55 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

For decades The Courtney and The Georgian Court had stood at the southwest corner of Central Park West and 66th Street. Like other resident hotels along the swanky street, their residents enjoyed spacious suites. A 10-room, 3- bath apartment in The Courtney rented for up to $4,500 a year in 1922–about $5,500 a month today.

But the 1920s saw Manhattan’s lavish private homes and fussy Victorian resident hotels losing favor to modern apartment buildings. Scores of smaller buildings were razed and replaced by Art Deco behemoths. On April 6, 1930, The New York Times noted “Central Park West will witness the opening this year of about half a dozen new structures all covering large plots.”

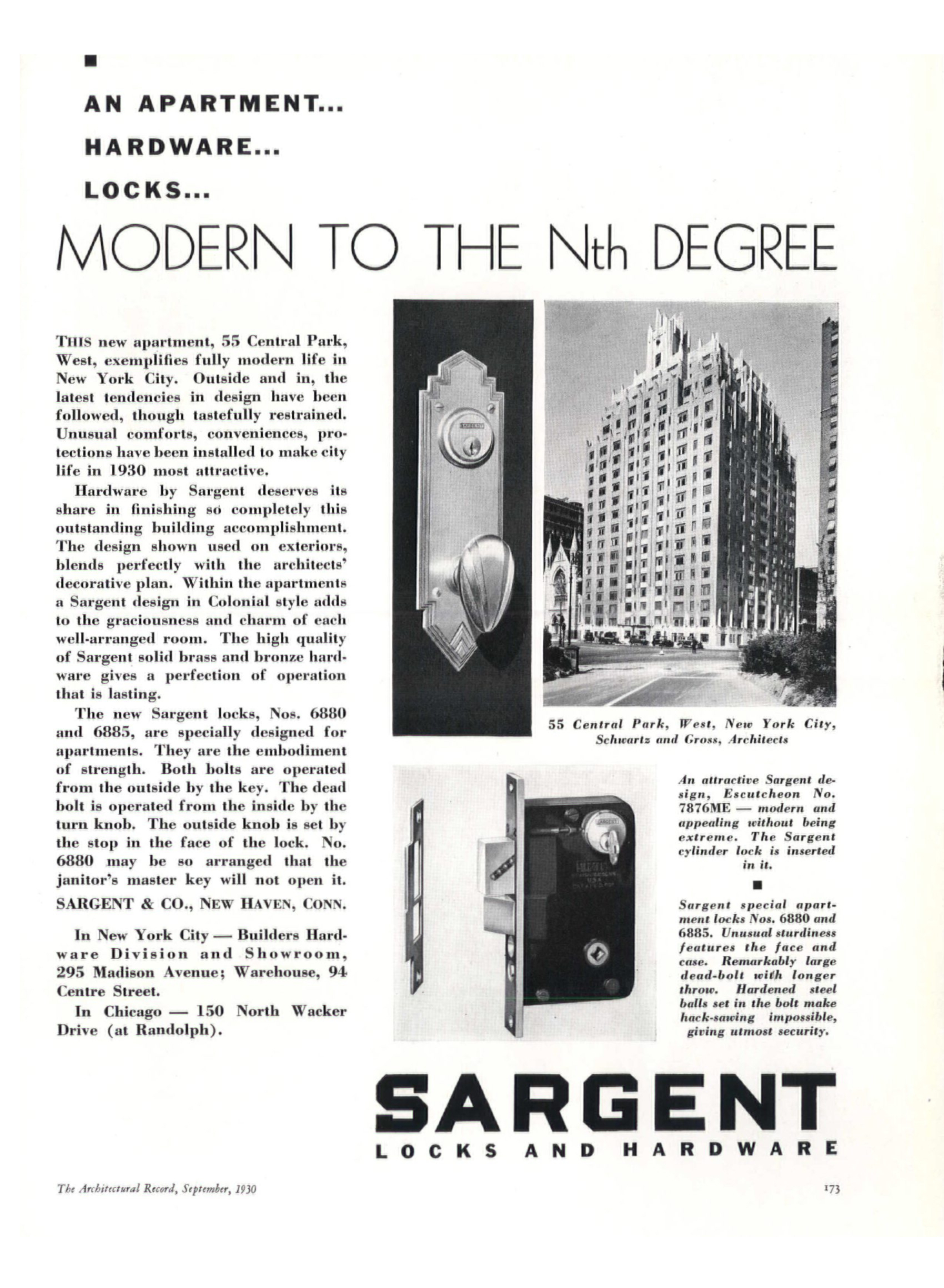

Among those was 55 Central Park West on the site of The Courtney and The Georgian Court. Its trendy Art Deco design came from the drafting rooms of Schwartz & Gross for the 55 Central Park West Corp., specially formed for the project by Victor Earle and John C. Calhoun.

Completed in the fall of 1930, the 19-story brick and stone structure epitomized the Jazz Age. The warm yellow stone of the base stair-stepped to four floors above the entrance at on the 66th Street side. The Oz-ready geometric piers that clung to the facade gave dimension and dynamism. The top-most floors detonated in a white mountainscape of spiky stepped finials and piers.

Upper West Side apartment buildings, unlike their East Side peers, were routinely given names–like The Dakota and The Ansonia. The new Central Park West buildings followed suit, including the San Remo and El Dorado. But Earle & Calhoun were content with the address, 55 Central Park West.

Months before its completion well-heeled tenants had lined up to sign leases. The building was 75 percent leased in July.

The wealth of its residents was evidenced the following year when Charles E. Douglas’s 65-foot yacht exploded in Gravesend Bay. On October 20, 1931, the captain of The Hat, Victor Belding, was filling one of the fuel tanks when the explosion occurred, destroying the vessel. Douglas placed its value at more than $800,000 in today’s dollars.

Living in an eight-room apartment on the 17th floor was Edward R. Brevoort and his wife, the former Mary Waldie. Like the wives of most moneyed businessmen, Mary spent her summers away from the city, being joined by her husband on the weekends and periodic longer stays.

Mary was on Cape Cod in the summer of 1932. The household staff was cut back to one maid during the summer months and she “slept out,” meaning she did not live with the couple. She was therefore not there at 6:00 on the morning of August 18 when doorman Stanley Dawson “was startled by the thud of a body in the rear courtyard,” according to police.

He discovered the body of the 60-year-old Brevoort in his pajamas, beside a window screen. The impact was powerful enough to wake other tenants. The suggestion of suicide at the time was something that was strenuously denied by upscale families. That may have led to investigators releasing an amazingly detailed conjecture of events preceding Brevoort’s death.

Police told reporters “His bed had been slept in. Walking through the apartment, he had apparently felt dizzy, stepped toward the window for air, and toppled out, carrying the screen with him.”

The year that 55 Central Park West was completed famous band leader and singer Rudy Vallee married the relatively unknown motion picture actress Fay Webb. The newlyweds moved into the new building.

On September 23, 1932, the upstate New York newspaper The Irvington Gazette reported: ”Barney’ Huston, of East Clinton Avenue, popular Rye patrolman, had the privilege last Friday night of ticketing Rudy Valee [sic], noted orchestra leader and crooner.” The officer had been sitting in his patrol car on the Boston Post Road when Vallee sped past him on the way home from Connecticut.

Like Rudy Vallee, Pons had a pet; but unlike his German shepherd, hers was far more exotic–a Brazilian jaguar named Ita.

“The orchestra leader was brought to Rye headquarters and posted at $15.00 bail for speeding at 45 miles.” Vallee gave his name as Hubert P. Vallee. He did not bother to show up at court the following Monday, forfeiting his $15. The newspaper clearly sided with Officer Huston. “Poor Rudy seems to have no end of trouble if it isn’t with his wife, it’s a cop, but in this instance with a good one who believes in doing his duty. Rudy or no Rudy.”

The trouble with his wife mentioned in the article referred to reports of marital discord that had hit the newspapers a month earlier. Only a year into their marriage, The New York Times reported on August 30, 1932, “a Reno divorce is likely unless difficulties that have arisen between them can be harmonized.”

Both the crooner and his wife were using attorney Hyman Bushel. He told reporters the “several court actions” brought against Vallee by Fay were caused by “a question of not getting on together” and a “wide divergent in temperament.” The Times article noted that Vallee was on tour and said, “Mrs. Vallee is staying at the Vallee apartment at 55 Central Park West with her father and mother.”

Fay Webb Vallee left New York, and in 1935, Vallee sued for divorce, contending that she was carrying on a dalliance with dancer Gary Leon. The courts sided with Vallee, giving Fay little compensation. She filed several appeals in California and New York to no avail.

