A Grocery or a Work of Art?

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

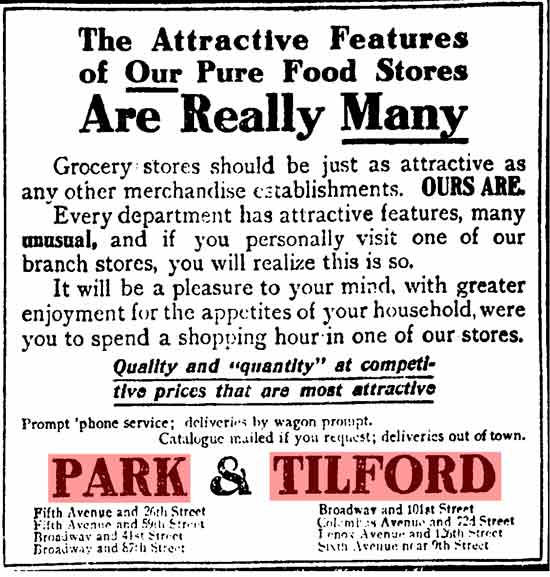

In 1840 25-year old John M. Tilford partnered with Joseph Park to form “in a small way,” as described by Men of the Century in 1896, the grocery store named Park & Tilford. By 1886 Park & Tilford had four New York stores as well as a branch in Paris (used mainly for merchandising and exporting). The term “grocery” had little to do with the word we commonly use today. Park & Tilford catered to the carriage trade and stocked a dizzying array of goods–wines, confectioneries, gourmet foods and delicacies, cigars, and personal items. The New York Times deemed Park & Tilford “The very beau ideal of what a first class grocery store should be.”

The year following John Tilford’s death in January 1891, his son, Frank, recognized the developing Upper West Side as a prime location for yet another store. In March 1892 the firm purchased the one-story business building at the southwest corner of Columbus Avenue and 72nd Street. The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported, “Park & Tilford will shortly commence the erection of the fire-proof building…to be used entirely for their business.”

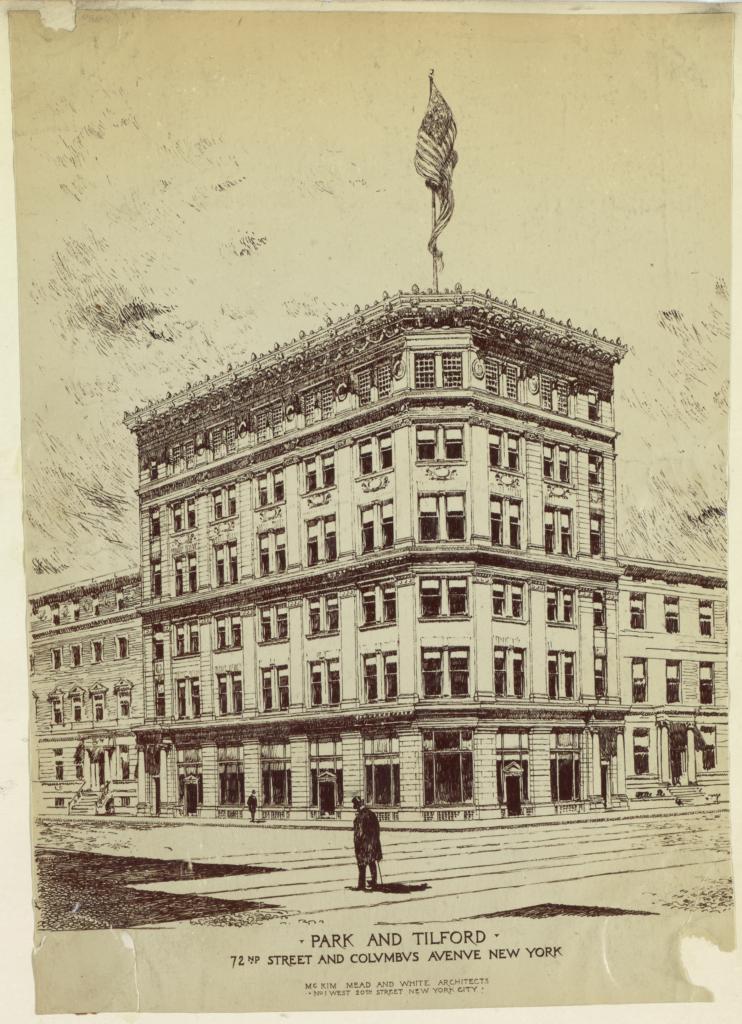

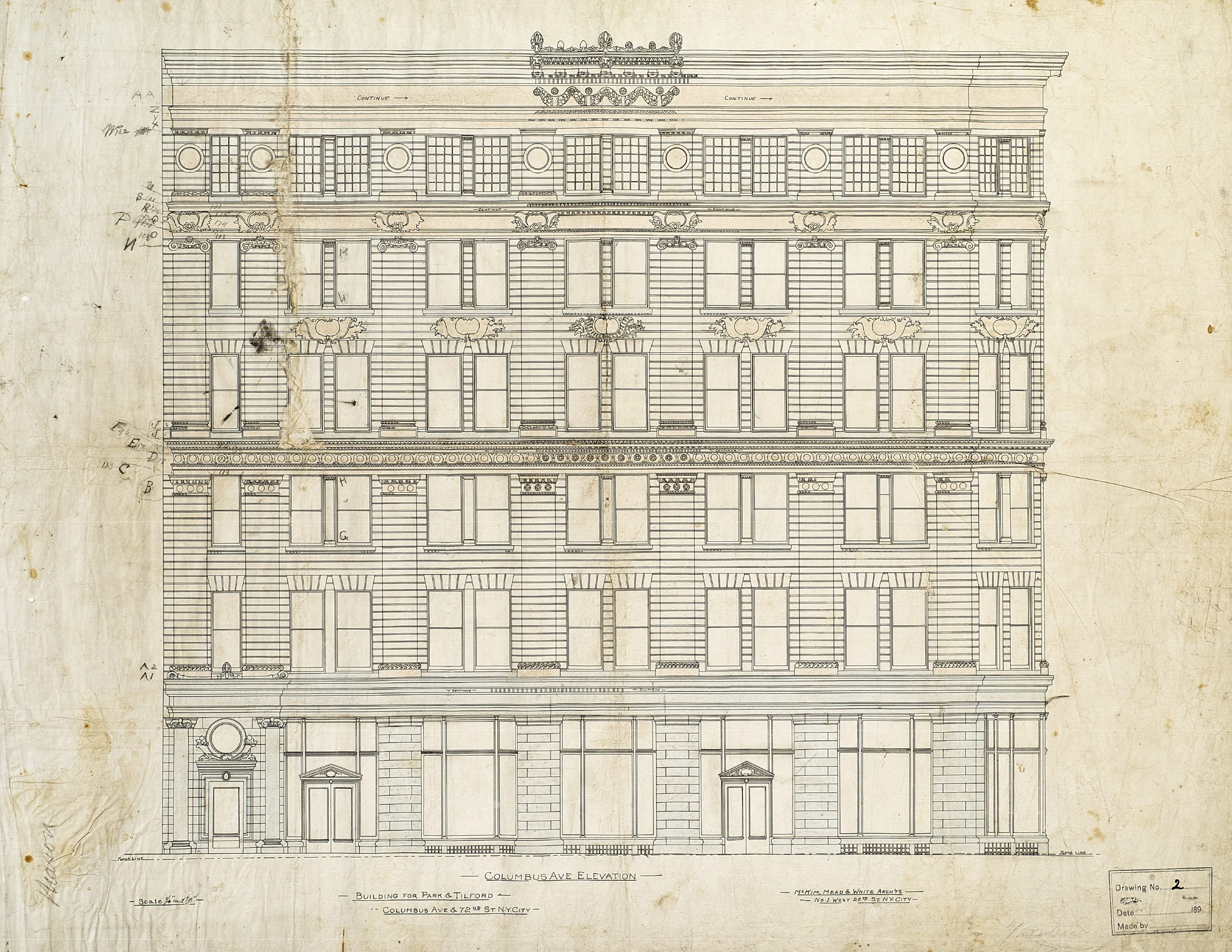

McKim, Mead & White received the commission to design the new structure. The firm filed plans on April 22 for a “six-story brick, stone and terra cotta building” to cost $85,000 (more than $2.25 million today).

The Renaissance Revival style building opened on September 23, 1893 and, according to The Times, “was attended by hundreds, who admired the building and the artistic display of goods.” The article added, “There is no business building more handsome on the west side” and the New-York Tribune called it “a decided architectural ornament to the neighborhood.”

The Tribune noted that the “best class of trade” on the Upper West Side had “suffered much inconvenience by being obliged to order their groceries and household provisions from down-town houses.” They could now rest easy. “This inconvenience will be no longer felt, for the new store of Park & Tilford…is as complete and perfect in every detail as the most exacting buyers can demand.”

Park & Tilford’s vast array of merchandise was hinted at in the Tribune‘s reporting that the new store “is completely stocked with the best quality of standard articles, including a most desirable and extensive assortment of superior perfumery and toilet requisites.” The newspaper said, “The ground floor of the building has been decorated and stocked in such a manner that it is no exaggeration to say that it is a work of art.”

“Almost 300 employees of Park & Tilford, scattered over six floors, gave an excellent demonstration of the fire drill system. Summoned by a series of signals, the employees, most of them women, formed in line and marched through the smoke and fumes without disorder to the street.”

Below the Park & Tilford store were a basement and sub-basement. Here behind-the-scenes work went on, like the candy-making shop. In July 1909 the Cold Storage and Ice Trade Journal reported that the firm had improved its “candy factory” with a 10-ton refrigeration machine. The up-to-the-minute addition would have nearly deadly consequences later.

On the afternoon of December 17, 1916 six men working in the sub-cellar discovered a fire and pulled the alarm, but before they could reach the exits an ammonia tank to the refrigeration system exploded. The New-York Tribune reported, “All managed to crawl to the stairs or elevators before collapsing. They were found by volunteers among their fellow employees and dragged to the street.”

As fire fighters responded, more ammonia tanks exploded. The first group of seven reached the sub-cellar with a line of hose, and then tried to retreat. “All dropped before reaching the elevator,” said the article. A second wave, from Hook & Ladder 40, headed towards the fire and came across them. But, “by the time they were hauled to the street most of their rescuers were overcome.”

Fire fighters worked in shifts, covering their faces with wet towels–half fighting the fire and the other half pulling stricken firemen to the street. Deputy Chief Burns finally refused to allow any more men to enter the building. It was new fire fighting technology that saved the building. “Captain McElligott and his oxygen helmeted men worked their way into the smoke and fumes filled cellar with a line of hose, but it was a half hour before they had cleared the air sufficiently to permit the other firemen to enter.”

In the meantime, the Tribune praised Park & Tilford’s emergency preparation and the discipline of the employees. “Almost 300 employees of Park & Tilford, scattered over six floors, gave an excellent demonstration of the fire drill system. Summoned by a series of signals, the employees, most of them women, formed in line and marched through the smoke and fumes without disorder to the street.”

Park & Tilford sold the building in 1920. In 1925 architect Bernard Hersbrun was hired to renovated it to what became known as the Papae Building. There was now a bowling alley in the basement, stores on the first floor, and offices and meeting rooms above.

The meeting rooms were routinely leased by clubs and union groups. In December 1932, for instance, the election of officers of the Boston Terrier Club of New York was held here; and the following July the New York State Association of Retail Meat Dealers met to discuss a 48-hour work week and minimum wages.

On February 13, 1934, two months after Prohibition was repealed, The New York Times reported that the Retail Druggists Association of New York and the Pharmacy Owners Association had met in the Papae Building. Surprisingly today, the reason for the meeting was to compose a letter to Governor Herbert Lehman “with a plea that he permit the sale of liquor in the drug stores.” The group, representing 5,000 pharmacies, said they were in “imminent peril” unless “drug stores were permitted to sell alcoholic beverages under the same license system that now governs the liquor dealers.”

Considering all the union meetings being held in the building, it was not surprising that Cafeteria Local Union 460 of the I. W. W. leased an office in 1933. What was surprising was that the “union” had only one member, 22-year old Arthur Fried.

The artful con artist studied up on labor unions in the library, printed letterhead and rented the office. Then, according to police in January 1934, “he called on cafeteria owners, commanded them to pay their help ‘union’ rates and when they refused, hired sandwich men at $1 a day to picket their places.” For a $25 payment Fried would call off the business-deflating picketers. Fried’s scheme actually worked. Until Nathan Brandwine called the police. It was the end of the one-man Cafeteria Local Union 460. Fried was arrested and charged with attempted extortion.

The Retail Druggists Association of New York and the Pharmacy Owners Association had met in the Papae Building. Surprisingly today, the reason for the meeting was to compose a letter to Governor Herbert Lehman “with a plea that he permit the sale of liquor in the drug stores.”

The Socialists of the Seventh and Ninth Assembly Districts held its meetings in the Papae Building in the early 1930s. But a far different type of assemblage drew police attention in the spring of 1935.

To gain entrance to a large, private space on the sixth floor, a visitor needed an admission card. One was obtained by a plainclothes patrolman in March and he was shocked by what he uncovered. At 10:45 on the night of March 12 the place was raided. The audience, the management and the performers–150 people in total–were arrested for “participating in or attending an indecent performance.”

The New York Times explained, “the performance consisted of indecent motion pictures, after which performers started an improper presentation.” It required several back-and-forth trips by patrol wagons to transport the arrested throng. All but one of the girls performing were in their teens, the oldest being 20. Three of them, who were waiting to take part in the performance, escaped.

By the last quarter of the 20th century the neighborhood of Columbus Avenue and West 72nd Street had severely declined. But on October 28, 1973 Robert E. Tomasson, writing for The New York Times, called West 72nd Street “a major commercial thoroughfare that has undergone a marked rejuvenation in the last few years.” Part of that rejuvenation was the 1972 renovation of the Park & Tilford building to apartments.

McKim, Mead & White’s ground floor had been obliterated by now so an architecturally sympathetic replacement of fluted pilasters was installed. The Park & Tilford building, where well-to-do shoppers browsed among champagne and imported French delicacies, still commands a dignified presence.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

100 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 100 West 72nd Street / 248-246 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Elena Jovan

& Nadia Nichol!