354 & 355 Central Park West

by Tom Miller

While magnificent palaces facing Central Park rose along Fifth Avenue in the 1880s, Central Park West sat mostly undeveloped. The problem was that landholders, sensing that the park-front lots would be highly desirable, priced them out of reach. Somewhat unexpectedly, Riverside Drive became the West Side’s mansion thoroughfare, instead.

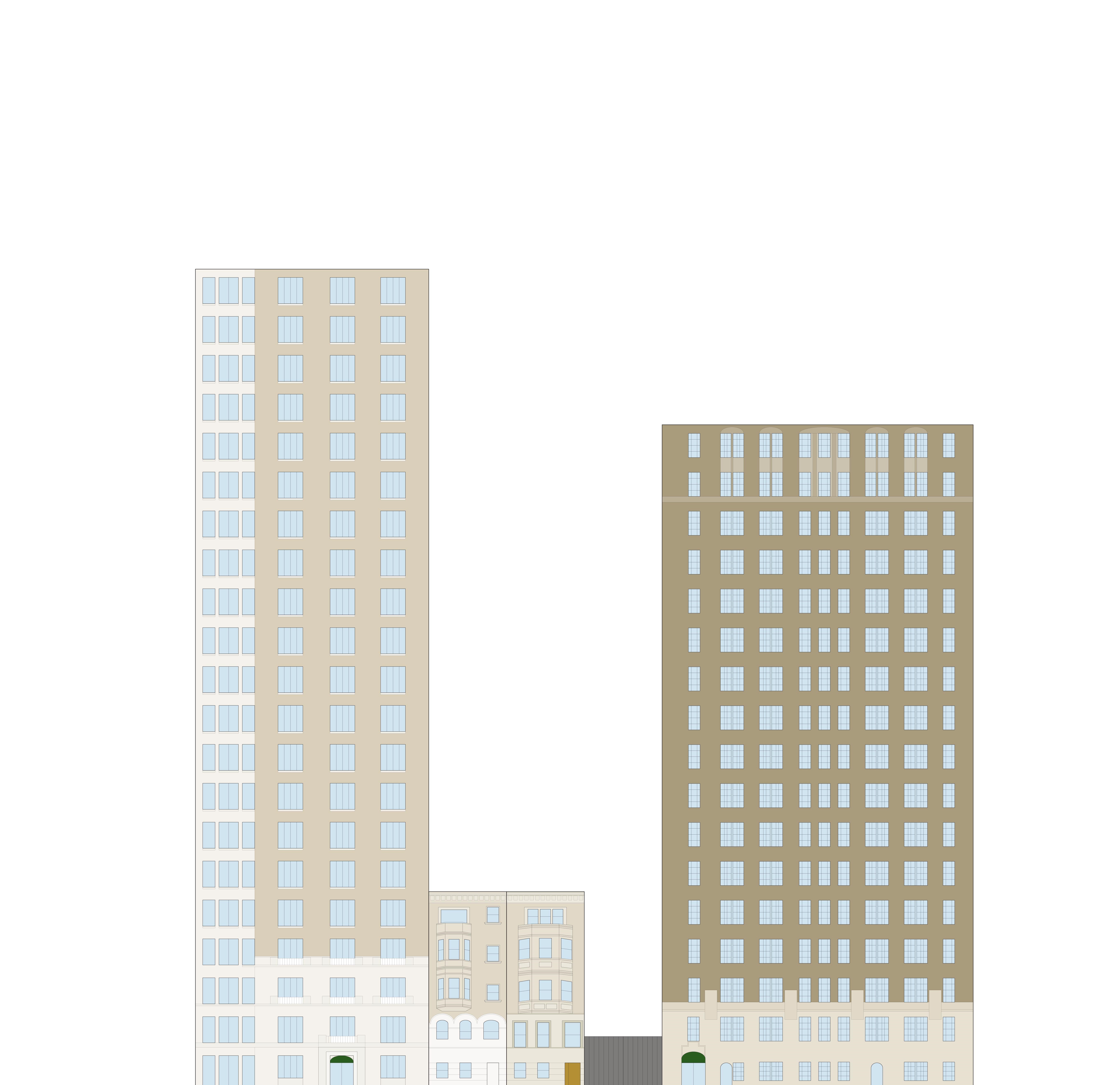

Along Central Park West first the Dakota, and then other scattered multi-family buildings were erected. They sat in a half-built landscape of board fences and overgrown lots. But in 1892 developer-builder Edward Kilpatrick made an exception by laying plans for five private homes—Nos. 351 to 355 Central Park West at the northwest corner of 95th Street.

Kilpatrick commissioned Gilbert A. Schellenger to design the row. Like the other architects busy on the Upper West Side at the time, he turned to historic styles, which he then liberally splashed with his own modern touches. The resulting merchant-class homes, completed in 1893, were generally Renaissance-inspired. The corner house, No. 351, stood out, being a story taller than the other four and grander with its impressive 95th Street entrance.

Nos. 352 through 355 were nearly identical, designed in an A-B, A-B pattern. Each was accessed by a shallow stoop, about four steps tall, and featured a two-story faceted oriel. Schellenger drifted into Romanesque Revival in Nos. 352 and 354 with arched parlor openings and medieval-style carvings below the bays. Faced in beige Roman brick and trimmed in brownstone, the residences were light and cheery compared to the dark brownstone fronts of the previous generation.

Brothers Julius P. and James C. Cahen were among Kilpatrick’s first buyers. The brothers were in business together, partners in J. P. Cahen and Brother. Although their father, Dr. Salmon P. Cahen was a highly respected physician and an officer in the West-Side German Dispensary; they opted for the silk trade.

On April 5, 1894, The New York Times reported that James C. Cahen had purchased No. 354 for $25,000 and that Julius had purchased No. 355 for the same price. The newspaper may have simply gotten the address wrong; but Julius bought and moved into No. 353, on the south side of James, instead. The brothers each paid the equivalent of $680,000 in today’s dollars.

Purchasing No. 355, instead, was William F. Carroll and his wife, Catherine. The title was transferred to Catherine C. Carroll on June 4 that year. Carroll was active in real estate on the Upper West Side and it is unclear whether the couple lived in the house; or merely leased it.

The boys realized at some point that they had a “secret passage” between their homes…The two best friends would use the route in laying their plans for a Tom Sawyer-worthy exploit.

In either case, the families in Nos. 354 and 355 Central Park West lived respectable and quiet lives in their 10-room homes. Julius Cahen became secretary of the Board of Trustees of the West-Side German Dispensary (James was its president). His wife focused her attentions on the New York City Mothers’ Club, rising to President in the first years of the new century. The goals of the organization were “to promote the education of women in the wise care of children and to uplift and improve the condition of mothers in all ranks of life.”

The New-York Tribune ran a weekly column entitled “Things to Think About,” which presented readers riddles and puzzles to solve. Those who sent in the solution would be rewarded with their names printed in the newspaper and their choice of a small prize. One puzzle was related to “Little Men and Little Women.” It was apparently a favorite pastime in the Cahen household.

On June 11, 1905, 14-year old Harold A. Cahen won the prize for the previous week. His little sister, Edith, who was five years younger, would get her share of the spotlight three years later. On May 24, the Tribune reported “The neatest and best three answers were contributed by Edith R. Cahen, aged twelve years.” It seems Edith was thinking of her brother when she chose her prize. The newspaper noted that she “wishes a boy’s Tribune watch.”

By now, the Carrolls were definitely leasing the house next door. Despite an announcement in the New-York Tribune on June 4, 1902, that William had sold No. 355 to L. M. Aldrich; the deal was never completed. In 1904, the house was being leased by Gerald Brooks, the son of Belvidere Brooks, general superintendent of the Western Union Telegraph Company; and by 1907 to newspaper broker William H. Gutelius.

Gutelius and his wife had two sons, William and Sylvester (known fondly as Buster). The virtuous William left home in February 1907 for missionary work in China. The younger Buster had adventures of his own in mind at the time.

Buster, 16 years old, was a student in the Preparatory Department of the College of the City of New York. His best friend was John McWilliams Wylie, the 15-year old son of the pastor of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, next door to the Gutelius house. The boys realized at some point that they had a “secret passage” between their homes. An iron cover in the wall below No. 355 opened into the basement of the Scotch Presbyterian Chapel. “From the chapel the passage led to the church basement, and from there up into the back yard of the rectory,” explained The New York Times later. The two best friends would use the route in laying their plans for a Tom Sawyer-worthy exploit.

In April, items began missing from both households. The cook in the Wylie house could not find her iron cake turner. A brand new candlestick, tin plates and cups, candles and matches were suddenly gone. And a broom from the Gutelius kitchen went missing. Then on April 26, both boys disappeared as well.

After they had loaded up a crate of supplies, they realized it was too heavy to carry from the Wylie back yard. They tried to convince an express man to help, but he refused. So they were forced to leave it behind. Carrying their suitcases and using the $25, they each obtained by selling their bicycles, they boarded a train for Port Jervis, New York.

Their dreams of roughing it in the mountains seemed to be coming impossibly true when they found an abandoned farmhouse just over the Pennsylvania border. Young Wylie later said “We bought an axe from Mr. Maloney, the storekeeper and postmaster [in Mill River, Pennsylvania], and we asked him what was good for us to cook. He told us flapjacks and eggs and salt pork made good rations, and Mrs. Maloney, his wife, showed us how to cook.”

They had explained to the couple that they were students in a private school in New York and “were in search of some needed outdoor recreation.” They had money and one boy carried a rifle, so everything seemed in order to the Maloneys. Mrs. Maloney gave them some blankets for the cold nights and J. F. Maloney loaned them an old “sheet iron stove.”

Living in the old farmhouse was too civilized for the adventurers, and after a few days, they moved into a “nice, warm, dry cave.” They tried catching fish, and spent much time cutting firewood and honing their culinary skills. They happened on a stone quarry where the boss told them he would hire them when they ran out of money. “Breaking rocks is first class exercise,” he told the boys.

