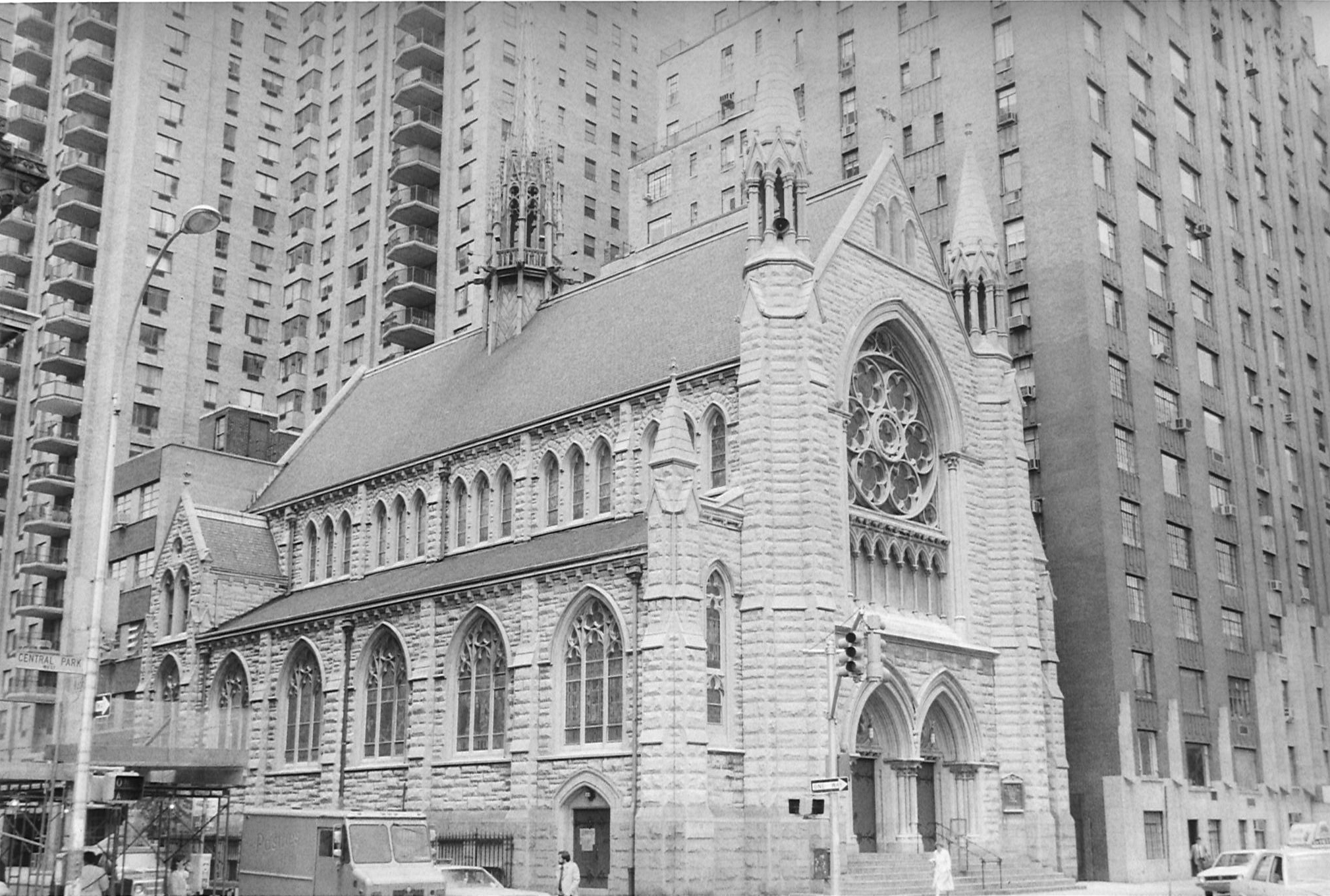

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church

by Tom Miller

The first Lutherans arrived in America around 1620, settling along the Hudson River. For two centuries they would be a religious minority in New York, overshadowed by, mostly, the Episcopalians. But by the middle of the 19th century, with the German population in New York quadrupled, the Lutherans were firmly established.

Among the handful of non-German speaking Lutheran churches was St. James. Founded in 1824, its first building was on Orange Street—a gift to the church from Pierre Lorillard. Later the congregation moved to a new church building on Second Avenue at 15th Street.

In the first years following the Civil War an irreparable rift occurred among the congregants. In 1868 a group splintered off, forming the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church on January 27. The new congregation purchased the former St. Paul’s Reformed Dutch Church at No. 47 West 21st Street for $60,000 where it would remain for more than three decades.

As the turn of the century neared, Holy Trinity sought both a new building and new location. At the corner of Central Park West and 65th Street stood the home of minister Rev. C. Armand Miller. The Lutheran minister’s wife, interestingly, was Vice President of the New York City Indian Association. The Association was formed that same year to “create and sustain a public sentiment…concerning the condition of the Indian tribes and the need of prompt action in their behalf.”

Before long the Millers’ house would be gone. In June 1902 Holy Trinity began construction of a new church edifice at No. 3 West 65th Street. The last services in the 21st Street church were held in February of that year. It was sold for $200,000 and while the new building was under construction, the congregation worshiped in the auditorium of the Young Men’s Christian Association on West 57th Street.

Schickel & Ditmars drew on 13th-century Gothic churches for inspiration. The Times compared it to Sainte-Chapelle in Paris…

The architectural firm of Schickel & Ditmars had been given the commission to design the new structure. Bavarian-born William Schickel and Isaac E. Ditmars were responsible for many of the buildings of the New York Roman Catholic Diocese, beginning in 1879 with the Church of St. Vincent Ferrer.

Completed two years later at a cost of $350,000, including the land (about $7 million in today’s dollars), the new Holy Trinity Lutheran pretended to be of stone construction. But, as The New York Times reported, “the structure is almost entirely of steel, including its two towers and steeple.”

Schickel & Ditmars drew on 13th-century Gothic churches for inspiration. The Times compared it to Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and although the comparison was rather grand, the central fleche and overall form shared the same pedigree.

Inside, Schickel used colorful stenciling and mosaics in the soaring sanctuary. The New York Times noted that “The roof is supported by graceful arches resting on columns of green marble.”

The church was consecrated on the afternoon of May 15, 1904, in the first of a four-day celebration. It was stressed to the press, however, that services would be “of the most simple character.” Appropriately, Rev. C. A. Miller delivered the first sermon in the new building that stood on the site of his former home. The Times reported on the over-flow crowd. “The church was crowded even to the organ loft with the 690 members, their friends, and well-wishers, and many who sought admission were turned away. Among those who had seats of honor were the eleven survivors of the eighty original members.”

Sunlight flooded through the windows, most of which awaited dedicatory stained glass. One of the first of these, installed in 1904, was The Second Coming of Christ window executed by Tiffany Studios. Over the next few years, magnificent stained glass windows would be installed one-by-one.

A year after the United States entered World War I, Rev. Charles J. Smith left for France as a member of the National Lutheran Commission for Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Welfare, New York. The New York Times reported that he “is pastor of one of the most influential Lutheran churches in New York City.”

The Lutheran churches of France had arranged to take care of the nearly 200,000 American Lutheran soldiers in France. “In essence it aims to bring the Church to the boys wherever they may be, not only to give them the comfort and encouragement of their faith, but to give them a welcome and make them feel at home on foreign soil.”

The purpose of Smith’s journey with the Commission was “by fellowship and counsel to hearten the Lutheran Church in France, and to assist this church both in ministering to its own people and to the United States soldiers, whom it may have opportunity to serve.”

One of those soldiers was Gerold Dieterlen. The young man never returned from the war, and his grief-filled mother commissioned a mosaic reredos behind the altar in his memory. The panel was designed and executed by Charles R. Lamb in conjunction with Talbot Hamlin of the Department of architecture at Columbia University. Reverend Dr. Smith gave the sermon at the dedication on January 9, 1927.

The memorial was in the form of a triptych with Christ in the center flanked by two angels symbolizing the church militant and the church triumphant. The exquisite work was called at the time “one of the most important contributions to the art of ecclesiastical mosaic of recent years.”

The young man never returned from the war, and his grief-filled mother commissioned a mosaic reredos behind the altar in his memory.

In a somewhat ironic twist, in May 1938, St. James Lutheran Church—from which Holy Trinity had spun off—was in serious financial trouble. On May 27, The New York Times reported that “The 111-year-old congregation of St. James Lutheran Church, the oldest of the denomination holding worship in English, will abandon its present edifice at the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and Seventy-third Street after 11 A.M. worship on Sunday, June 5.”

Unable to make its mortgage payments, the congregation voted to worship “temporarily” with Holy Trinity Lutheran Church. Newspapers reported that “St. James will keep its charter in the hope that it may someday establish a place of worship again on the East Side.” The friction of nearly a century earlier was forgotten, and the two congregations worshiped together once again.

After a process spanning four decades, the final of the eight stained glass windows was installed on June 1, 1941. The Last Supper window was dedicated to the memory of Carl Pickhardt, one of the original founders. Based on a painting by Zimmerman, the thirty-foot window was executed by Julius C. Koechig & Sons of French and English glass with French mineral colors.

In the 1950s, Charles Lamb Studios created six more mosaics to complete the 1927 reredos. The pastor at this time was Rev. Robert D. Hershey, who made Holy Trinity a household name nationally with his broadcasts of Sunday musical vespers, mostly by Bach. Hershey’s broadcasts would continue for several decades; and the Bach programs continue to the present.

As the neighborhood developed, Holy Trinity Lutheran Church became somewhat dwarfed. Yet Schickel & Ditmars’ classic 13th-century Gothic structure with its beautifully patinaed copper fleche is a welcomed oasis among the soaring apartment towers of Central Park West.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE