Churrigueresque & Cherished Chows

by Tom Miller

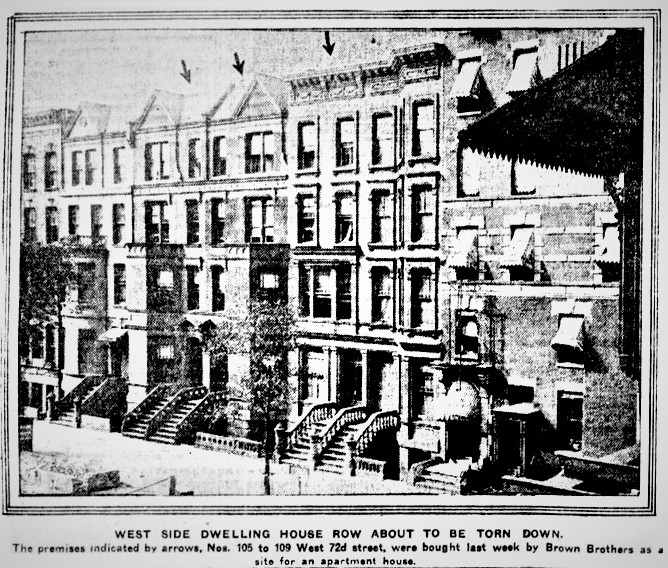

At the turn of the last century the 72nd Street blockfront between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues had been lined with four-story brick and brownstone houses for years. But residents of the Upper West Side were increasingly attracted to apartment house living and on July 28, 1912 the New-York Tribune reported that Brown Brothers Realty had purchased 105 through 109 West 72nd Street “as a site for an apartment house.”

Well-known apartment building architects George and Edward Blum were hired to design the 12-story structure which would cost a mind-boggling $300,000–more than $8 million in today’s money. Completed the following year, the structure was not given a name like almost all Upper West Side apartment buildings, but relied on its address alone, 105 West 72nd Street.

Although some architectural historians have called the Blum brothers’ style “churrigueresque”–an over-the-top version Spanish Baroque–the brick, stone and terra cotta ornamentation falls short of the frothy Churrigueresque Revival examples in, for instance, California. Nevertheless, the architects embellished the upper floors with romantic Spanish Baroque details. Interest was added by cast iron balconies at each of the tenth-floor windows, and by a full-width stone balcony one floor above. At the ground floor were two retail shops, the show windows of which smacked of the recent Art Nouveau style.

Potential residents could choose from four- or five-room apartments, each with a dining room, fireplace and a servant’s room. The names of the well-heeled residents appeared routinely in the society columns; and occasionally for less lofty reasons.

The smooth-talking Schinzel romanced Ruby May, promised to marry her, and brought her to New York where he “installed her in an apartment in West Seventy-second street.” Some months later Ruby May came to the humiliating realization that Schinzel was using her only for prurient reasons and had no intention of marrying her. She abandoned her apartment and sued him in April 1916 for $50,000 on the grounds of breach of promise.

Such was the case with Ruby May Blackmore, a 20-year-old woman from Florida, who moved in in 1915. Ruby May had been a “telephone girl” at a hotel in Jacksonville, where she lived with her widowed mother. There she became familiar with a guest, 27-year-old Henry E. Schinzel, who, according to The Sun, was “the son of wealthy parents in Detroit.” The smooth-talking Schinzel romanced Ruby May, promised to marry her, and brought her to New York where he “installed her in an apartment in West Seventy-second street.” Some months later Ruby May came to the humiliating realization that Schinzel was using her only for prurient reasons and had no intention of marrying her. She abandoned her apartment and sued him in April 1916 for $50,000 on the grounds of breach of promise. It was a sobering amount for the Lothario, more than $1 million today.

Ruby May Blackmore’s was the first of several rather scandalous incidents connected with 105 West 72nd Street that year. On March 4, the Evening Telegram reported that Dorothy Von Palmenberg had taken an apartment. Just a month later, she was being interviewed regarding the sensational murders of Hannah M. and John E. Peck.

Dr. Arthur Warren Waite had married their daughter Clara Louise on September 9, 1915. Four months later, in January 1916, he murdered Hannah and then killed John on March 21. In the interim, he had poisoned his bride, but she recovered. (It was all part of a rather excessive attempt by the doctor to enable him to carry on a romantic relationship with cabaret singer Margaret Horton.)

Because Dorothy Von Palmenberg was a close friend of Margaret Horton, she was called into the District Attorney’s office on April 23 for questioning. She offered little information other than, according to the New-York Tribune, “She said Dr. Waite had been planning a trip to Egypt with a woman companion.”

