Land Covenants and Seized Property

by Tom Miller

Frederick Law Olmsted’s rambling Riverside Park was begun in 1875 and would take a quarter of a century to complete. The naturalistic park with its wide drive and breathtaking vistas across the Hudson River was expected to lure wealthy homeowners away from Fifth and Madison Avenues. Riverside Avenue, later renamed Riverside Drive, began at 72nd Street and upon completion would follow the curving topography north to 129th Street.

In 1899, the park and drive were essentially completed and Frederick Charles Prentiss and his wife, Lydia, considered the area as the location for their new home. The land at the curving corner of 72nd Street and Riverside Drive was owned by John S. Sutphen, Sr. Sutphen would build his own home at the southern corner of the oddly-shaped lot and intended his neighborhood to be strictly exclusive.

He was, actually, carrying on the restrictions on the land that were in place when he purchased it. Going back to 1867, the deeds carried an extensive list of prohibitions. Included was the ban on erecting a slaughterhouse, brewery, livery stable, carpenter shop, nail factory, sugar refinery, menagerie “or any other manufactory, trade business, or calling which may be in anywise dangerous, noxious, or offensive to the neighboring inhabitants.” The covenant was “binding upon all the future owners.”

Going back to 1867, the deeds carried an extensive list of prohibitions. Included was the ban on erecting a slaughterhouse, brewery, livery stable, carpenter shop, nail factory, sugar refinery, menagerie “or any other manufactory, trade business, or calling which may be in anywise dangerous, noxious, or offensive to the neighboring inhabitants.”

As Sutphen entered negotiations with the Prentisses on April 3, 1899, he added further stipulations. Within two years of April 3, they were to have completed a “first class building adapted for and which shall be used only as a private residence for one family.” Sutphen went further by dictating that residence must “conform to the plan thereof made by C. P. H. Gilbert, Architect.” By assuring that all his buyers would use the same highly-esteemed architect, Stuphen guaranteed that his neighborhood would be both harmonious and high-class.

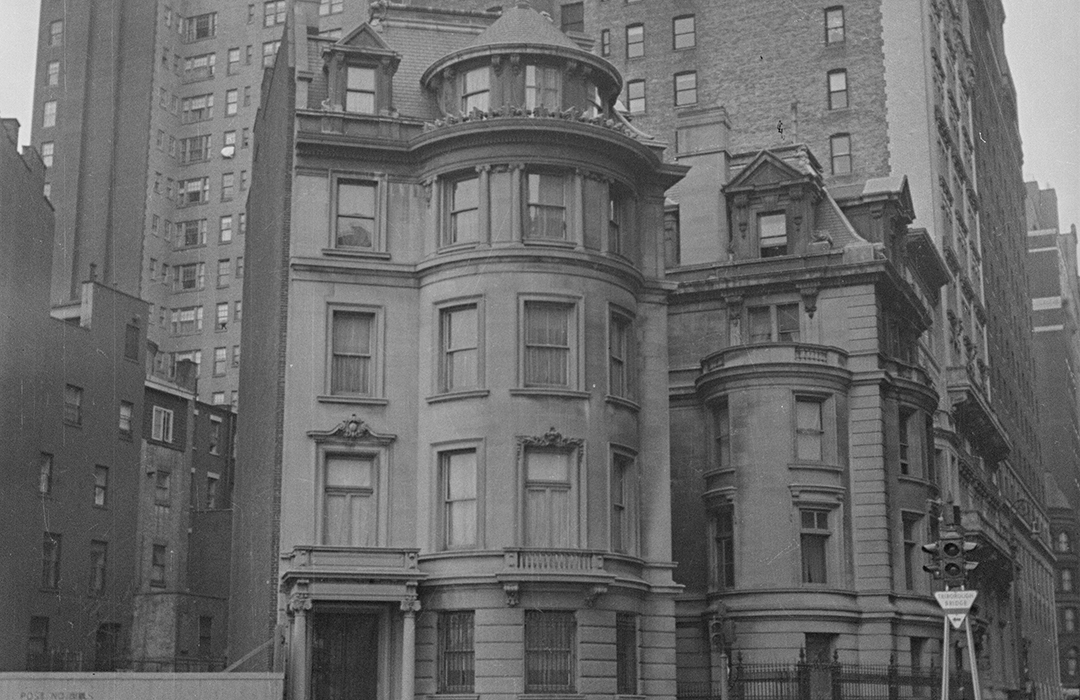

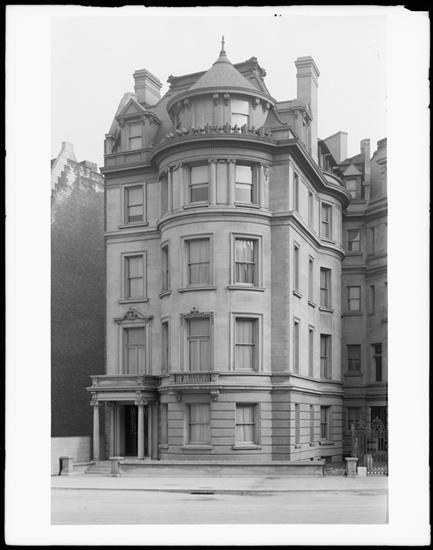

Gilbert took full advantage of the curving site, separating the Sutphen and Prentiss houses with a wedge-shaped yard. Five stories tall, the limestone-clad mansion featured an American basement, the height of fashion at the time. Guests entered through a portico with Ionic columns above a short flight of steps. From its rusticated base the Beaux Arts house rose to a magnificent mansard that sprouted a squat turret, tall chimneys, pedimented dormers and balconies. Gilbert followed the curve of the drive with a bowed façade and took advantage of the odd lot to provide a full wall of windows on the southern, garden side.

The Sutphens and Prentisses not only shared a garden, but a common wall towards the rear of the houses. A Party Wall Agreement would regularly be renewed by the two property owners, as documented repeatedly in the Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide.

The Prentiss family included two daughters, named after their parents, Frederica Carlotta and Lydia Floyd. Young Lydia took her middle name from David Gelston Floyd, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and an ancestor on her mother’s side.

Five years after the house was completed the first of debutante entertainments began. On January 9, 1904, Lydia gave a reception for Frederica followed by “a large party and dinner” as reported in the New-York Tribune the following day. Despite their introductions to society, the Prentiss girls made it obvious that they were in no hurry to marry.

The socially prominent Lydia S. F. Prentiss would be pressed into an uncomfortable decision regarding the tone of the neighborhood in 1916.

The restrictions on the homes on the former Sutphen property were challenged that year when Dr. William H. Wellington Knipe leased the former home of William Guggenheim at 3 Riverside Drive. His lease cost him $4,000 a year for the first year, $5,000 a year for the next four years-a hefty $75,000 by today’s standards. The house was separated from the Prentiss residence by that of Mrs. Angie M. Booth.

Dr. Knipe was “one of the first physicians in New York to become interested in twilight sleep,” said The Sun on January 22 that year. “Twilight sleep” was a procedure used on women going into labor that was intended to reduce the pain of childbirth. Lydia Prentiss’s flanking neighbors, Mrs. Booth and Mrs. Mary T. Sutphen, were outraged when Dr. Knipe established his “twilight sleep” sanitarium in the Guggenheim residence. They filed suit to stop him.

“The plaintiffs contend that the block is restricted to residential purposes and barred from trade and business,” said their lawyer. The doctor said the neighbors were “needlessly alarmed” and “said he had talked with many of his neighbors and they told him they preferred the proposed sanitarium to the ‘exclusive’ boarding house formerly conducted here,” reported The Sun.

Lydia Prentiss was placed in an uncomfortable position when her neighbors knocked on her door, asking her to join them as a plaintiff in the lawsuit. The stalwart socialite held her ground, however, telling the press she “didn’t think women should lend themselves to opposing the development of any treatment that would alleviate or diminish the pains of childbirth.”

“The plaintiffs contend that the block is restricted to residential purposes and barred from trade and business,” said their lawyer. The doctor said the neighbors were “needlessly alarmed” and “said he had talked with many of his neighbors and they told him they preferred the proposed sanitarium to the ‘exclusive’ boarding house formerly conducted here,” reported The Sun.

One might imagine that Lydia was absent for afternoon tea in either of her neighbor’s parlors for some time.

The following year, on September 14, 1917, and 13 long years after her daughter’s debut, Lydia announced the engagement of Frederica to architect John Theodore Hanemann. On Saturday afternoon, January 12, 1918, the couple was married in the Riverside Drive mansion by the Bishop of Pittsburgh, the Right Rev. Courtlandt Whitehead. The Sun reported that the newlyweds “after their wedding trip” would live at 334 West 72nd Street, “the house being a wedding present from the bride’s parents.”

After her parents died, Lydia Floyd Prentiss lived on in the Riverside Drive mansion with her small staff of servants. The aging spinster clung to her impressive colonial pedigree, being a member of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Colonial Lords of the Manors. She devoted her time to medical causes, sitting on the board of managers of St. Luke’s Hospital for the Aged, and for many years volunteering in St. Luke’s.

It was in that same hospital that she died after a prolonged illness on February 27, 1955. A year later, almost to the day, the Nippon Club purchased the house. The only exclusive gentlemen’s social club for wealthy Japanese Americans, it had been founded in 1905. The club had been housed in a striking mansion built for the group in 1912; however after the bombing of Pearl Harbor the United States Government seized the property.

The Nippon Club did not stay long, and in 1957, it sold the house to the New York Mosque Foundation, Inc. The group had been organized by Manhattan’s Muslim community in 1952 to raise funds for the construction of a mosque. As planning progressed, the Foundation filed plans to renovate the first two floors of the mansion into a “mosque assembly and kitchen” on the first floor, and a “mosque prayer room” on the second. The third and fourth floors were renovated to one apartment each, and the fifth floor was “to remain vacant.”

The foundation’s $17 million mosque at 1711 Third Avenue finally opened on April 15, 1991 after significant delays. The Prentiss house continued to be used for prayer as a “satellite location.”

Although it might use a good cleaning, the Prentiss mansion at No. 1 Riverside Drive is scarcely changed since the family moved in over a century ago. Home to only one family during its residential life, it survives as a reminder of when shirtwaisted women and bowler-wearing men bicycled along a drive lined with mansions.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

1 Riverside Dr., The Prentiss Residence

Landmarks Timeline

Next Stop

Designation Report

Meet Mamemaname Ndlaye