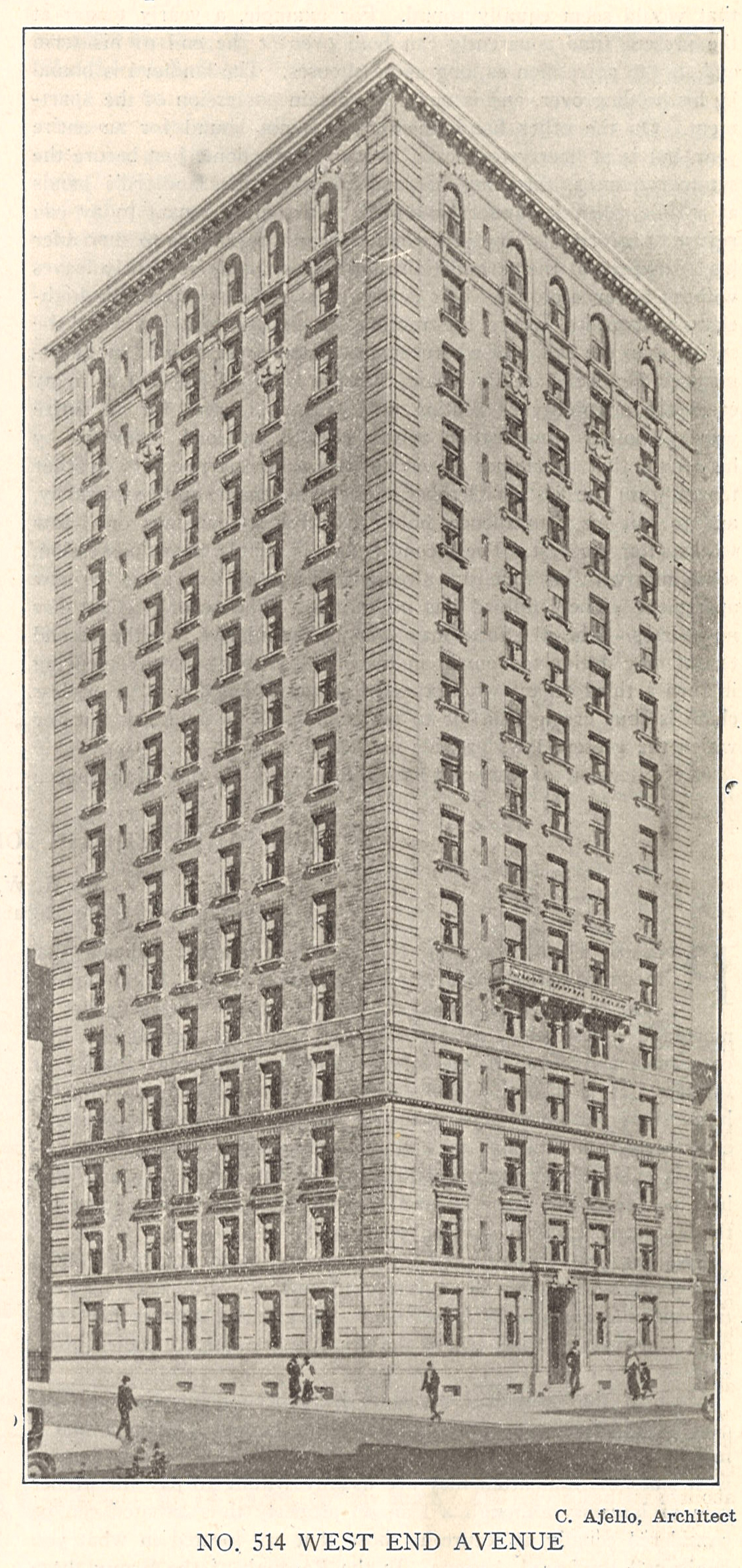

514 West End Avenue

by Megan Fitzpatrick

West End Avenue was the ideal location for a residential building in the 1920s due to its ‘beauty, quiet and accessibility’ according to the Real Estate Records and Builders Guide. With its tree-lined streets and grass plots, free from car lines, public transportation, and trucking, it was an obvious choice for Anthony A. Paterno to develop a 15-story apartment building at the corner of West End Avenue and 85th Street. This Renaissance Revival-style building was designed by Sicilian-born architect Gaetan Ajello and is characterized by its stone water table and one-story limestone base supporting the red brick structure with rusticated brick quoins that run from the second-story up. A series of intermediate stone cornices wrap around the facade with keystone arched windows and a denticulated stone cornice topping the elegant building. From the thoroughfare, one can spot the distinctive A.P., Paterno monogram above the entrance door.

In 1923, Anthony A. Paterno purchased a 4-story house from Edwin Baldwin at 514 West End Avenue and the adjoining 512 and 516, to develop his apartment building (New York Tribune, May 15 1923, p. 21). The Real Estate Record and Builders Guide featured an article in their November, 1923 edition on seven high-rise apartment buildings being constructed on the avenue titled “Unusual Building Activity Throughout West End Avenue ” in which they gave Paterno’s construction a highlight. The building, estimated at $751,875, was designed to contain 45 housekeeping apartments of four and five room apartments contained within them a foyer, living room, two bedrooms, bath with an extra bedroom possible in the five room apartments, nine servants’ rooms and three baths on the roof, as well as a storage room and laundry topped off with an abundance of light exposure owing to the location of the building along the avenue and street.

The Guide states the building was designed to ‘obtain the most space, convenience and comfort for tenants’ and this follows the trend of residential construction in the interwar period, where multi-family living was popularized among the wealthy families of the Upper West Side. The Paterno’s distinguished themselves as builders in NYC during the period of the 1920s apartment boom.

Joseph and Charles Paterno built their apartment building empire off the back of a project their father had begun, before his untimely passing, at 507 West 112th Street. They became Paterno Brothers Construction and built 30 apartment houses together before Charles broke away and formed Paterno Construction Company in 1910. Their younger brother, Anthony A. Paterno inherited the already well-established business and continued to build apartment houses primarily on the Upper West Side. Paterno buildings can be easily identified by the still visible, in many cases, monogrammed cartouches stamped by the builders – P, PB, JP, AP, or AC (“Paterno Family History”, Marabella Family, 22 March 2022).

The Guide states the building was designed to ‘obtain the most space, convenience and comfort for tenants’

The Paternos’ business of building apartments was profitable because of the transition of many wealthy families to apartment and apartment hotel living at the turn of the century. Previously, multi-family dwellings, or tenements, in the city were largely associated with the immigrant poor, of cramped and unsanitary conditions. However, trends changed in the late 19th century and the idea of the apartment house became fashionable, with the Real Estate Records and Builders Guide calling the apartment house ‘the tenements of the rich’ (Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale, 1995, p. 282). In this period, opinion towards apartment living shifted, mostly because they were seen as more profitable for developers to construct and single-family row houses were becoming infeasible due to construction costs. Additionally, the shift from single-family dwelling to apartments was becoming a necessity due to the rise in rents, and the suburbs were ‘out of the question’ for the fashionable middle-class members of society (p. 279-280). Apartments offered more space per occupant, generally a larger floor area, higher ceilings, greater security and required fewer servants, and so the districts of West End Avenue, Riverside Drive saw the demolition of many 4 and 5-story dwellings in favor of 12-15-story apartment buildings.

These types of apartment buildings characterized most of the development of the interwar period on West End Avenue with the majority of developers being Jewish and Italian families, who worked with a small group of Jewish and Italian architects (LPC Report, p.15). Gaeton Ajello, an Italian-born architect, was active in the construction of apartment buildings in New York, designing more than 30 apartment buildings in his near 20-year career. He worked with the Paterno and Campagna families for many of the major developments on the Upper West side including 514 West End Avenue but also Charles Paterno’s The Alamada, 255 West 84th Street.

By September 1924, newspapers across New York advertised rooms to rent at 514 West End Avenue. The early residents who rented rooms were made up of middle class families, most of whom were U.S born, with a significant population of Eastern and Central European immigrants mostly Russian, and German.

One of the earliest residents of 514 West End Avenue was Mr. Francis R. Stark. Stark was very accomplished as the general counsel for the Western Union Telegraph Company. He married Marie Louise in 1904 and the two moved onto the 15th floor of 514 West End Avenue as early as 1925. Tragedy struck the couple, and the neighborhood, on February 2nd 1931 when Marie Louise fell to her death from her 15th floor bedroom window to the sidewalk below.

A cab driver witnessed the horrifying sight early Sunday morning while cruising down West End Avenue, who then informed the police. Mrs. Stark had experienced poor health for several months leading up to her death including suffering a mental breakdown, which resulted in her needing a live-in nurse to care for her. Despite her being in good spirits before her death, both Mr. Stark and the nurse believed her death to be a suicide. She left behind no children at the age of 44 (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 02 Feb 1931, p. 17). The Brooklyn Daily Times reported that not so far away at 575 West End Avenue, Fred Unger, 59, was discovered dead shortly after Stark, by gas poisoning in his kitchen. Two deaths within a short period and distance on the Upper West Side (The Brooklyn Daily Times, 02 Feb 1931). Francis Stark died as a retired Vice President of the Western Union at the age of 79 at his home at 575 West End Avenue in 1956 (Daily News, 27 Nov 1959, p. 4).

Another of 514’s first residents were Charles H. Shulman, a Russian-born businessman and his daughter, Minna Shulman. Shulman was in the retail clothing business for 35 years and maintained several stores in Manhattan and was the president of the Manhattan Bridge Transit Improvement Association. One of his stores was located at 79 and 81 Bowery and was forced to close due to negative associations with the eclectic Bowery neighborhood. Many businesses struggled as customers and wealthy patrons dared not to enter the street and Shulman stated customers even refused to wear clothing labels with Bowery on them. Shulman and the Association proposed to rid the Bowery of its vices such as saloons filled with ‘undesirables’ and even change the name of the neighborhood to “Central Broadway ” for the sake of the businesses there. Thankfully, the Bowery maintained its name – instead of yet another Broadway (New York Times, 17 Mar 1916, p. 11).

In 1926, Shulman announced the engagement of his daughter, Minna, who was the president of the New York Council of Jewish Women at the time, to Lawrence Wiseman, a lawyer (The New York Sun, 25 Sept 1926, p. 15). Census records indicate that by 1940 Shulman had become unable to work and moved in with Minna and Lawrence and their daughter Carol, 12 and son Charles, 9. Shulman didn’t have to move too far away from 514 as his new home was just two blocks down to 490 West End Avenue.

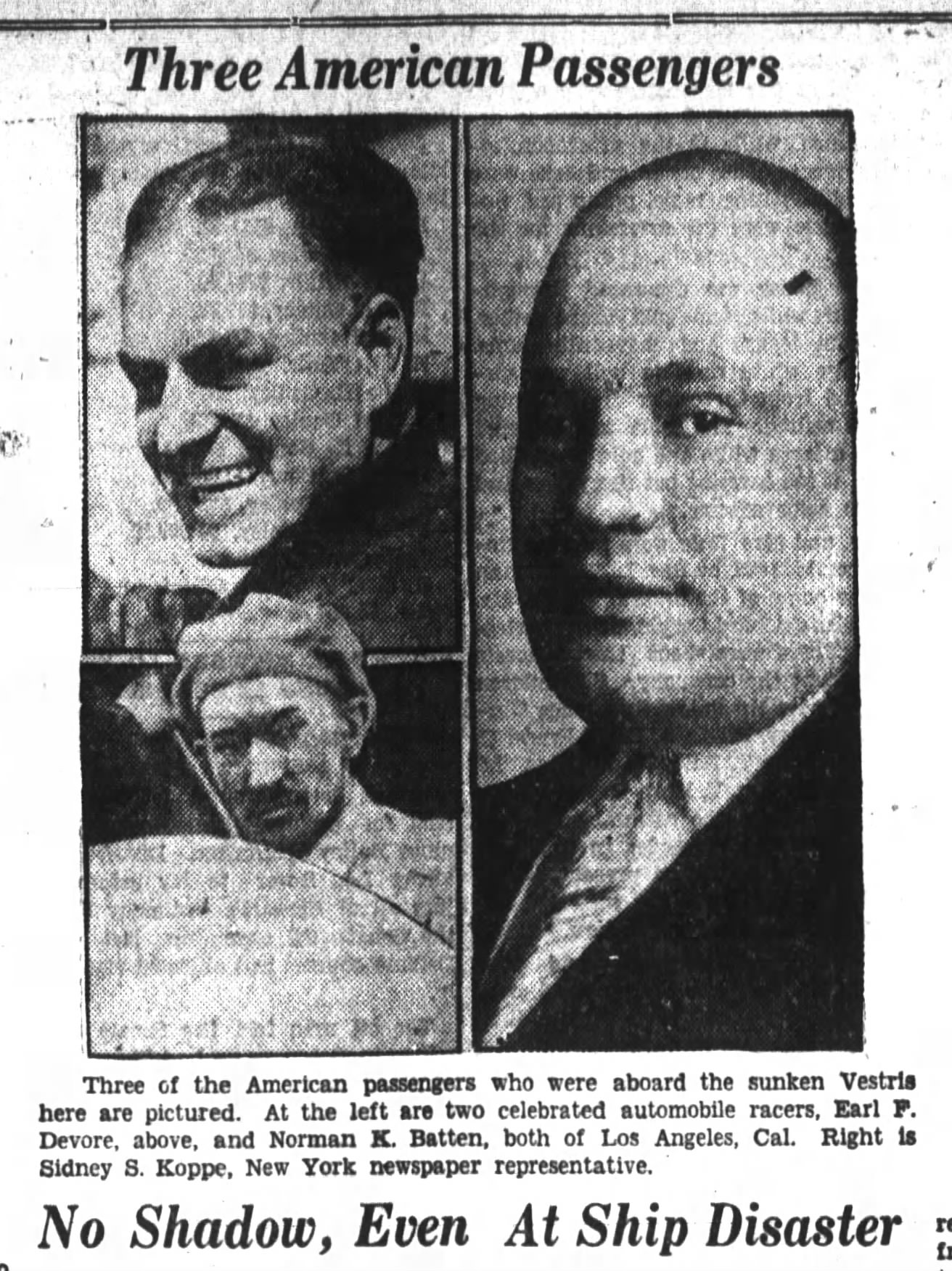

A devastating story is connected to another resident of 514 West End Avenue. Sidney S. Koppe was an advertising agent and president of S. S. Koppe, Inc., an advertising company headquartered in the Times Building. Through his company, he represented a number of South American publications and in 1928 he boarded the S. S. Vestris, traveling in first class to Buenos Aires for a conference with officials of the newspaper La Nacion, which he represented. The S. S. Vestris was making its voyage from New York to Barbados and Buenos Aires with 129 passengers and 197 crew on board, under the command of Captain William J. Carey.

Rollins moved into 514 West End Avenue at the beginning of his professional managerial career around 1954-55 when he found success with balladeer Harry Belafonte when he was a budding star

On the 12th of November 1928, just two days after leaving Brooklyn, Vestris called out a distress signal, 300 miles off the coast of Hampton Roads, Virginia. Heavy weather and failed water pumps had caused the starboard beam ends and deck to take on water around 10 A.M. and by 1:05 P.M. passengers were beginning to load onto lifeboats and some were rescued by boats answering the SOS. One of the last transmissions from the ship was to U.S. Battleship Wyoming in response to a two hour estimated time of arrival, stating ‘too long…going to abandon ship’ (The Brooklyn Daily Times, 13 Nov 1928 p. 70). Several rescue boats later arrived at the scene of the wreck and reported no sign of the ship or lifeboats. Koppe was tragically one of the 112 passengers and crew, including the captain, lost at sea. On the 15th November 1928, an obituary for Koppe was reported in the Yonkers Statesman (15 Nov 1928, p. 2).

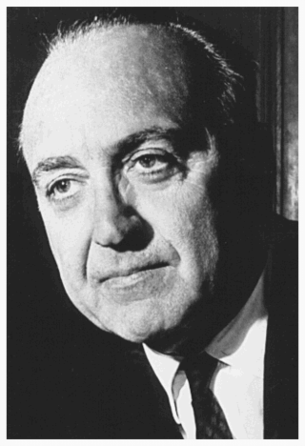

One of the building’s most intriguing residents has to be legendary film and television producer and talent manager, Jack Rollins. Rollins moved into 514 West End Avenue at the beginning of his professional managerial career around 1954-55 when he found success with balladeer Harry Belafonte when he was a budding star (The New York Age, 09 Jan 1954, p. 8). In December of 1954 it was reported that Rollins and Belafonte had ended their working relationship (Star-Gazette 29 Dec 1954, p. 14), which resulted in Rollins hitting Belafonte with a six figure lawsuit (Newsday, Suffolk, 21 Ap 1955, p. 82), claiming his psychiatrist, Janet Alterman Kennedy had brainwashed the singer into dropping Rollins as his agent and instead hiring her husband, broker and acclaimed author, Jay Richard Kennedy (Daily News, 28 Sept 1955, p. 656). He went on to drop the lawsuit shortly after.

Rollins found great success after Belafonte, representing TV acts that were on the rise in television in the 1950s such as the duo of Mike Nichols and Elaine May (Star-Gazette, 31 Jan 1958, p. 8), and rebel comedian Lenny Bruce. Rollins entered the world of film and television production when he met Woody Allen in the late 1950s. His first impression of Allen, despite his sheepish appearance at the door of his office, was that he believed he had the potential to be a triple threat, “like Orson Welles – writer, director, actor”. Alongside his long-time business partner Charles H. Joffe, he co-produced Allen’s feature film “Annie Hall” which garnered an Academy Award in 1977 for Best Picture. Rollins would continue to produce Allen’s films for over 20 years. He would later go on to consolidate his success as a master of his profession as the manager of comedy giants Billy Crystal, David Letterman, Martin Short and Robin Williams.

Rollins was a long-term resident at 514 West End Avenue having lived there for over 50 years with his wife, singer Jane Martin, and two daughters Hillary and Francesca, and had a home in upstate New York. He passed away in 2015 at the age of 100 (The New York Times, 18 Jun 2015).

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!