Another moneyed resident that year was Ethel Yerkes, a distant relative of multi-millionaire Charles T. Yerkes (she was a daughter of a nephew) who in 1906 had the equivalent of around $3 million today. Ethel was a close friend of Helen Elwood Stokes, wife of millionaire William Earl Dodge Stokes. The couple lived in the lavish Ansonia Apartments, built by Stokes. But things were not going well in their household.

When Helen returned from a trip to White Sulphur Springs in the fall of 1916, she went to Ethel Yerkes’s apartment rather than going home. Stokes came to the apartment on November 20 to discuss the fact that she did not want to return to their Ansonia apartment. The meeting turned violent. The details came out luridly in court during their divorce hearing.

Stokes testified, “She tore my face to shreds. One of the marks I carry now. She spat in my face and kicked my legs. Then she seized a knife and as I fled from her to the kitchen the cook came out and saved me.” Stokes’s attorney asked Helen, “You scratched good and plenty, didn’t you?” She replied, “I hope I did.”

The ugly and sensational affair dragged on for years. Helen Stokes stayed on in Ethel Yerkes’s apartment for some time. On June 9, 1923 The Morning Telegraph said that among the issues the grand jury would address was “whether the defendant [Helen] committed wrongful acts with ‘various men of unknown identity’ at 105 West Seventy-second street.”

In the meantime, Ethel Yerkes was married in her apartment on February 13, 1919. Her husband, Lieutenant Daniel Wooley of the U.S. Army was additionally the manager of the advertising department of Fleishmann Manufacturing Company. The newly-weds continued to live in Ethel’s apartment.

Also living in the building in 1916 was Sarah C. Doty, the wealthy widow of merchant James H. Doty. The elderly socialite was the vice-president of the Euterpe Club, a women’s group that hosted musical performances and “many charitable enterprises,” according to the New-York Tribune. She died in her apartment at the age of 71 on December 11, 1916, leaving her cherished Chow dog, Ah-See a diamond bracelet.

British-born Diana Norman (known as “Di”) lived here in 1923. The young widow was “well known in European society circles,” according to the Daily Standard of Watertown, New York. She unwittingly became involved in an international jewel heist after she became friendly with the dashing Maurice Friend, described by one newspaper as “Oxford graduate [and] possessor of several medals awarded to him during the world war for Heroism as a British cavalry officer.”

Stokes testified, “She tore my face to shreds. One of the marks I carry now. She spat in my face and kicked my legs. Then she seized a knife and as I fled from her to the kitchen the cook came out and saved me.” Stokes’s attorney asked Helen, “You scratched good and plenty, didn’t you?” She replied, “I hope I did.”

While he was “paying court” to her that summer, she noticed that a diamond and platinum bracelet worth $4,000 (around $60,000 today) was missing. She did not suspect Friend until sometime later when he gave her a check for $300, which turned out to be worthless. She had him arrested, and on August 2 The New York Times reported he had been found guilty and was to be deported to England. He told the judge “That would please me mightily, your Lordship.”

But there was much more to the story. Friend was suddenly linked to the missing Russian crown jewels. On October 5th, The Brooklyn Standard Union reported “Belief that the late Czar’s jewels can be located has been revived through the arrest of Maurice Friend…Miss Mable Sprague, probation officer, believes Friend knows the whereabouts of the jewels.”

During the Great Depression years, four-room suites were advertised at an affordable rent of from “$75 up,” or just under $1,450 per month today for the least expensive. The building continued to attract financially comfortable residents, like William E. Sennett, an executive with Twentieth Century-Fox Film Company, who lived here in the late 1930’s and early ’40’s. Sennett had been involved in the motion picture industry since the silent film days in 1916.

In the 1970’s the shops at ground level housed Stewart Ross’s Stone Free clothing store and the Westside Pet Shop. On December 31, 1984 The New York Times reported “After nearly half a century on West 72d Street–passed from father to daughter–the Westside Pet Shop was scheduled to close today.” The shop, opened by Japanese-born Goro Kuranuki in 1937, was an early victim to soaring commercial rents. Proprietor Elly Kuranuki said “I guess the new landlord has other plans. They won’t even talk about a new lease.”

The space became home to a shop that dealt in trendier items than birds and guinea pigs. Blades West sold and rented roller blades–the latest craze–and additionally offered “blading” instructions.

Ironically, given that the Westside Pet Shop Spot was forced out in 1984, today Spot Canine Club operates from one of the storefronts. The other store is home to a nail salon, Dashing Diva.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

105 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 105 West 72nd Street: