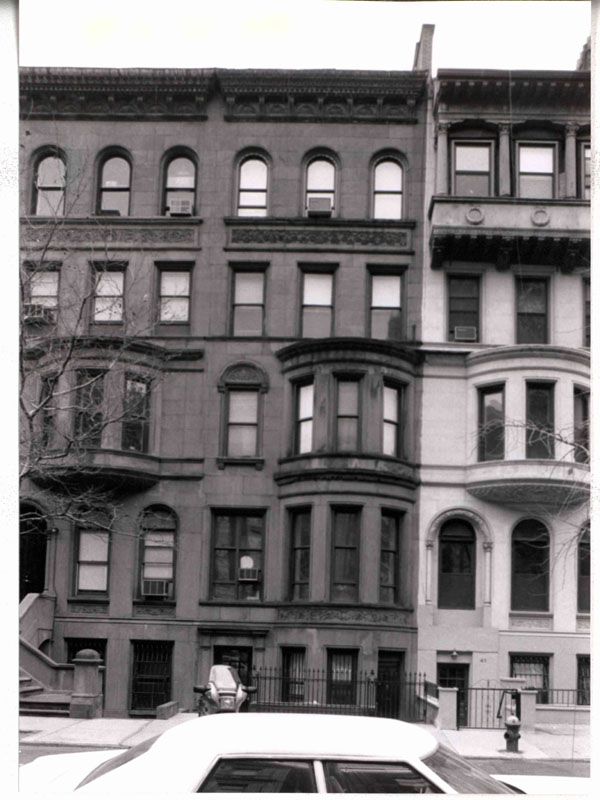

43 West 74th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Predating Percy Griffin’s row of elegant and modern townhouses on West 74th Street between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue stood architect Max Hensel’s row of five, five-story stone-faced dwellings. Commissioned by developer W. H. Jacobs in 1889, the 20-foot-wide brownstones were arranged in the ABABA style (Real Estate Record & Guide, 1889A, p. 300). 43 West 74th is the second in the row. The house lost its box stoop at some point, pictured without a stoop in the 1940s tax photo. It’s the only building in the row with a basement entrance (NYC Municipal Archives).

The Neo-Renaissance-style rowhouse’s most dominant features are its fenestration, with a mix of arches and rectangular punched windows, and most notably the double, three-window rounded bay. Before the stoop was removed, the building would have most likely resembled its siblings, featuring a box stoop and arched doorway flanked by colonettes and foliate carvings. Decorative carved bands stretch across the base of the ground floor bay window and the fourth floor.

Little is known of the architect Max Hensel, however, the German-born architect was busy designing Upper West Side buildings in the late 19th century. His architectural practice was established in New York by 1887, and he designed several buildings for the developer M. Giblin, notably tenements. Hensel would eventually leave his private practice and work for the Government as a foreman in the Office of Supervising Architect, overseeing Federal projects in New York.

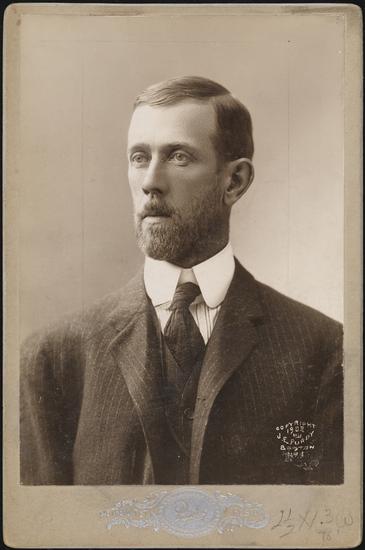

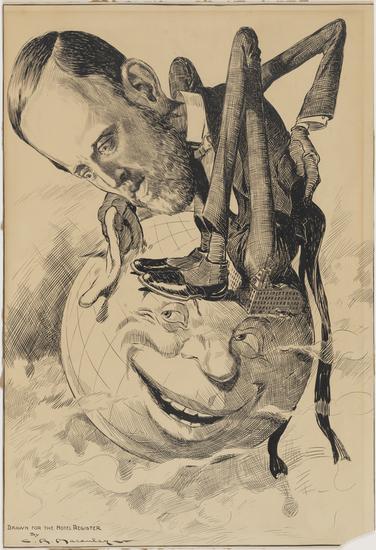

43 West 74th Street was bought by Simeon and Julia E. Ford when it went to market in 1890. Simeon Ford was a hotel proprietor widely known as a humorist for his after-dinner speeches. He found himself in the hotel business through his marriage, in his own words he was “yanked into the hotel business from the top. I married the proprietor’s daughter” (New York Times, Feb. 11, 1945, p. 38).

James E. and Julia A. Shaw were not in the hotel business. Julia was an artist, and James a silk merchant, but they bought land in a prime location that would soon become the Grand Union Hotel, conveniently beside the Grand Central Depot. They had passed on the management of the hotel to their children, Samuel T. Shaw, Julia E. Ford, and son-in-law Simeon Ford (New York Times, Nov. 23, 1901). The Grand Union underwent many additions as the railroads expanded and by 1901 it was one of the largest hotels in New York City.

He found himself in the hotel business through his marriage, in his own words he was “yanked into the hotel business from the top. I married the proprietor’s daughter”

Simeon, Julia, and Samuel would not only be business partners for over thirty years, but they would also be neighbors. Samuel’s mother owned the house next door at 41 West 74th Street and upon her death, she bequeathed it, and her farmhouse at Peekskill, to her son. Samuel T. Shaw followed in his mother’s footsteps and became interested in the arts, mostly as an avid collector.

Simeon Ford was an unusual figure in New York society. Tall and “thin as a rake”, he was often described as quiet and melancholy looking, until his talent for humorous speeches was uncovered. He would often make after-dinner speeches until he formally gave it up in 1910, saying they led him to become more of a public figure than he wished. Much like another humorist, Mark Twain, Ford once had to deny that he had died, and even wrote his own epitaph: “Here lies Simeon Ford, a poor hotelkeeper. But weep not, gentle stranger, lying comes easy to a hotelkeeper. On such and such date he bit the dust – the first decent bite he’s had in years” (New York Times, Aug. 31, 1933, p. 17).

After 45 years of managing the hotel, Ford’s Grand Union closed, largely due to the expansion of the subway and the new Grand Central Station. Ford would die suddenly of a heart attack in 1933 (New York Times, Aug. 31, 1933, p. 17).

Ford’s wife Julia led an interesting life as a philanthropist, author, art collector, and patron. She presided over a gallery that included Lebanese mystic Kahlil Gibran and was a long-time patron of Irish poet W. B. Yeats and members of the Yeats family. Ford’s interest in the Yeats family stemmed from her love for the arts and literature combined with her Irish nationalist sentiments and played an important role in advancing Irish culture in America. Her philanthropic efforts leaned heavily towards literature, patronizing the Yeats sisters’ women-run printing business in Ireland, Dun Emer Press, but she was particularly interested in engaging young people in reading. She established the Julia Ellsworth Ford Foundation in 1934, which awarded an annual prize of $2,000 for the best young adult book (Fowler, 2019).

Inspired in all likelihood by her mother Julia, who was a painter, Ford encouraged artistic practice in her own family: two of her three children became painters, and Ford herself took up painting as a serious practice later in her life (New York Times, 15 August 1950). Julia used the hotel to house many notable guests, including the Yeats family when they came to America, and like her brother Samuel, used the hotel as a place to share works of art collected.

She showed kindness and generosity towards her staff with one particularly newsworthy case bringing her relationship with her staff to the public. Frances O’Shaughnessy was young when she moved from County Louth in Ireland to New York, following her husband George. Upon discovering her husband had been having an affair the whole time and planned to divorce her once she arrived in New York she became overwhelmed with anger. While employed by the Fords, she went by 43 West 74th Street to retrieve her book but instead went into Mr. Ford’s study and took his revolver. The then-pregnant O’Shaughnessy went home to confront George and when her pleas went unheard she shot him twice, and “prayed she would not miss”, on the night of May 5, 1911 (New York Times, Nov. 25, 1911, p. 22).

This sensational story was plastered all over the newspapers in New York with updates from the court, a real hot topic. Mrs. Ford was heard giving testimony in support of her employee, stating she was a “kindly, intelligent woman” (New York Times, Nov. 24, 1911, p. 4). O’Shaughnessy sent a letter to Mrs. Ford, she apologized for taking the revolver and hoped they would keep in touch. Indeed, they did. After she was acquitted on account of insanity, she moved out of the city and the Fords vowed to take care of her and keep her new life a secret (The Sun, Feb. 22, 1912, p. 4).

While employed by the Fords, she went by 43 West 74th Street to retrieve her book but instead went into Mr. Ford’s study and took his revolver.

Julia sold 43 West 74th shortly after her husband’s death. The next owner, Gustave Rubenstein, a pearl merchant, moved his family in. Around the 1950s, the rowhouse was converted into fifteen apartments. The majority of tenants were single working people, most notably from Central Europe and South America. Anne Bollinger lived in 5A. She was a long-standing Opera singer with the Metropolitan Opera nearby. She made her debut in a production of Carmen in 1949 and performed there until 1953 (New York Times, July 17, 1962, p. 25).

Today, the townhouse is undergoing extensive renovations by a new owner to restore many of the original facade elements and is returning to a private single-family dwelling. The original row has changed a lot over the years, however, 43 is determined to return back to its former glory, stoop and all.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!