But the runaway teens’ hopes would soon be dashed. When they had failed to come home from school that Friday afternoon, their parents had reported them missing. By Tuesday the New York, newspapers reached the Mill Rift Post Office. Postmaster Maloney became suspicious. When Wylie and Gutelius returned, he compared their faces with the photographs. Rather than confronting them and risking scaring them away, he quietly mailed off a letter to Rev. David G. Wylie. On the morning of May 3, Dr. Wylie and his other son arrived at the post office while the Gutelius family waited nervously on Central Park West for word.

Maloney sent a neighbor, Samuel Wilson, to the mountain cave with word that the postmaster needed to see him. Leaving Buster cooking bacon and flapjacks, he rushed to the town. When he entered Maloney’s store, he was confronted with his father and brother. The quixotic adventure was over.

Buster Guletius was sent for, and The New York Times reported, “When he learned what had happened he promptly ‘threw up the sponge,’ but it required a great deal of persuasion to induce him to return to New York with the Wylies.” Before he would do so, he insisted that the entire party have dinner with them in the cave. They accepted.

The Times wrote, “Dr. Wylie was much impressed by the natural habitation, and was delighted to find that the boys had been living in a comfortable manner. However, they had but $2 left.”

Their surprising financial success during the difficult economic times was made clear when the FBI raided the store on July 3, 1936.

The following morning the New-York Tribune ran a headline reading “Cave Boys Come Home.” The newspaper advised, “The erstwhile cave men, or cave boys, did not willingly leave their subterranean retreat in a mountainside near Millville, Penn., but they came back at the earnest persuasion of Dr. Wylie.”

The Guletius family left No. 355 within the year. William and Catherine Carroll continued to lease the house to a series of renters. In 1912, Thomas Minal moved in; and in 1915, Charles Bloeh signed a lease. By now, the Carrolls were living in Colorado Springs.

By 1920, the Cahen family had left Central Park West. The family of Frank Lowenfels now called No. 354 home. Lowenfel was an executive with Julius Schmoll & Co., “dealers in hides,” at No. 150 Nassau Street. Working in the Lowenfel household seems to have been a challenge; for Mrs. Lowenfel was continuously looking for a maid.

On April 22, 1920 she placed an advertisement for a “chambermaid, waitress,” noting clearly that the family had “no children.” The following year, in September, she placed another ad. This one pointed out that she was looking only for a “white girl.” Seven months later, she was looking again.

On January 27, 1928 The New York Times announced that Morris Rothschild intended to erect two apartment buildings—one “on the church property, which comprises the south corner of Central Park West and Ninety-sixth Street, and the other “surrounding the north corner of Ninety-fifth Street and Central Park West.” Nos. 354 and 355 Central Park West would have seem doomed had the article not mentioned that Rothschild had purchased No. 354 “to protect the light of the new building” on the north corner and to preserve “the view of the park for all the apartments facing south and east.”

While Rothschild’s projects wiped out three of Edward Kilpatrick’s row, they ensured the survival of Nos. 354 and 355.

The following year both houses lost their porches. The Board of Transportation noted in 1929 that both buildings “had stoops and porches which projected over the sidewalk. In order to construct the subway and the sewer which came under these porches the Contractor removed them. The Borough President ordered the removal of all encroachments along Central Park West and counsel advised that these porches be not restored.” Eminent apartment building architect Rosario Candela was hired to make the necessary renovations.

No. 355 was sold at auction to Catherine F. Mitchell for $29,750 on September 11, 1931. Two years later, it was leased to the Florsheim Corporation, which announced it “will be altered to rent as one and two room apartments.”

The former Cahen house next door remained a single-family home for decades. In 1936, it was home to John W. Kelly and his family. He and his wife, the former Evelyn Armstrong, had three grown children, John R., Evelyn and Edith; all married and living elsewhere.

John and his brother Gerald ran a jewelry store in the first floor of a tenement building at No, 791 Amsterdam Avenue during the Depression years. In business with them were their sons, John R. Kelley and Gerald Kelly Jr. Their surprising financial success during the difficult economic times was made clear when the FBI raided the store on July 3, 1936. The Kellys were less in the jewelry business than in distributing Irish Sweepstakes tickets—an illegal operation in the United States.

The New York Times reported that authorities “believed the raids had smashed the largest distribution headquarters in the United States for the Irish Free State Hospitals sweepstakes.” All four of the Kellys were arrested in what the FBI called “an ostensible jewelry store.” The agents told reporters that the shop “served merely as a blind for the widespread operations which were conducted in a suite of old living quarters behind it.”

They Federal agents then visited No. 354. The Times reported “The Central Park West address, according to the police, served as the executive and managerial headquarters for the ring, where orders were received and the business correspondence transacted.”

Despite his run-in with the law, John W. Kelly remained in the house. Now widowed, he was still living here when he died on December 12, 1957. The house remained a private home until 1968 when it was converted to one apartment on each floor.

No. 355, too, contained only four apartments until 2009. That year it was reconverted to a single family home. The last survivors of the 1893 row have changed little since they lost their porches in 1929. Unusual as private homes on a thoroughfare of apartment buildings nearly 125 years ago; they are delightfully even more out of context today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

Landmarks Timeline

BUILDING DATABASE

354 Designation Report

355 Designation Report