked rejuvenation in the last few years is losing its last major eyesore, the 12-story former Hotel Hargrave near Columbus Avenue.”

Purchased a year earlier by Sackman Enterprises, it was undergoing a conversion to 183 apartments, ranging from studios to two bedrooms. A subsequent renovation, completed in 1989 converted the building to 66 condominiums.

While the ground floor has been somewhat altered and a beauty and hair case shop glaringly insults the once-proud French structure, the intact upper floors of the Hotel Hargrave are reminders of a time when the jewels of moneyed residents were constant temptations for the robbers.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

106-112 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 106-112 West 72nd Street: