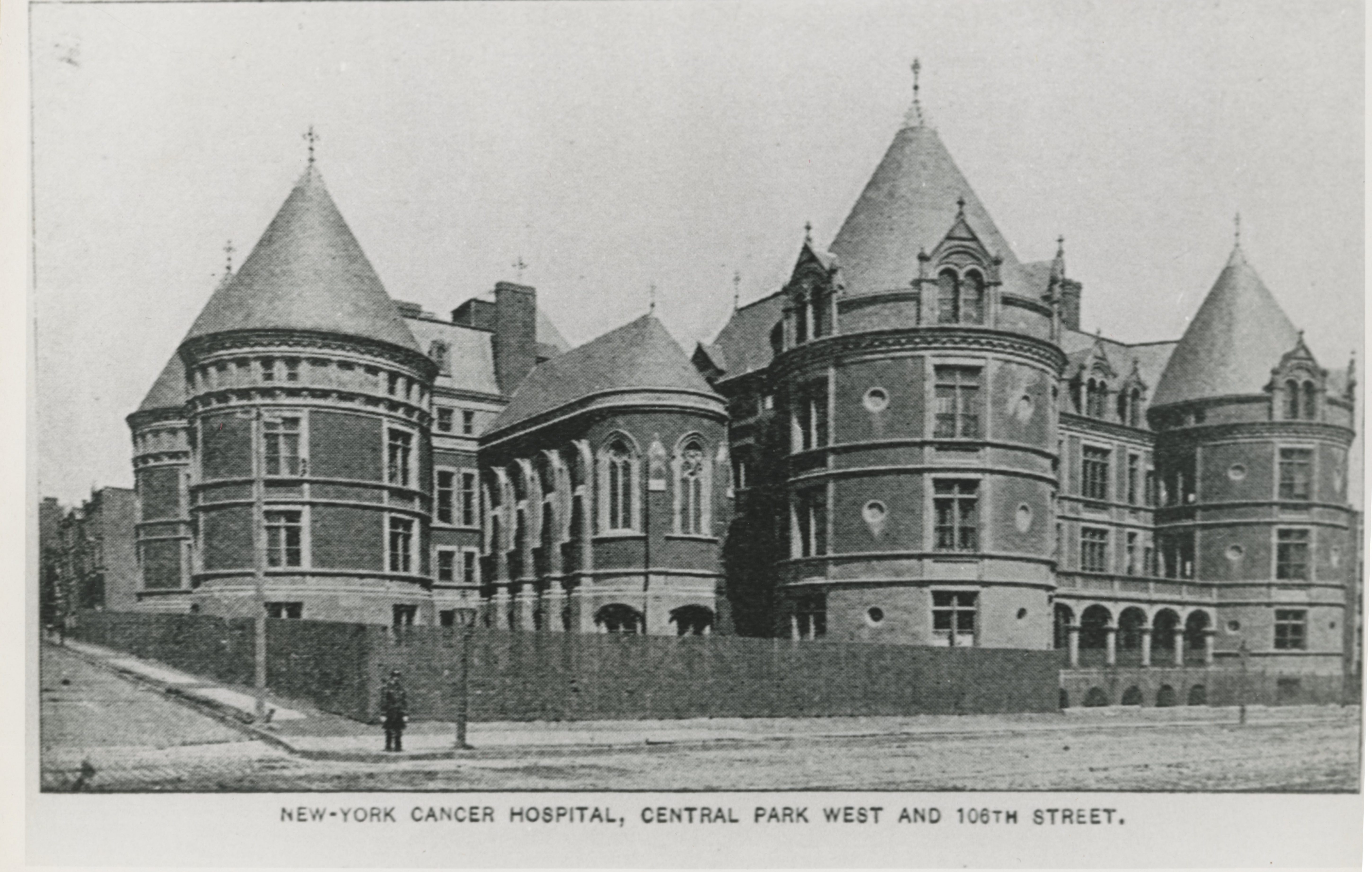

455 Central Park West – The New York Cancer Hospital

by Tom Miller

At the same time that Charlotte Augusta Astor, wife of John Jacob Astor III, was actively supporting cancer research and the care of victims of the then-incurable disease, Elizabeth Hamilton Cullum, the wife of Major-General George Washington Cullum, conceived of a hospital dedicated solely to the treatment of cancer.

In 1882, John Jacob Astor offered to erect a pavilion for the treatment of cancer patients at the Women’s Hospital. Astor’s generous offer was refused, so he turned to Elizabeth Cullum’s idea of a New York Cancer Hospital and in 1884, the project got off the ground. On May 17 The Record & Guide announced “The Cancer Hospital has taken title to the property on Eighth avenue [later Central Park West], recently purchased from Mr. Cohnfeld.” That property, engulfing the block front from 105th to 106th Street, came at a price of $80,000–about $2.15 million today.

Architect Charles Coolidge Haight filed plans in September. Construction costs were projected at the equivalent of just over $5 million today. Physicians provided him with guidelines on the most up-to-minute theories on hospital design.

Elizabeth Cullum would not live to see her vision completed. On September 15, the same month that the plans were filed, she died. When the details of her estate were released, The Syracuse Standard reported on November 20 “The late Mrs. Elizabeth H. Cullum’s will provides that her whole estate in New York City shall go to the New York Cancer Hospital.” Her West Coast property went to her husband.

On August 15, 1885 as the hospital rose, the Record & Guide commented, “This is of considerably more interest than all the buildings we have been talking about put together. The novelty of the design, the group of round towers that give the building its resemblance to a sixteenth century French chateau, is an outgrown of the plan, since in the diseases to the treatment of which this hospital is devoted it is especially desirable to avoid corners which prevent the thorough cleaning of rooms.” The physicians who had consulted with Haight had urged that corners, where germs may accumulate and grow, be avoided.

Before the main building was completed, Haight was called back to design a four-story “laundry and dormitory building” and a one-story “boiler-house.” The Record & Guide noted on January 2, 1886 “The laundry will contain accommodations for persons employed in that department.”

On September 15, the same month that the plans were filed, she died.

The formal opening of the first facility dedicated to the treatment of cancer in the United States (there was only one other in the world, that one in London) was held on December 6, 1887. The Evening World noted that “The building and grounds cost $350,000.” Of that amount, Astor had contributed $200,000 (more than $5.5 million in today’s money). In announcing the ceremonies, The Evening Telegram said, “Unfortunately Mrs. Astor is too ill to be present.” Ironically, she died of cancer six days later.

Even at the opening ceremonies, there was talk of expansion. The Sun reported that John E. Parsons, president of the board of trustees, said that “the present building is for women only, and the next to be built will be for men. A chapel will also be built.

Charles C. Haight had created an architectural tour de force. The Record & Guide said “The design belongs to the best period of French renaissance, such as greet the eye in the valley of the Loire distinguished by soft graceful lines, full of repose and calm beauty, and tourelles appropriate to the gentle undulations of the landscape.”

The ground floor held the office of the superintendent, reception rooms, staff offices and a temporary chapel. The Medical Record reported, “The main staircase is of bronze, with stone steps.” The second and third floors contained wards and private rooms. Each ward, located in the rounded towers, held eleven patients. Private rooms contained one or two beds. Haight put the operating theater and kitchen on the top floor–the first because of the better light, and the kitchen to keep the cooking smells and smoke away from the patients.

Ventilation in the wards was of utmost importance. “It has been found that the air of each ward can be changed completely with closed doors and windows every five minutes, and that, too, without producing annoying and dangerous draughts,” said The Times. Openings in the brick walls between the windows brought fresh air into the rooms. The “vitiated air” was sucked out through an iron column in the center of each ward by a fan in the cellar.

John Jacob Astor continued to give generously to the institution. Two years after the opening, on January 5, 1889, the Record & Guide reported that Charles C. Haight was again working on drawings, this time for an addition “which is to be known as the ‘Astor Pavilion,’ and also for a memorial chapel.” The cost would be paid “from a fund devoted to the purpose by Mr. Astor.”

Astor had provided another $145,000 for a men’s pavilion. The New-York Daily Tribune reminded readers “At present the hospital receives only women, having accommodations for seventy.” The new wing would double that capacity with these beds for men.

On May 2, 1890, The Otsego Farmer detailed the works of the facility. “The New York cancer hospital, as well known as the ‘Astor hospital,’ because of the liberal foundations given it by that family, counts among its patrons the very elect of New York’s best families…The number of patients treated in 1889 was 273; and an average of 40 days was devoted to each patient.” Of those 106 cases were “cured,” 71 “improved,” 82 unimproved, 42 died and 18 were still undergoing treatment.

Patients paid $7 to $20 week while they were hospitalized–the most expensive equaling about $580 today. The article pointed out that “This is remitted where the patient is unable to pay.”

The men’s pavilion was completed first. The Chapel of St. Elizabeth of Hungary named as a memorial to Elizabeth Hamilton Cullum, was dedicated on November 27, 1892. The Sun reported, “The prevailing tone of decoration is gold bronze, which contrasts admirably with the oaken work and the stone.

In May 1899, the New York legislature changed the name of the institution to General Memorial Hospital for Treatment of Cancer and Allied Diseases. The name change most likely had to do with the broadened caseload. Two months later the Architectural Record noted that it “was projected as a cancer hospital, though it is now used only in part, if at all, for that purpose.”

A horrifying accident occurred here early in 1903. Madeline Calder was being prepared for an operation by nurse Helen Smith who rubbed her body with a mixture of alcohol and ether. The Evening World reported, “The nurse, it is alleged, disobeyed one of the rules of the hospital in using a lighted candle, instead of performing her duties by the aid of the electric light.”

The candle sat within a small glass and, rather foolishly, Helen placed it on the bed as she worked. “It upset and set fire to the bedclothes. Mrs. Calder endeavored to throw herself out of the blazing bed, but it was too late, and she died a short time afterwards, after suffering excruciating agony.” Madeline’s husband, John H. Calder, sued General Memorial Hospital for the equivalent of $3 million in today’s dollars.

“The nurse, it is alleged, disobeyed one of the rules of the hospital in using a lighted candle, instead of performing her duties by the aid of the electric light.”

Despite the incident, the General Memorial Hospital continued to treat some of the wealthiest and most prominent New Yorkers. Among them were August Belmont, who received an appendicitis operation in February 1909; Herbert L. Satterlee, son-in-law of J. Pierpont Morgan in 1912; and Mrs. August Belmont (who, like her husband, also had an appendicitis operation) in 1915.

The hospital underwent two name changes before moving out of the old building permanently in 1955 as Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital. Shortly thereafter Bernard Bergman purchased the structure, converting it to Towers Nursing Home. Bergman managed the home with scandalous disregard for the patients or their conditions. Residents complained of no heat, vermin infestations, neglect, filth and odors, and physical abuse.

The wards, created with no corners to preclude the accumulation of dirt, were soiled and sickening. Prompted by numerous grievances, state and federal authorities initiated an investigation. Towers Nursing Home was closed in 1974. Only when the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission gave the building landmark status was demolition prevented.

Haight’s remarkable French Renaissance chateau sat empty and neglected for twenty-six years. Vandals broke in. Rain poured through the windows and roof. It became Central Park West’s version of a haunted house. Ailanthus trees grew from the turrets

In 2001 Chicago developers MCL Companies purchased the structure. Architects Rothzeid Kaiserman Thomson & Bee had been working on various proposals for the renovation of 455 Central Park West for almost 20 years. Now the two firms began working together to bring the building back to life.

The extent of the decay was far worse than almost anyone had imagined. The interior was essentially gutted. Everything other than the exterior walls had to be replaced. Using historic photographs, Rothzeid Kaiserman Thomson & Bee removed mid-20th century additions, replicated details that could not be saved, and used salvaged elements to restore the main structure.

In 2004, the renovated building was complete. The historic hospital consists, now, of luxury apartments–even in the neo-Gothic style chapel–connected to a 22-story tower. The renovation earned no fewer than six awards from preservation and engineering organizations.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

Landmarks Timeline

BUILDING DATABASE

Designation Report