370 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

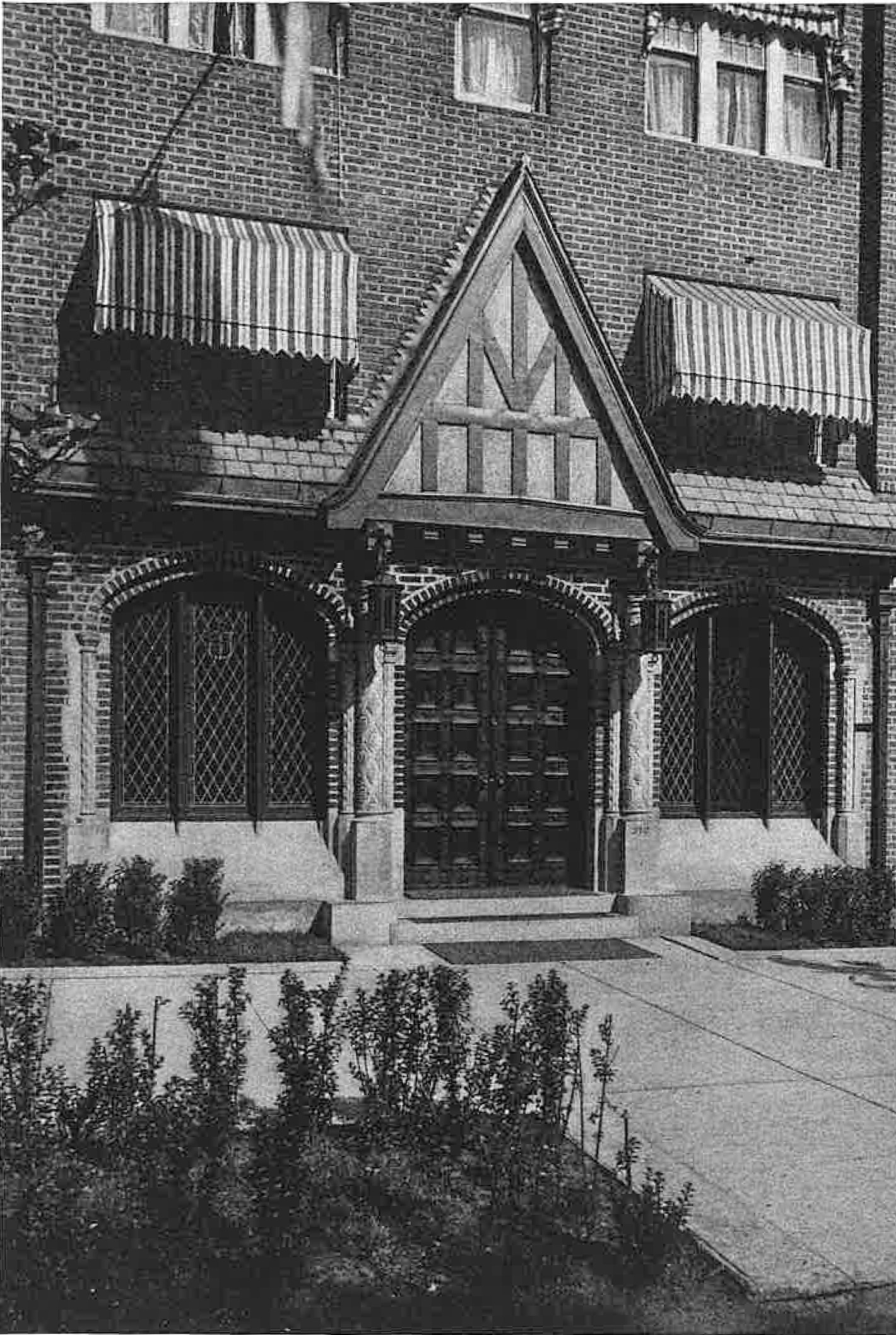

Fred Fillmore French founded the Fred F. French Company in 1910 when he was just 27 years old. At the time, the firm consisted of himself and a boy whom he paid $15 a week. He succeeded in the real estate business. In 1917, just seven years after starting out, he formed the 370 Central Park West Company and filed plans on March 17 for a “six-story elevator apartment” on the southwest corner of Central Park West and 97th Street. The property cost $150,000, and construction would add another $300,000, bringing the total outlay for the project to about $10.3 million in 2023 terms.

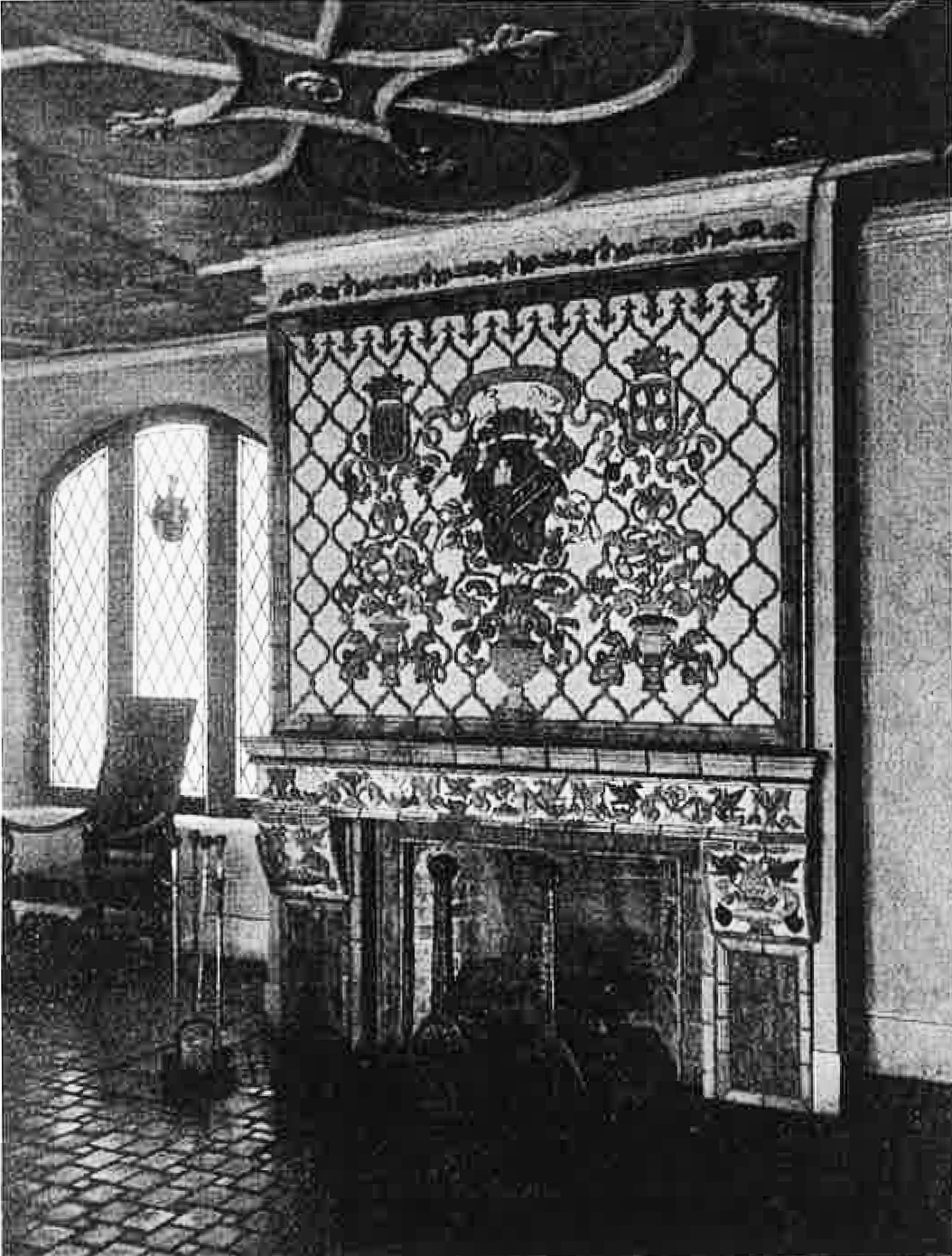

The Fred F. French Company’s architects designed a charming and romantic whimsy that foretold the neo-Tudor craze that would sweep the nation in the coming decade. By inserting deep light courts along 97th Street, they created the feel of a Shakespearean village on a modern scale. The six stories of “common brick,” were enhanced with Tudor half-timbering, sections of rough plaster, and a mountainscape of gables.

The Fred F. French Company wasted no time in marketing the project. An advertisement in The New York Times on July 24, 1917 read:

The apartment house unique, now under construction, S.W. corner 97th St. An old fashioned touch to a new fashioned home. Suites 2 to 7 rooms $650 to $1800. French Management Corporation.

The highest-end rent would equal $1,900 per month in today’s money.

Construction was completed within seven months. Some of the earliest tenants were affected by the war raging in Europe. On October 6, U.S. Navy ensign Donald Stewart Tuttle married Eleanor Church Gould in Lyons Falls, New York, while on a four-day furlough from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Sun mentioned, “The young couple started by automobile for New York, where they will be at home after November 1 at 370 Central Park West.”

The Fred F. French Company’s architects designed a charming and romantic whimsy that foretold the neo-Tudor craze that would sweep the nation in the coming decade.

Shortly after Helen Windsor Wilson, the widow of David H. Wilson, moved into 370 Central Park West with her son, Stafford Clay, the 25-year-old man was deployed to the battlefront with the 107th Infantry. Tragically, Stafford Clay Wilson was killed in battle near Peronne, France, on September 29, 1918.

One of the most colorful residents of 370 Central Park West was Maud L. Ceballos, an actress whose stage name was Maud Desmond, “the Dresden China Doll.” She had had a remarkable past. In 1903, she was taken to police headquarters from a Chicago club following a shooting. There, she and her escort gave fictitious names. The following year, she eloped with J. Reed Fuller, a Chicago businessman. The Sun remarked, “His disappearance after their marriage caused considerable comment.” That “disappearance” resulted in divorce. A year later, she was named in the divorce suit of Edna May and Fred Titus.

In August 1910, Maud sued Clifford R. Hendrix for breach of promise. She alleged, “he had for three or four years kept on promising to marry me as soon as I got a divorce from my first husband, Mr. Fuller.” She lost that suit.

She later married her dancing partner, Larry Ceballos. Shortly after their divorce in August 1919, she moved into an apartment at 370 Central Park West. Her name was back in the newspapers on May 8, 1920, when she once again sued Clifford R. Hendrix—this time on his wedding day. Her $100,000 suit accused him of a second breach of promise. Maud said he had paid for her divorce and further alleged he had promised to marry her on August 16, 1919. At the time, she said, he was in the process of building a house for them in Larchmont, New York. When Hendrix’s bride, Eugenia Terry, received word of the filing, she scoffed, “Some women seem to think they have a lien on men who take them out to tea.”

Hendrix told a reporter, “I never promised to marry Miss Ceballos nor did I ever entertain the idea of so doing. I knew her in my bachelor days, that is all. She has been married and has been freed.”

While she was at it, Maud sued her broker, Frederick B. Florian, on December 7, 1921. She claimed she had given him “between $6,000 and $7,000 to invest for her,” according to the New York Herald, “and could not get him to return the money.”

Maud’s case against Clifford R. Hendrix began on October 31, 1922. She was seriously grilled by the defense team about her history of lawsuits and love affairs. Two days later, the New-York Herald reported she had dropped the charges. Her attorney, James M. Fisk, explained that the cross-examination had made her so nervous that it was “physically impossible for her to go on with the case. She just cannot submit to any further examination,” he said.

Less controversial were the several artistic tenants in 370 Central Park West. In 1921, Frederic Warren’s apartment doubled as his studio, where he taught operatic voice. His advertisements offered “Full preparation for the concert and operatic stage.”

Among his neighbors was Helena Marsh, a contralto with the Metropolitan Opera Company. When she returned home from the theater just before midnight on September 26, 1921, she found her door open but barricaded from within. The New-York Tribune reported, “She called a policeman, who, with the aid of the elevator boy, forced the door in.” The burglar had escaped through a window. “Miss Marsh found her apartment in ruins, $400 in cash and about $5,000 worth of jewelry stolen,” said the article.

Living in what the New-York Tribune described as “an expensively furnished apartment” at the time was Jacques Roberto Cibrario, a “purchasing agent in America for the Russian Soviet government of motion picture machinery and films.” He was given the job of purchasing American-made films and film-making equipment in 1919 by the Soviet Department of Public Information. The materials were to be used “in making pictures for the education of the peasants in Communistic doctrine.” The New-York Tribune explained, “the Soviet rulers had been much handicapped by inability to reach the peasantry through ordinary educational propaganda, since only a small proportion of the public could read.”

When she returned home from the theater just before midnight on September 26, 1921, she found her door open but barricaded from within.

But now, in America and with a fortune in the National City Bank supplied by the Soviet Government, Cibrario seems to have been enjoying the capitalistic lifestyle. On September 1, 1921, he was indicted on four counts of grand larceny “in connection with the swindling of a good part of $1,000,000 advanced by the Soviets to him for the purchase of motion picture apparatus and films,” said the New York Herald.

The building continued to attract musical and artistic types. In 1926 Herman Neuman had his studio here. The wide-ranging musician advertised “accompanist, vocal coach, piano,” and “Musical Director Radio WNYC.”

Operatic and concert tenor and conductor John Hand lived here in 1931 with his wife, the former Ruth Worman. That year, he founded the New York Light Opera Guild to introduce young singers to the press and public. The Hands’ apartment now doubled as the Guild’s administrative office and de facto audition hall. On June 24, 1933, The New York Sun explained, “This is an educational and cultural institution for the advancement of American singers, and the stranger in New York, looking for an outlet for his talents, could find no better.”

Nine years later, on April 16, 1942, the Kingston Daily Freeman announced that the New York Light Opera Guild would stage Fatinitz early that June. The article noted, “Preliminary hearings are now being conducted at headquarters, 370 Central Park West, where applications for auditions should be made.” John Hand and his wife were still living here on October 11, 1956, when the 70-year-old suffered a fatal heart attack.

Professor of Economics at Columbia University Arthur F. Burns and his wife lived here in the 1950s. Born in Stanislau, Austria, in 1904, he graduated from Columbia University in 1925 and received his Ph.D. there in 1934. He had added to his responsibilities in 1945 when he became research director of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

While many of the low-rise buildings along Central Park West were replaced in the 20th century by soaring apartments, Fred F. French’s picturesque 370 Central Park West survived unscathed, a charming touch of old England among its Art Deco neighbors.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE