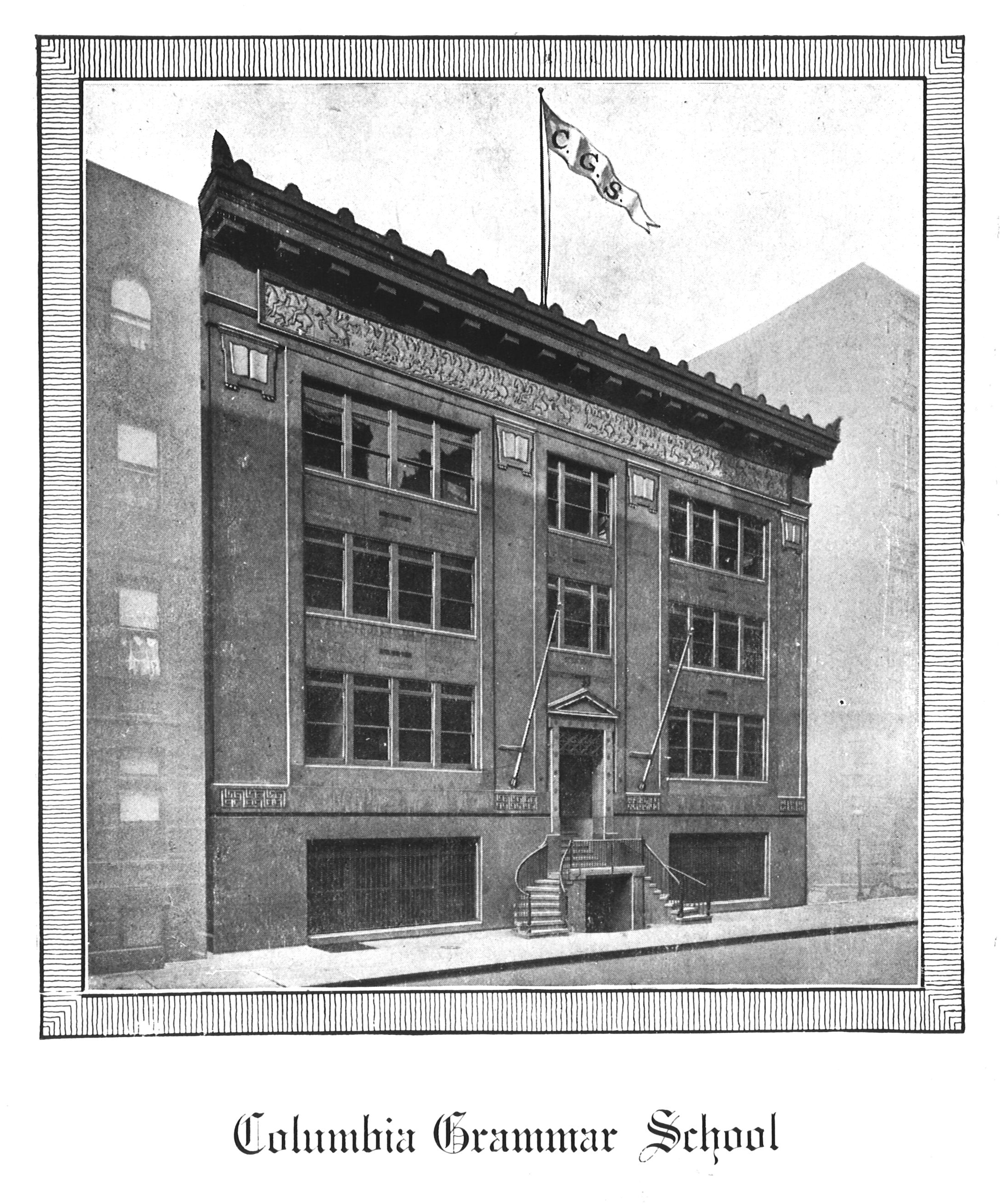

Columbia Grammar School

by Tom Miller

Originally called The Grammar School of King’s College, Columbia Grammar School was founded in 1764 to prepare boys for King’s College (today’s Columbia University). When the college changed its name following the Revolutionary War, the grammar school followed suit. The connection between the two institutions was severed in 1865.

Columbia Grammar School’s location on East 51st Street in Midtown had become intolerably hemmed in by commercial buildings by the first years of the 20th century. On March 30, 1907, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that the institution had purchased the 75-foot-wide plot on the north side of 93rd Street, just west of Central Park, “on which a three-story school and gymnasium will be erected.” There would be no danger of commercial buildings intruding on the site in a neighborhood rapidly filling with upscale rowhouses. The article noted, “Particulars can be obtained from Mr. Campbell, principal of the school.”

Filed on June 15, 1907, the plans now called for a four-story school to cost $45,000 (just over $1.25 million by 2022 standards). The New-York Tribune reported the structure would have “an original façade of brick trimmed with terra cotta and stucco work…The building will contain a two-story gymnasium.”

The plans reflected what must have been a deal-breaking stipulation in negotiations between Headmaster Benjamin H. Campbell and the potential architects. The architects of record were listed as “Beatty & Stone and Shiras Campbell.” Whether the established architectural firm was overly-eager to include Headmaster Campbell’s son in the project is questionable.

Construction began two days after the plans were filed and was completed with blinding speed. The school opened on October 8, 1907, just four months after ground was broken. Beatty & Stone seem to have been somewhat influenced by Lamb & Rich’s Berkeley School, completed in 1891. Like that private boys’ school, a dramatic split staircase rose to the main entrance, above the basement level. Strikingly similar was the classical frieze below the cornice, nearly an exact duplicate of that found on the Berkeley School façade, copied from a portion of the Parthenon.

“[They] set a record in the amount of Victory Bonds sold by secondary schools in New York City.” The combined primary and high schools raised $1,447,240 in bond sales.

Grouped windows allowed natural light to spill into the classrooms. The academic nature of the structure was reflected in plaques of open books that graced the top of each of the three-story piers between the openings.

On October 9, 1907 the New-York Tribune reported, “Columbia Grammar School, 93d street and Central Park West, reopened yesterday in its new fireproof brick and steel building, with a full attendance and a great influx of new pupils. This building was erected in one hundred and ten days.” An advertisement boasted, “gymnasium, laboratory, play ground, athletic field, preparation for all University Departments.” The under-performing sons of well-to-do fathers were not necessarily excluded. The advertisement noted, “Special courses arranged for boys failing at entrance examinations.”

As the advertisement mentioned, the school property included an athletic field–one that would not last for many more years. On May 12, 1908 The New York Times reported, “The Athletic Association of Columbia Grammar School held its twenty-seventh annual games on the school grounds, Central Park West and Ninety-third Street, yesterday afternoon, before a large attendance of the school and its friends and alumni.”

Benjamin Howell Campbell had been headmaster of the school since 1869. Described by The New York Times decades later as “a brilliant, crusty and tightfisted eccentric,” he was both scholarly and peculiar. With a fortune equal to $7.3 million today, he lived in an Elizabeth, New Jersey mansion but, “wore the same long coat and battered hat at school for years, but dressed every night for dinner by candlelight,” according to The New York Times in 1964. Campbell’s successor, Frederic Arlington Alden, recalled in his handwritten history of the school:

Every piece of string small or large was carefully rolled up for future use. In my five years under Mr. Campbell I cannot recall one cent of any kind spent for improvements…I was for three years the assistant headmaster, yet I was never allowed in the headmaster’s office…Nor was I permitted to enter the office of the secretary.

Benjamin Campbell’s devotion to his only child, Shiras, ended when the young man married without his approval. When Campbell’s will was read in 1925, he had left Shiras $1. By then the elder Campbell had been retired for six years. After serving the school for 51 years, he left with title Headmaster Emeritus.

In the meantime, despite Campbell’s unwillingness to spend money, the Columbia Grammar School offered surprisingly up-to-date amenities. On November 29, 1914, for instance, The Sun reported on the Junior Camera Club of Columbia Grammar School. “The club takes short trips to the surrounding towns and visits many places of interest. Last year many good photos were taken, including some in Washington D.C., and Mount Vernon.”

