48 West 85th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Developer James A. Frame could be assured in his decision to hire the prolific architectural firm of Thom & Wilson, well-known in the early development of the Upper West Side/Central Park West district, to design a group of five, four-story rowhouse dwellings along West 85th Street. These followed a general pattern of constructing dwellings of three and four-stories on the quiet side streets of Central Park West, and Thoma & Wilson were leading the way throughout the later decades of the 19th-century.

On April 17, 1886 Arthur M. Thom & James W. Wilson filed plans for a stretch of four-story and basement brick, brownstone rowhouse dwellings from 48-56 West 85th Street in an ABABA pattern. These Queen Anne-style buildings, characterized by additional Neo-Grec elements, such as colonettes framing the upper two floors and angled bay windows, showcase a string of eye-catching, yet refined single-family homes. According to the Real Estate Record & Builder’s Guide, each of the 20×56 feet wide dwellings were built at a cost of $20,000 (17 April 1886A, p. 515). The first in the row of these elegant buildings is 48. Its design is typical of some of Thom & Wilson’s work, notably 25-33 West 88th Street. A highly inventive form of design, often seen in both the Riverside-West End and Central Park West Historic Districts, which incorporated not only a number of historic sources, but also an abundance of visual elements in the facade decoration. A variety of textures, shapes, and intricate carved work are utilized to adorn the buildings, to give them a unique and personalized look.

There are several examples of unique ornamentation on this rowhouse. Starting with its robust, dog-legged stoop, this landmark features some animal motifs including bird and lion face cartouches on the facade. Floral carvings can be seen beneath the angled bay window, most notably an acanthus motif as well as a figure of what appears to be a young girl on the first floor. Framing the doorway and window arches of the first floor are carved keystones and geometric shapes that appear as if they were carved wood. The most striking decorated elements are the oval cartouches which display different mirrored figures, also appearing at 52 and 56.

The symbolic meaning of the young girl, and the figures in the cartouches, is unknown, but they may possibly be a classical reference which would align with other classical motifs in this building’s design and indeed the architects’ body of work. Conversely, these figures might have a more personal meaning for the developer or architects. Either way, these cartouches and several other motifs, display that eccentric yet personalized approach utilized by Thom & Wilson.

A variety of textures, shapes, and intricate carved work are utilized to adorn the buildings, to give them a unique and personalized look.

James A. Frame’s ‘elegant new four-story cabinet-trimmed private dwellings’ were listed for sale 22 May 1887 (New York Tribune, 22 May 1887, p. 6), and the first residents of 48 were a socially prominent family in New York City. Selig Rosenbaum, a German-born merchant, who arrived in New York from the port of Bremen in 1878, married his wife Leonora in 1885 and the couple had a son, Harold. Rosenbaum had a fruitful career as the head of the large department store Rothenberg & Company, ‘a prosperous dry goods business at 34 West Fourteenth street’ (Times Union, 10 Oct 1899, p. 14). Rosenbaum, along with his business partner Leo A. Price continued to expand the business since its founding in 1899, including branching out into the ever-expanding merchant street on upper Broadway when they acquired the department store H. W. Schreiber & Co. at the intersection of Broadway and Ralph Avenue, in Brooklyn. By 1929, the company no longer existed, a possible effect of the hardships of the Great Depression.

Rosenbaum was well known as a wealthy member of New York society (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 02 May 1910, p. 5), having lived at both the Hotel Majestic, 115 Central Park West, and the Hotel Lombardy, 11 East 56th Street, when he retired, but most notably, he was a philanthropist. Upon his death on December 4, 1929, The New York Times published an article that detailed the 15 charities Rosenbaum had bequeathed in his will, totaling $27,000 (an estimated $479,000 today). The most notable of these included the Brooklyn Federation of Jewish Charities, the Brooklyn branch of the Ethical Culture School, of which Rosenbaum is cited to have been a founding member (The Brooklyn Citizen, 20 June 1935, p. 3), and the Tuskegee Institute (The New York Times, 15 Dec 1929).

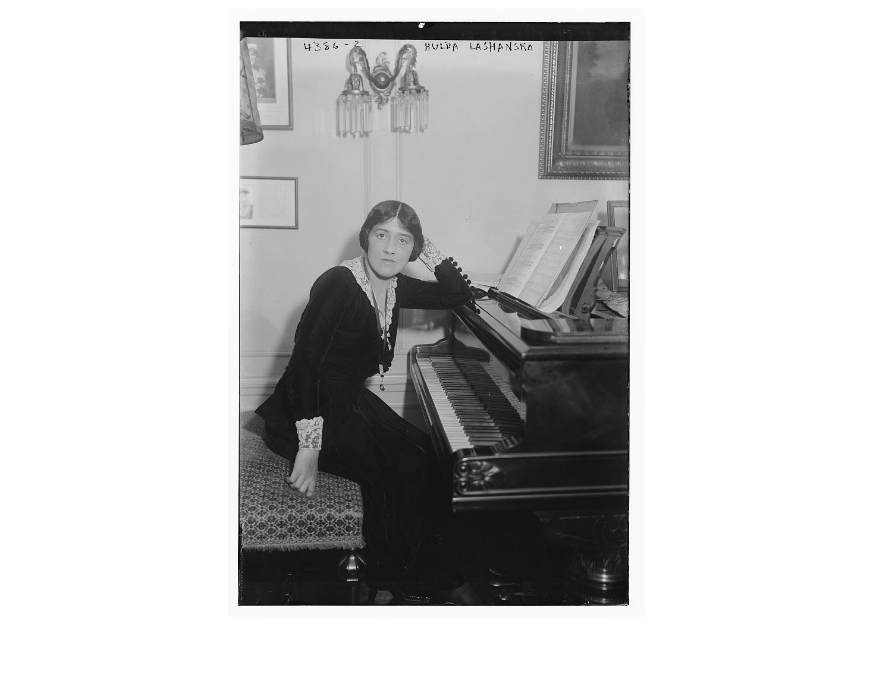

Rosenbaum’s son, Harold Rosenbaum, was a doctor specializing in children’s health (The Buffalo News, 22 Nov 1924, p. 26). Harold married Hulda Lashanska, an accomplished soprano singer, on March 28, 1913 at the St. Regis (The New York Times, 28 Mar 1913, p. 15). The couple took up residence at 48 West 85th Street sometime between 1920-1923, after his parents were no longer living there, and had two children, Leonore B. Rosenbaum and Margaret ‘Peggy’ Rosenbaum.

Following a successful recital at the Lyceum Theater, Hulda Lashanska became a pupil of Mme. Marcella Sembrich and launched her career as a soprano singer at the young age of 18. She took a respite from her singing after marrying Harold, but resumed in 1915, keeping her professional name of “Madame Lashanska”. Around 1918-19 she recorded exclusively for Columbia Records, and her record of “Annie Laurie” was particularly popular. Lashanska frequently sang with the New York Symphony Orchestra and her Sunday night concerts with the Metropolitan Opera in New York were a great success, establishing the singer as a household name. Lashanska also gave many concerts for charitable causes including a Gala in benefit of the ‘German Jews deprived of their livelihood and homes by the Hitler regime’ in 1933 (Daily Item, Port Chester, N.Y., 28 Aug 1933, p.7).

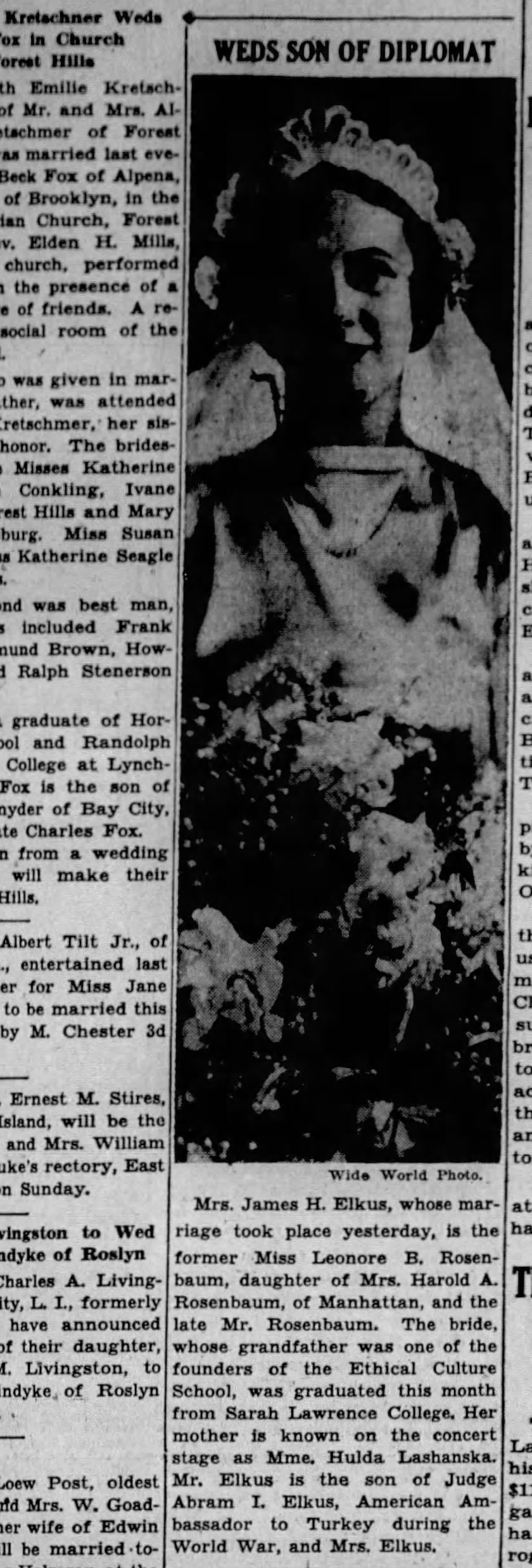

Tragically and unexpectedly, Harold Rosenbaum died in 1926 in Switzerland (Dunkirk Evening Observer, 08 Dec 1937, p. 9). Hulda and her daughters remained at 48 West 85th Street following his death but moved to 550 Park Avenue sometime after 1935 (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 08 Dec 1937, p. 6). Their daughters, no doubt well accomplished in their own right having grown up in an equally educated and artistic household, married into well-established families of New York City. A graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, Leonore B. Rosenbaum married James H. Elkus, a pilot turned steel firm executive, in 1935 at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel (The Herald Statesman, 07 Jun 1935, p. 17). Elkus was the son of Judge Abram I. Elkus, a US ambassador to Turkey during World War I, and their union was widely written about (The Brooklyn Citizen, 20 June 1935, p. 3).

Margaret ‘Peggy’ Rosenbaum, also a graduate of Sarah Lawrence, married the son of Governor Herbert H. Lehman, Peter G. Lehman in 1938. Gov. Lehman was actively involved in the US war effort in WWII having resigned as Governor to work closely with the State Department in the area of foreign relief and rehabilitation. Not long after he married Peggy, Peter Lehman enlisted as a fighter pilot for the American Air Corps, stationed in England. While working as Director General for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in March 1944, Gov. Lehman broke his leg while touring North Africa with British and French officials, forcing him to travel home without stopping in England to visit his son. Tragically, while operating a training exercise near Essex, Peter’s plane crashed. Upon his arrival to New York, Lehman learned of the tragic accident that led to Peter’s death (‘Life and Legacy of Herbert H. Lehman’ Columbia University Libraries).

Lashanska frequently sang with the New York Symphony Orchestra and her Sunday night concerts with the Metropolitan Opera in New York were a great success, establishing the singer as a household name.

Following her late husband’s unforeseen death, Peggy continued to surround herself with the world of music and married conductor and founder of the Orchestra of America, Richard K. Korn. Hulda Lashanska’s life and works were preserved when her daughters gathered correspondences, photographs, clippings, music and various papers into a collection and donated it to Sarah Lawrence College and is now safeguarded in the New York Library for the Performing Arts (‘Hulda Lashanksa papers’, New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts).

In 1950, the rowhouse was converted into a multi-family dwelling with three families residing there. The building, along with its siblings, preserves much of its original character from the exterior. Although the historic windows have been altered, the historic interior shutters can still be seen.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!