Bank at the Base, Smoke Police Upstairs

by Tom Miller

In real estate circles, Charles Buek was a sort of one-man show. His firm, Charles Buek & Co., not only developed properties, but he often acted as the architect as well. In 1887, he began construction of an upscale apartment building on the northwest corner of 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue. Completed the following year, he designed the brick and stone structure primarily in the recently popular Queen Anne style. The cost of construction was about $2.6 million in today’s money. Buek named the building the St. Charles Apartments.

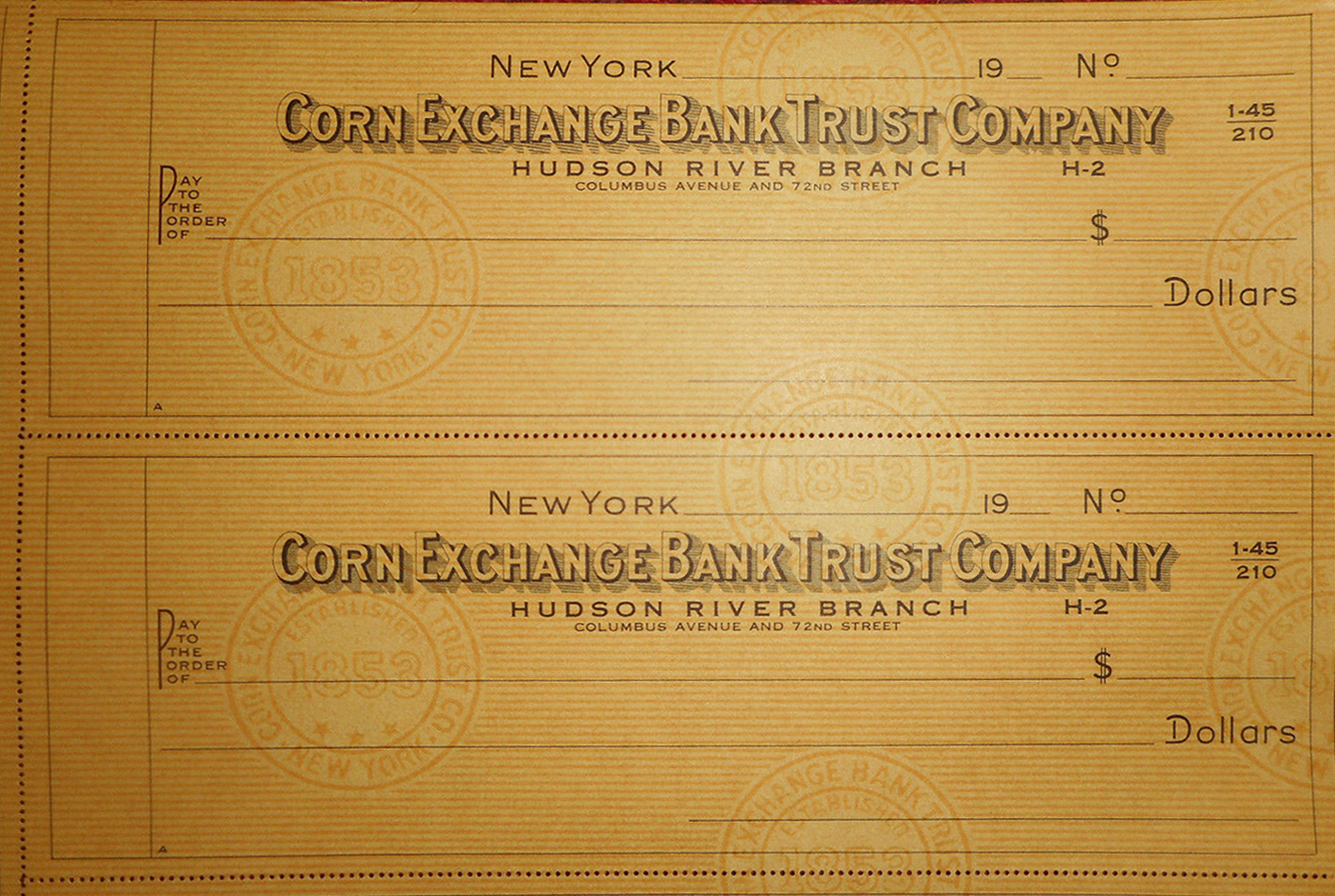

The 92-foot long Columbus Avenue side became home to the Hudson River Bank, while Charles Buek & Co. took the office space directly above as its headquarters. (The bank became the Corn Exchange Bank in 1899.) The upper floors held just one sprawling apartment per floor and rented for $1,800 per year—equal to about $4,000 a month today. An advertisement for one of them described:

A suite of rooms, consisting of parlor, dining room, five bedrooms and bath; steam heat and elevator; rooms all light and well ventilated.

Among the initial tenants was Mrs. Sarah Augusta Lynde Greenleaf, widow of Augustus Warren Greenleaf. Socially prominent, she shared the apartment with her three unmarried daughters, Alice Hazan, Sarah Houghton and Ida L. Greenleaf. Although Sarah was an invalid, she devoted much of her time and money to the development of Flushing Village. The Times Union said “She longed to see it the most beautiful of the suburban villages of New York.” Sarah died in the St. Charles apartment on April 20, 1892 at the age of 40.

Her sisters, still unmarried, joined the upper crust revolt against the Government’s March 1899 “Baggage Law.” It tightened the enforcement and examination of luggage and trunks of passengers on incoming steamships. Both women (who no doubt traveled to Europe regularly) signed the petition on April 11 that deemed the law “antiquated, profitless and vexatious.”

The Henry Davis family were also among the early residents. Included in the household was their “black-and-tan dog of high degree,” as described by The Sun. On October 8, 1893, the dog, along with Davis, his mother, his brother, two cousins and three other St. Charles residents were in court because J. Horwitz claimed the dog was his. Davis swore he had purchased the pet in San Francisco seven months earlier and had paid $3.87 for the collar it was wearing. Horwitz, who brought his three daughters, a son, a brother-in-law and his housekeeper to court, said he had bought the dog in Newark five months ago and had bills to prove it. Overwhelmed, the judge had the two families stand at opposite ends of the courtroom. Then the dog was placed in the middle to see which he would go to. “As soon as he was set free, however, the perverse brute snapped at the policeman’s heels and then attacked a tramp, at whom he barked until the court was in confusion.” Eventually the dog got down to business. He “trotted over and interviewed Horwitz and his friends, and then crossed the room to the Davis forces.” The judge gave up in despair and adjourned the case until he could come up with another way to determine rightful ownership.

Her sisters, still unmarried, joined the upper crust revolt against the Government’s March 1899 “Baggage Law.” It tightened the enforcement and examination of luggage and trunks of passengers on incoming steamships [but by West 72nd Street residents was] deemed the law “antiquated, profitless and vexatious.”

Without a doubt, the most colorful resident of the St. Charles was Dr. Charles Giffin Pease. He and his wife maintained a summer home, Sunset Lodge, at Mamakating Park, New York. Mrs. Pease was described by The Evening Telegram as “a prominent matron of the west side” and appeared in society columns for her receptions. But she could not compete with her husband for press attention.

A dentist, Pease was also a member of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, which prohibited him from using medications. The tenets got him into legal trouble in 1900 following the death of one of his patients, Helen C. Brush, from consumption. Not only was he not licensed to treat consumption, he did not report the infection to the Department of Health as was required by law. He explained himself in court.

“You think contagious diseases are only a belief?” asked the attorney.

“Yes.”

“You think that there is no such a thing as smallpox, and that it is only a belief?”

“Yes.”

Pease would become best known for his obsession with smoking. When he was one of 300 guests invited to a dinner of the New Yorkers Club at the Hotel Astor in February 1908, he responded saying he would be glad to accept but “he must have the assurance that none of the diners would smoke” as he believed “that womanhood is entitled to pure air unpolluted by the poisonous and irritating fumes of tobacco smoke.” The other invitees were informed of the no-smoking rule and, according to the New-York Tribune, “It went down hard with some of the guests.”

Soon Dr. Pease was a familiar figure in the nearest police station to the St. Charles as he routinely made citizen’s arrests in the 72nd Street subway station. He explained to a reporter following the arrest of Jay Greenwald on April 24, 1909. “Dr. Pease explained that he believed himself to be responsible for strict observance of the law prohibiting the smoking or carrying of lighted cigars or cigarettes in the subway.”

In September 1911, Pease took his mission a step further by forming the Non Smokers’ Protective League of America in his apartment. In reporting on the new group, The Sun called Pease “a dentist, who has had a lot of smokers arrested.” Readers of The Evening World may have raised eyebrows when Pease laid out his theory on smokers’ life after death.

When the smoker passes into the other life his craving for tobacco will continue, but he will not have the ability to gratify it. He will have a special hell of his own which will be a mixture of craving for tobacco and remorse for his indulgence in a habit which poisoned him and his fellow men.

In the meantime, other well-heeled residents included James A. Miner, vice-president of the Alpers Chemical Company, and his wife and son. The family occupied the fifth floor with their live-in servant, described by The New York Times as “a Japanese man.” Tuesday, September 29, 1903 was a day off for him. Miner was at work when his wife left around 1:00 in the afternoon. The Times reported “At 2:30 o’clock a Mrs. [C. J.] Mercer, who occupied a suite of apartments immediately above the Miners, smelled smoke.” She notified the janitor who used a pass key to enter the Miners’ kitchen.

A drawer filled with cloths had been set on fire. Also in the drawer was a box of gun cartridges, which had already begun to smolder. Alexander Phillips seized the box and doused it with water in the sink, then threw water on the burning drawer. There were four other fires burning in the Miner apartment. One, in the center of the parlor, was “within two feet of a valuable piano.” The five fires were extinguished before causing serious damage. When Mrs. Miner returned home she searched for missing items and found that only the silverware that was not monogrammed had been taken.

The decades had not dulled Pease’s ability to produce a controversial comment. “His rigid abstinence has given to him the power of spiritual healing, Dr. Pease told the reporter.” He said, “People are healed just by thinking of me.”

When their son died later that year, the couple was emotionally devastated. They closed their St. Charles apartment and went to Europe for an extended stay. They returned on September 6, 1904 but could not bear to come home to their apartment. Mrs. Miner went to Hornellsville, New York, where a married daughter lived, and James took rooms at the Grand Hotel.

Mrs. Miner urged her husband to retire and leave New York. He finally conceded and on September 16 wrote his wife a letter saying he informed his partner, Dr. William C. Alpers, and would be leaving the next day. But he was found dead in his bed the following evening after a fatal heart attack.

On December 4, 1934 The New York Sun reported “Dr. Charles Giffin Pease, who believes people should eat and drink anything they like with the exception of meat, alcohol, tea, coffee, cocoa and other deadly poisons, but who is ardently opposed to the consumption of tobacco, opened the door himself in answer to the reporter’s ring.” That reporter had come to the St. Charles apartment to interview the doctor on his 80th birthday. A party in the apartment “which Dr. Pease has occupied for forty-five years or so,” was scheduled for that evening.

The decades had not dulled Pease’s ability to produce a controversial comment. “His rigid abstinence has given to him the power of spiritual healing, Dr. Pease told the reporter.” He said, “People are healed just by thinking of me.”

Following a renovation completed in 1951 there was still a bank on the ground floor, with its offices on the second; but the sprawling apartments had been divided into two per floor. Today, as was the case in 1888, a bank occupies the ground floor. And overall, little has changed externally to the St. Charles Apartment building when it first opened.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

101 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 260-268 Columbus Avenue / 101 West 72nd Street: