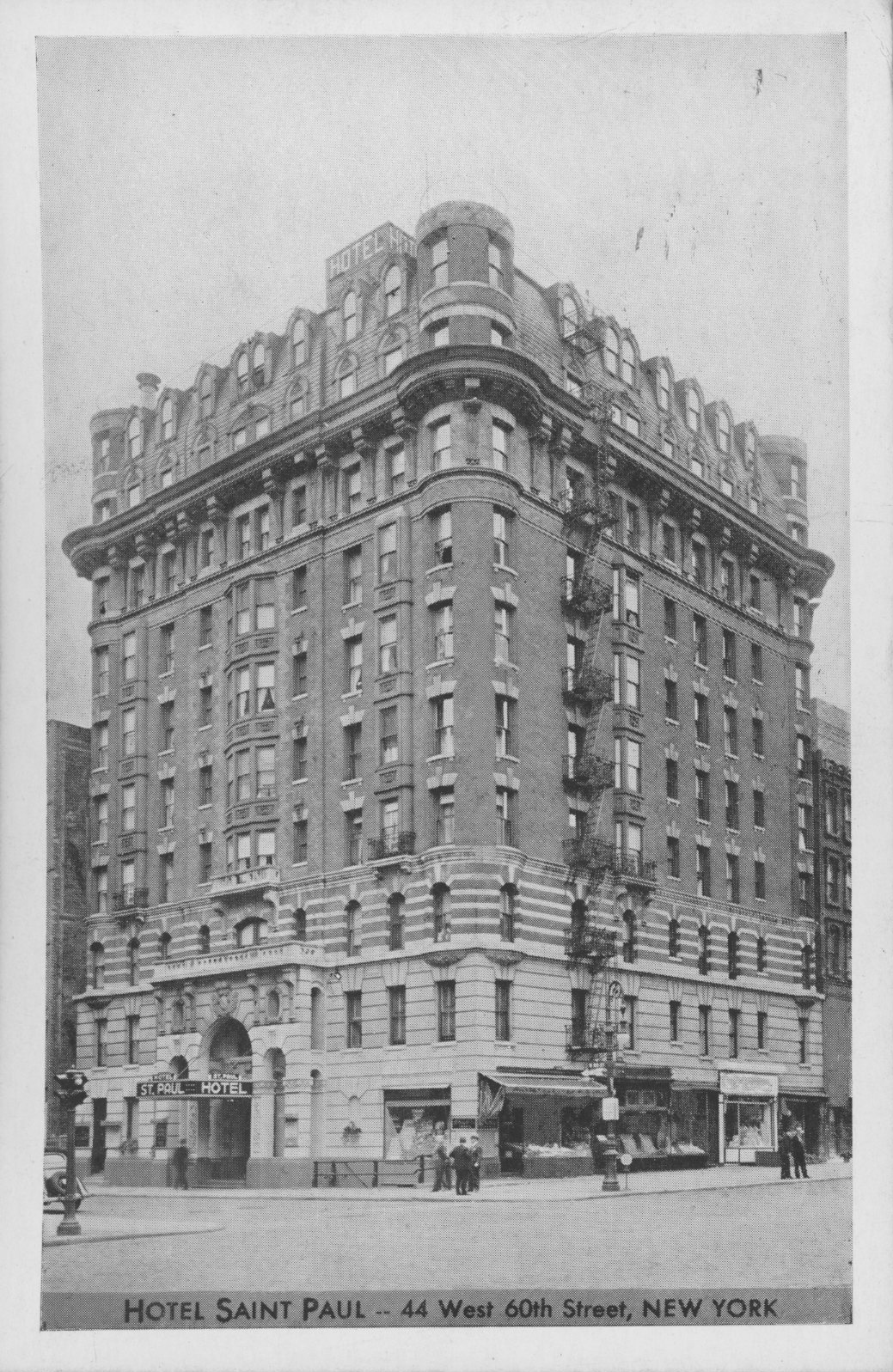

The St. Paul Hotel — 44 West 60th Street

by Tom Miller

By the end of the 19th century, Harry Chaffee had erected apartment buildings throughout Manhattan. In the fall of 1899, he began another. In October, architect J. J. Campbell filed plans for a seven-story “brick and stone flat” at the southeast corner of Columbus Avenue and West 60th Street. The projected construction cost was $101,000 (about $3.83 million in 2025 terms).

Completed the following year, the St. Paul Hotel was a medley of styles. The entrance on 60th Street sat within a large arch. The two-story base was clad in limestone, and the six-story midsection in red brick. The top section, above a prominent cornice, took the form of a two-story mansard, ornamented with gables, dormers, and corner towers.

The St. Paul Hotel was a “residential hotel,” accepting both transient and permanent guests. Those who were “stopping” in 1904 would pay $1 per day for a single room, $1.50 for a room and bath, and $2 to $3.50 for a suite. Because residential hotel suites did not have kitchens, tenants could take their meals in a downstairs restaurant. An advertisement in The Sun on March 20, 1904, described the St. Paul as “strictly first-class.”

Among the first transient guests were Floradora dancer Nan Patterson, and her sister and brother-in-law. Nan Patterson’s husband remained in Washington D.C. Nan became involved in a love affair with bookmaker Francis Thomas “Caesar” Young, who also was married.

On June 4, 1904, the couple was in a hansom cab. During the ride, reportedly, Young informed his 21-year-old mistress that the affair was over. At around 8:30 a.m., the cabbie heard a gunshot. When he stopped the cab, Young was found slumped over Nan’s lap, shot dead. “Oh, Caesar, Caesar, what have you done?” Nan was crying.

The firearm, discovered in the dead man’s pocket, was found to have been purchased in a pawnshop by Nan. (The Evening World remarked, “It was right after the locating of the pawnbroker who sold the revolver that J. Morgan Smith and his wife, brother-in-law, and sister of Nan Patterson, disappeared from the St. Paul Hotel.”)

Nan Patterson was one of several occupants of the St. Paul Hotel who saw the inside of a courtroom that year.

Nan insisted that Young had committed suicide. Police doubted that the dead man had placed the gun back into his pocket, and she was arrested. Her trial started on November 15, 1904, but ended in a hung jury. The second trial, begun on December 5, had the same results. Nan Patterson’s third trial commenced on April 18, 1905. Three weeks later, on May 4, the New-York Tribune reported:

Scenes of unusual excitement marked the closing hours of Miss Patterson’s trial. Not only was the courtroom in which Recorder Goff delivered the charge to the jury packed to its utmost capacity by persons who seemed to have an almost fanatical eagerness to observe the woman on trial for her life, but a crowd of a few thousand persons kept watch outside of the Criminal Courts Building.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, Nan’s different accounts of what happened, and what the prosecutors called her “silly story,” this jury, too, was unable to reach a verdict. District Attorney James T. Jerome said he would not bring the case to trial again, and Nan Patterson was set free. On May 3, 1905, The Evening World reported, “She said that she would go direct from the courthouse to the Hotel St. Paul at Sixtieth street and Columbus avenue and remain there until time to take the 5.10 train to Washington.”

Nan Patterson was one of several occupants of the St. Paul Hotel who saw the inside of a courtroom that year. In May 1905, stenographer William Brady went to a most unlikely place to gamble—the horse betting operation set up by Police Captain Bourke in the Mercer Street Station. Brady made a complaint to headquarters that “he lost a lot of money in the place.” Before Commissioner William McAdoo sent a raiding party to the precinct, Brady forewarned him, “the place was a fortress.”

McAdoo’s men arrived with “axes, sledgehammers, crowbars and jimmies,” reported The Sun on May 15. After a battle with Bourne’s men, they gained admittance to find a fully outfitted gambling parlor in the basement. Brady testified in the prosecution’s case.

The following month, on July 14, Arthur E. Alexander, who lived here with his wife, was arrested. Alexander was the former secretary of John Barrett, United States Minister to Venezuela. Barrett accused him of “stealing a typewriter and with forging his name to two checks.” The checks would total the equivalent of just over $4,000 today. One of them, reported The Sun, was “cashed at the Hotel St. Paul.”

Sarah Davidson was the wife of Harry C. Davidson, the president of the Savoy Shirt Company. In 1912, the couple lived at the Hotel Narragansett. In March, Davidson accompanied a private detective to the St. Paul Hotel and barged into the apartment of a man named Schultz. There they discovered Sarah and the man in an uncompromising situation. The Sun reported, “she said to her husband, ‘Well, you have finally got me.’”

It was around this time that the St. Paul Hotel began attracting musicians and thespians. Professional organist William Christopher O’Hare moved in around 1915. By the end of World War I, actors George and Catherine Giddens lived here.

George was born in England in 1845 and first appeared on stage at the age of 15. By now, he was a well-known character actor and, according to The New York Times, “considered one of the foremost low comedians of the English-speaking stage.” Catherine, who was known on stage as Catherine Drew, was born in Virginia. She and George formerly toured in South Africa and Australia with a sketch, “Are You a Mason.” The couple had relocated to New York City in 1911.

Catherine Giddens died in the couple’s apartment here on May 8, 1919. George remained here, continuing to act until, while appearing in Happy-Go-Lucky at the Booth Theatre, his health began to decline. He died in the apartment on November 21, 1920.

Vera Maynard had just turned 30 years old on September 5, 1922. The young widow aspired to be a film star and lived in the St. Paul Hotel. Her efforts to break into motion pictures were not working out, however. That day, two men passed her on the street and “saw the woman drink something from a bottle,” reported the New York Herald. Suspicious, they alerted authorities, and she was transferred to Harlem Hospital, where she died from poison. A neighbor at the St. Paul Hotel told a reporter from the New York Herald, “the disappointed actress had made a previous attempt to take her own life.”

British-born actor Kevitt Manton was down on his luck when he moved into the St. Paul Hotel in 1931.

Resident Albert S. Angeles got an unexpected reprieve on August 7, 1924, when he appeared in Traffic Court for speeding. The New York Evening Post reported, “Angeles pleaded guilty, admitting he was driving an automobile at twenty-six miles an hour in Broadway.” Magistrate Cobb, like all Americans, vividly recalled the recent war and asked Angeles if he had served. The article said that his record as, “a chauffeur for General Pershing in France during the World War and that he also was a veteran of the Spanish American War brought him a suspended sentence.”

Wilhelm Schaffer, listed his profession as, “conductor, coach, composer, orchestrations” in 1924. He added to his ad in Musical Advance, “Available for Concert and Opera.”

An advertisement in theatrical newspaper The Billboard on February 18, 1928, marketed the Hotel St. Paul as “catering to the profession.” The room rate was $14 per week for a room and bath, and a “room with running water” (i.e., just a sink) was $10.50.

British-born actor Kevitt Manton was down on his luck when he moved into the St. Paul Hotel in 1931. He arrived in America in 1905. His most memorable role was in the 1922 play The Wheel of Life. Then things took a downturn. In 1925, his wife sued for divorce, accusing him of having an affair with actress Marjorie Rambeau. On July 31, 1931, The Brooklyn Daily Times said he and his girlfriend, showgirl Opal Essent, “had been unemployed for months and shared food money.” Manton and Essent were scheduled to meet on July 24, but she did not show up. The Brooklyn Daily Times reported, “Kevitt Manton, actor, who took an overdose of veronal when his meager funds gave out, and a showgirl friend failed to keep a date with him, died in Roosevelt Hospital Manhattan, last night.” A note in his St. Paul Hotel room addressed to Opal Essent said, “he was tired of life and accused her of failing him when he needed her most,” said the article.

The St. Paul Hotel stumbled along for two more decades. In 1955, clearance of the San Juan Hill neighborhood began as part of the 18-block urban renewal Lincoln Square Renewal Project. Among the first to go was the St. Paul Hotel (along with all the buildings from 58th Street to 60th Street and Columbus Avenue to Broadway. Two 14-story apartment buildings replaced the Columbus Avenue blockfront.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com