When the United States entered World War I on April 4, 1917, the students were too young to enlist. And so, they showed their support by other means. On April 22, The Sun wrote, “The wave of patriotic enthusiasm which has been sweeping over the whole country has deeply affected the boys of the Columbia Grammar School.” An assembly that included every student resulted in resolutions which were unanimously adopted. The three points included pledging “our undying loyalty to our country and its flat,” the hearty endorsement of “every act of our President and Congress,” and a pledge of “our aid, humble though it be, to help our country and its President in whatever way we can.” A copy of the resolutions was sent to President Woodrow Wilson.

In July 1920, perhaps not surprisingly a year after Benjamin Campbell retired, the school building was sold to the newly-formed 7 West Ninety-third Street Corporation. The New-York Tribune noted, “The school will be operated by the new owners, who formed the corporation to acquire title.” Among the new instructors was civics teacher Fiorello LaGuardia.

Another instructor, Dr. Charles E. Moore, had taught mathematics since 1875. A graduate of Trinity College, he had also studied medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and practiced medicine prior to accepting the position a Columbia Grammar School. Moore died at the age of 74 on September 21, 1922. After having served the school for nearly half a century, his funeral was held in the West 93rd Street building three days later.

A disturbing accident happened on March 5, 1925. Science instructor William C. Carl was conducting experiments in the laboratory when an explosion occurred, seriously burning the face and hands of 16-year-old Ralph M. Neustadtl. Six months later the boy’s father, Victor Neustadtl, sued Carl for $20,000 damages for Ralph and $1,000 for himself “for the loss of services of his son.” He alleged that Carl “failed to notify [Ralph] as to the inherent danger of an explosion if the chemicals were not properly mixed.” The injuries, according to the suit, caused “his face and right hand to be disfigured permanently and rendering the hand partially immobile.”

The building was erected in one hundred and ten days.

Almost simultaneously, the Alumni Association of Columbia Grammar School purchased the rowhouse directly behind the school at 22 West 94th Street “as a site for a memorial to the late Benjamin Howell Campbell,” as reported by The New York Times on September 20, 1925. The article noted, “The Campbell memorial will take the shape of a swimming pool, with a new gymnasium in the 60 by 75 yard…There will be a roof arranged for outdoor classes to accommodate the kindergarten and primary departments.”

The necessity for additional space was evident in the 1939 book by the Federal Writers’ Project, New York Learns. “It includes a coeducational kindergarten, and a primary school and high school for boys only,” it said, adding, “Columbia operates on an all-day plan, occupying the student’s time from 8:30 in the morning to 5:00 in the afternoon.” Tuition ran from $200 to $600 a year–a significant $11,000 today for Depression Era parents.

In 1944 World War once again was a focus of students’ attention. On December 28 The New York Sun reported, “Students of the Columbia Grammar School, 5 West 93d street, piled up one of the largest school returns of the country in the Sixth War Loan drive. They sold a total of $567,000 in bonds.”

The following year the boys out performed their previous sales. On December 31, 1945 The New York Sun reported, “The Columbia Grammar Schools, 5 West 93d street, have set a record in the amount of Victory Bonds sold by secondary schools in New York City.” The combined primary and high schools had raised $1,447,240 in bond sales.

In the 1950’s the once refined 93rd Street block had become seedy. Headmaster James Walter Stern told The New York Times reporter McCandlish Phillips in 1964, “Ten years ago we were taking a look at every piece of property that opened up on the East Side, but we found nothing to replace our existing facilities and we would have had a smaller school.” So instead, the school spread out into other properties along the block. In 1956 it added five brownstones, adjacent to the original building to the west, and in in 1997 and 2002 purchased two more. In 1984 a new structure was erected directly across the street that included classrooms, a library and gymnasium.

Renovations to 5-7 West 93rd Street in 1962 resulted in the loss of the split exterior staircase and the original main entrance. The alterations resulted in the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s snubbing the 1907 building when it mapped out the boundaries of the Central Park West Historic District in 1990, which included the 1984 building across the street, but gingerly cut out 5-7 West 93rd Street.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com