Rudy Vallee’s name had appeared in newspapers for another legal matter in the spring of 1934. On April 2, a maid, Nora Sullivan, took Beauty, a black Pomeranian, for a walk in Central Park. She was one of 34 other women who were fined $1 each “for allowing their pets to roam unmuzzled.” Like Beauty, the other 33 dogs were Pomeranians. The women appeared in court and complained that “muzzles are not made for Pomeranians.”

The judge was not moved. According to The New York Times Magistrate Aurelio barked, “Get a muzzle anyway, even if you have to make it yourself.” The article pointed out that Beauty was “a dog owned by another Vallee servant, not the crooner’s shepherd, Windy.”

Vallee was not the only celebrity in the building at the time. Opera star Lily Pons was a resident during the 1930s, and Ginger Rogers took an apartment here at the same time while appearing on Broadway. Like Rudy Vallee, Pons had a pet; but unlike his German shepherd, hers was far more exotic–a Brazilian jaguar named Ita.

The diva had received the animal as a gift when it was just three months old. She treated it like a house cat, and Ita traveled with her in railroad cars and hotel rooms. Eventually, however, Pons was convinced to give Ita to the Bronx Zoo. The Times explained on March 16, 1934, “But Ita disliked visitors. She didn’t mind Miss Donna McKay, the singer’s secretary, or the French maid, because she grew up with them. Lately, however, she had begun to snarl at visitors and her restless tail gave danger signs.”

Ita rode to the zoo in the front seat of Pons’s limousine with the chauffeur. The singer and her jaguar had a sad parting and Pons was specific regarding the cat’s diet. She told keeper Max Lendsberry “Ita must be fed twice each day. She likes only raw meat, run through the chopper.”

Another high-profile resident was former broker Charles A. Stoneham. His colorful and sometimes shady career included ownership of the New York Giants baseball team and the New York Giants soccer team. By the time he and his wife, Johanna, moved into the building his name was still stained by two Federal indictments in 1923–one for perjury and the other for mail fraud–both of which he was cleared of. And his involvement in the “Soccer Wars” of 1929 which led to the disbanding of the American Soccer League also tainted his reputation among sports fans.

In the early 1930s Stoneham showed symptoms of Bright’s Disease, a kidney disorder better known today as nephritis. He went to Hot Springs, Arkansas in the winter of 1935-36 and died there on January 6.

Other residents were no doubt shocked when Harry H. Rein was arrested on November 18, 1937, charged with the theft of $119,000 in securities. The stock trader, whose office was at No. 70 Pine Street, was accused of forging signatures to liquidate bonds. Loudly protesting his innocence, Rein was released on $10,000 bail awaiting trial. And he quickly found another money-making scheme.

Renting a desk in another security trader’s office, he and securities dealer Clarence Woodruff Valentine and his office manager, Jack Sullivan, set up a betting operation. They gathered thousands of dollars in bets on the Roosevelt-Wilkie election. Then they disappeared. On November 4, 1940 investigators for the Federal Securities and Exchange Commission started a search for the men, who made off with $16,800 in winnings they owed to Roosevelt supporters.

In the meantime, Louis Baumgold had serious servant troubles. The wealthy jeweler was a partner in Baumgold Brothers, one of the leading diamond importing and cutting firms in the country. Two of the family’s live-in servants in 1937 were housemaid Josephine Kotva and chauffeur Joseph Gerschner.

On January 30, 1938, Baumgold called the police to report he had been burglarized. Missing was $9,500 in silverware, jewelry, and costly linens–a significant $165,000 haul today. The investigation into the case did not take especially long. On February 21 the 36-year-old chauffeur and the 30-year-old maid were arrested.

Interestingly, it was a jury member and not Gerschner’s brazen crime that drew press coverage. On May 14, 1938, the Indiana Recorder ran the headline “New York Has First Colored Woman Juror” and reported, “A decided advance in the struggle for equal rights was registered here this week when Mrs. Virginia G. Pope, a Negro housewife, was chosen as a juror in the Court of General Sessions.” It was the first time in the 225-year-old court history that a black woman had served.

When the nation was pulled into World War II with the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, resident Rae Simon threw herself full force into fundraising. And she did not allow her age to get in the way of her efforts. Three years later, on June 10, 1944, The Times reported, “An advance campaign for the Fifth War Loan begun by Mrs. Rae Simon, who is 77 years old, and one of the city’s most successful house-to-house canvassers in previous drives, already has resulted in the sale of $4,000 worth of war bonds.” So far, she has collected more than $250,000 in bond sales.

The article added that during the current drive, “Mrs. Simon plans to solicit every tenant in the apartment building in which she lives at 55 Central Park West.” But, of course, the well-mannered widow did not knock on doors indiscriminately. “She writes to all her prospects and arranges appointments before making her bond sales calls, she explains.”

The crafty Mrs. Simon started her appeal, telling each prospective donor, “Take your watch out. I promise not to stay more than three minutes, five at the most. If it is longer, you are detaining me.” One resident of the building purchased a $5,000 bond as a birthday present to her. Her largest single sale was $10,000.

She told a reporter that bond selling was a privilege for senior citizens “because we older people want to take a part in the war and this is one of the few ways in which we can serve and feel that we aren’t has-beens and really are accomplishing something.” Only a year later, Mrs. Simon had topped the $1 million mark in sales. In April, she embarked on what she called “Spring training” for the Seventh War Loan, in which she served as a “Blue Star Brigadier.”

Earlier that same year the owners of 55 Central Park West had commenced a conversion of about 26 apartments of the 115 apartments into “cooperative suites.” Prospective buyers paid around $381,00 for the spaces. But tenants sued, and a “controversial test case,” as described by The Times, dragged on for months. Finally, on September 2, the Office of Price Administration ruled. The newspaper said it “has forbidden the owners of the fashionable apartment building…to evict a group of tenants and convert their suites into cooperative units.” The ruling was based on OPA regulations that insisted to 80 percent of participants in any cooperative must be former tenants.”

The cooperative conversation eventually went through, with some existing residents purchasing immediately and other apartments converting as tenants moved out.

Klein made changes, one of which got him into hot water–both literally and figuratively.

When location scouts searched for a building to represent The Shandor, home of characters Dana Barrett and Louis Tully in the 1984 Ghostbusters, 55 Central Park West was a strong contender. And, although Don Shay, in his Making Ghostbusters, admits it was “our second choice,” it won out.

Also known in the film as “Spook Central,” it lacked the upper section called for in the script, so eight additional stories and the temple were added through matte paintings.

By then, well-known residents included Donna Karen, Marsha Mason, and screenwriter Ringgold “Ring” Lardner Jr. Composer Jerry Herman purchased a top-floor apartment in the 1970s and did major renovations, including removing walls. He brought in his Mason & Hamlin grand piano on which he had written the score to Mame. It would be the beginning of a somewhat bizarre period in the apartment’s history.

Calvin Klein visited Herman in 1983 and was reportedly so enamored with the apartment that he offered the composer $1 million at once. Herman told a journalist “It sounded like an offer I couldn’t refuse.” And he didn’t.

Like his predecessor, Klein made changes, one of which got him into hot water–both literally and figuratively. He installed a hot tub on the roof, which drew the ire of the co-op board. Then, in 1989 Klein put his beloved apartment on the market for $3.9 million. Motion picture producer Keith Barish signed a contract and a check for the $390,000 deposit, then changed his mind. Instead, Klein’s close friend David Geffen bought it for even more money, $4.3 million. He never moved in.

Almost unbelievably, he sold the space a year later for $4.6 to Keith Barish, who had changed his mind again. And equally unbelievably, Barish never moved in either. He purchased Marsha Mason’s apartment next door, thinking he would combine the two. But once again, he changed his mind and sold both to…yes…Calvin Klein.

Klein removed all but the load-bearing walls to create a Soho-esque loft space. The designer held on to the still gutted apartment until September 1998 when Diane Sawyer and her husband, Mike Nichols offered $7.5 million (plus another $1 million to the co-op board for the rooftop terrace rights). But they lost out.

Instead, another resident, Steve Gottlieb of TVT Records, outbid them. But fourteen years later, in 2012, the apartment was still vacant and Gottlieb had yet to finish renovations due to fights with the co-op board and the Landmarks Preservation Commission. He continued to live on the 18th floor and to use the penthouse for parties. Finally, after putting more than $5 million into “infrastructure improvements,” he placed it on the market in 2012 for $35 million.

Schwartz & Gross’s 55 Central Park West is a handsome link in the chain of snazzy Art Deco apartment buildings that line the park–buildings that defined America’s concept of wealthy New Yorkers’ lives in the Depression era.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE