65 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

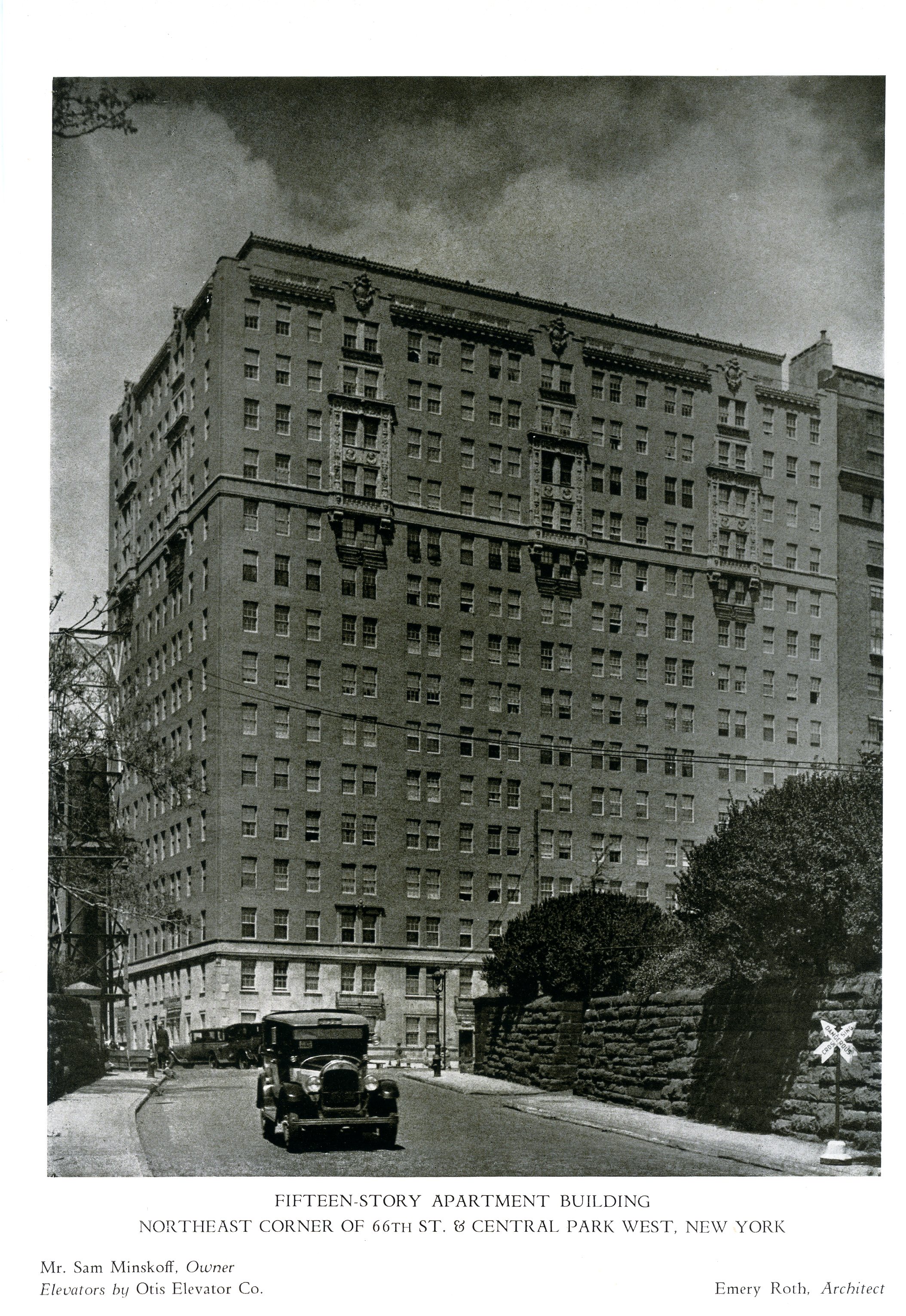

The 1920’s saw Central Park West transformed as late Victorian residential hotels and at least one theater made way for the streamlined, Art Deco apartment buildings that would define the upscale thoroughfare. But esteemed apartment building architect Emery Roth had a different style in mind when he received the commission to design a 15-story structure at the northwest corner of 66th Street for the estate of George B. Leonard. Completed in 1927, Roth’s tripartite, neo-Renaissance style building scoffed at Art Deco geometric motifs and ziggurat-like towers. He embellished the entrance with complex Renaissance-inspired carvings; placed ornate, double-height pseudo balconies at the 12th and 13th floors; and interrupted the terra cotta cornice at intervals with stepped parapets and enormous crests.

The building ignored tradition in another way, as well. Beginning with the 1884 Dakota, apartment buildings along Central Park West were given names. This one, however, went by its address, 65 Central Park West, more in keeping with the buildings on the opposite side of Central Park.

Potential residents could choose from a variety of apartment sizes, from as small as three rooms to sprawling duplexes. They filled with respectable, white collar residents, among the earliest of which was retired Supreme Court Justice Max Warley Platzek (who went by his first initial and middle name).

The life-long bachelor (he was 73 years old in 1927) had been the legal consul to Tammany Hall in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was elected to the New York State Supreme Court bench in 1906, holding that position until forced by law to retire at the age of 70 in 1924.

It was not for a reception or dinner party that the names of one young couple, David and Virginia Schwartz, appeared in The New York Sun on March 21, 1933, but for a more cringeworthy reason. Twenty-nine year old Virginia had taken their dog along with her on a Midtown shopping excursion. As they passed the Hotel Gorham on West 55th Street, Frances Dunn exited the hotel with her dog. Somehow the society women became engaged in a rancorous back-and-forth about which was the better dog. The New York Sun reported, “A dispute between two young women as to the merits of their respective dogs ended in the West Forty-seventh street station early today after having been contested bitterly by the animals and their owners in the lobby of the Hotel Gorham.”

…among the earliest [residents] was retired Supreme Court Justice Max Warley Platzek

As the argument became more heated, according to hotel employees, “Mrs. Schwartz urged her dog to attack Mrs. Dunn’s dog.” Frances Dunn retreated with her pet into the lobby, closely followed by Virginia Schwartz and hers. Witnesses told police, “once in the lobby the women and dogs became engaged in a general altercation.” Frances Dunn got the worst of it, ending up on the floor with a black eye. Hotel employees called the police and both women were taken to the station house. There Frances Dunn filed charges against Virginia Schwartz. She was held until her husband arrived with the $500 cash to bail her out.

Living at 25 Central Park West during the 1930’s were the director of exhibits and concessions of the New York World’s Fair, Maurice Mermey; and treasurer of the Port of New York Authority since its creation in 1921, William Leary. Having started his career in advertising in 1887, Leary had been campaign manager for Theodore Roosevelt’s unsuccessful run for New York City mayor. He remained close friends with Roosevelt until the former President’s death in 1919. Before Leary’s appointment to the Port Authority, he had been secretary of the Park Department.

Former Municipal Court judge Leopold Prince took an apartment in February 1940. He would remain until his death on August 17, 1951. In 1941 playwright Elmer Rice and George Coulon signed leases. Elmer Rice had just separated from his wife, Hazel Levy. Following his divorce the following year, he married actress Betty Field. The couple would have three children, John, Judy and Paul.

Born Elmer Lopold Reizenstein in 1892, Elmer Rice’s career was lackluster until his 1923 The Adding Machine. Described by critic Brooks Atkinson as “the most original and brilliant play any American had written up to that time,” Rice had knocked the play out in just over two weeks. By the time he moved into 65 Central Park West, he was a force in the theatrical community. While living here his 1945 Dream Girl was produced, as well as his final play, the 1958 Cue for Passion.

The Rice apartment was filled with an impressive artworks. Despite his relatively humble beginnings, Rice’s collection of modern paintings included works by Klee, Picasso, Modigliani, and Braque to name just a few.

Although the United States was not directly involved in World War II when George Coulton signed the lease on his six room apartment in October 1941, his home country of France most certainly was. In reporting on his lease, The New York Times noted that he “is engaged in refugee work here.”

Two months after Coulton moved in, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States was pulled into the conflict. American socialites threw themselves into various war efforts. Doing her part was Anne Weg, the wife of Dr. Nathaniel Weg, who became a member of the American Women’s Voluntary Services salvage committee.

Anne came from the old New York De Rham family, and had been head of the Abraham & Straus decorating department for 17 years before opening her own interior decorating shop on East 57th Street in 1939. Now, although more accustomed to hosting card and dinner parties, she and other members spent one day a week riding on Department of Sanitation trucks to collect tin cans for recycling for the war effort. The Sanitation Department employees did their best to make their unlikely co-workers comfortable. On September 2, 1942, The New York Sun said the trucks had a “mirror-like sheen,” the cabs “had been neatly re-upholstered in brown paper,” and the driver and his helper of the truck in which Anne Weg rode “had even gone so far as to buy new work gloves.”

Banker Lazar I. Estrin and his family lived at 65 Central Park West at the time. A vice-president of the Irving Trust Co., he left his native Russian in 1916, fleeing the political upheaval there. He and his wife, the former Helen Vishniac, had two daughters, Anne Eugenie and Lucy.

The Estrin girls received the best of educations. Anne graduated from the Berkeley Institute, and received a master’s degree from Swarthmore College in 1943, and another in social work from Columbia University. Lucy Estrin Kaveler graduated magna cum laude from Oberlin College in Ohio and did post-graduate work at Columbia University. She would go on to an illustrious career as an editor and author, receiving numerous awards.

Among the most fascinating residents of 65 Central Park West was Eunice Roberta Hunton Carter. She and her husband (one of the first Black dentists in New York City) Lisle Carter Sr. had one son, Lisle, Jr. Eunice was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1899. She became the first Black woman to earn a law degree from Fordham University, and passed the New York bar examination in May 1933. Only two years later, she became the first Black female assistant district attorney in the State of New York.

Convinced that mob boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano was involved in prostitution, she initiated a wide-spread prostitution racketeering investigation and successfully urged District Attorney Thomas Dewey to prosecute the case. Up to this time, the state had been successful only in convicting organized crime leaders for tax evasion. Because of Eunice Carter’s groundwork, Luciano was sentenced to 10 years, and then was deported.

[Eunice Roberta Hunton Carter] and her husband (one of the first Black dentists in New York City) [lived here]

Her list of firsts continued. Eunice Carter was the first observer from the National Council of Negro Women to attend the United Nations organizational conference in 1945. She served as vice president of the National Council of Women of the United States from 1949 to 1967, and sat on the national board of the Young Women’s Christian Association.

Lisle Carter, Jr. went on to a law career, as well. He would serve in the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson administrations as Assistant Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, and later as a vice president of the Urban Coalition.

While still living at 65 Central Park West, Eunice Hunton Carter contracted cancer. She died in the Knickerbocker Hospital on January 25, 1970.

In 1995 the building achieved its own celebrity status, briefly anyway, when it was featured in the television series Central Park West. An attempt to ride the coattails of primetime soap operas like Dallas and Knots Landing, it starred Mariel Hemingway, Mädchen Amick, and Kylie Travis. The series was cancelled in 1996.

The well-heeled residents of the building could not have been more shocked when 76-year-old Dr. Irene Shapiro was arrested on the sidewalk in front of 65 Central Park West on January 14, 1998. She and her late husband had moved into the building in 1970, and had a private practice in a ground floor office. Following his death in the 1980’s, she remained in their apartment and carried on the medical practice.

But Irene Shapiro, described by other residents as a “lovely old lady,” was dealing drugs. She was arrested when she sold four prescriptions to an undercover officer that afternoon. One resident told The New York Times, “She was nothing but a solid citizen here. It’s a horror story if it’s true.”

Emery Roth’s 1927 building that refused to fit the mold continues its low profile existence. Unlike other Central Park West apartment buildings, no flashy movie stars have made headlines from here. Other than one elderly woman selling drugs, 65 Central Park West draws no negative press, its upscale residents quietly coming and going.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE